SANTIAGO/LIMA, (Reuters) – A decades-old maritime dispute between Chile and Peru goes to a final ruling next week with both governments hoping it will end one of Latin America’s last big border spats and improve ties between the two trading partners and longtime rivals.

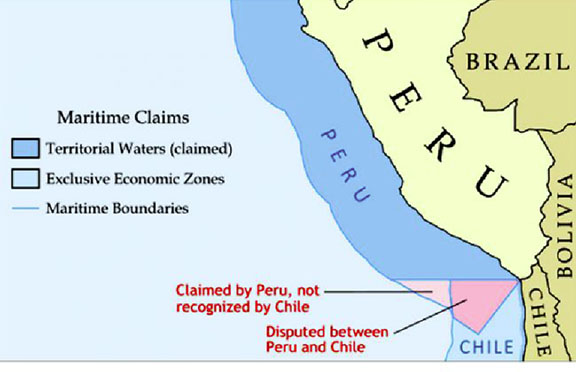

On Monday, the International Court of Justice in the Hague will rule on Peru’s claim over 38,000 square kilometers of Pacific Ocean that Chile controls, as well as a claim over a slice of international waters.

On Monday, the International Court of Justice in the Hague will rule on Peru’s claim over 38,000 square kilometers of Pacific Ocean that Chile controls, as well as a claim over a slice of international waters.

The ruling could lead to a temporary flare-up in nationalist rhetoric but both governments have promised to abide by it, and in the long term the ruling should draw a line under an issue that has been an irritant to relations between the Andean neighbors.

“With the Hague ruling we’ll define our maritime border with Chile, and then all of Peru’s terrestrial and maritime borders will be sealed forever,” said Jose Garcia Belaunde, who was Peruvian foreign affairs minister when the case was brought to the Hague, in the Netherlands. “It took us 200 years but we’re doing it.”

The case, which has been covered in-depth by domestic media on both sides of the border, dates back to the 1880s War of the Pacific, a struggle that ended with Chile winning territory from both Peru and Bolivia.

Resentment has simmered ever since, and Bolivia – which still keeps a navy despite being landlocked since that war – has also filed a claim against Chile in the Hague, demanding a land corridor that would give it access to the sea.

Peru argues that its maritime border with Chile has never been fixed. Chile points to treaties signed in the 1950s that it says set the boundary where it lies today.

TRADE IS THE MORE VALUABLE ISSUE

Fishing in the disputed area controlled by Chile is estimated by a Peruvian industry body to be worth around $200 million a year, mainly anchovy used for fish meal and oil.

The rich fishing waters largely lie within 10 miles of the coast, so any territory awarded outside of this zone would have less immediate value.

But the value of the marine resources at stake is a drop in the ocean compared with trade between two of Latin America’s most dynamic economies. Neither government wants to jeopardize growing investments that each country has in its neighbour.

Bilateral trade is now worth over $3 billion a year after rising nearly five-fold between 2002 and 2012, according to Peruvian customs data. Chile has around $12 billion in investments in Peru and is Peru’s biggest trade partner in Latin America. Significant numbers of Peruvians live in more affluent Chile, with the remittances they send home an important source of regional income.

“This is an important step because it consolidates our relationship,” Peruvian Finance Minister Luis Miguel Castilla said on local broadcaster RPP.

“There will be a much stronger country-to-country effort.” Both countries are members of the Pacific Alliance, a nascent trade bloc of investor-friendly nations that outgoing Chilean President Sebastian Pinera has done much to promote over his four years in office.

His government would defend Chile’s interests, he said on Monday after he convened the National Security Council to discuss the upcoming judgment. But it would also work to “ensure continued collaboration that is in the interests of both countries,” he added.

A CALL TO RAISE FLAGS IN PERU

Popular reaction, whipped up by years of pointed history lessons and jingoistic media coverage, could be much more heated. Political leaders will need to steer a careful course in the wake of the verdict, analysts caution.

“They’ve done the best they can to mitigate any consequences of the decision, but it’s always hard to predict how these things pan out,” said Michael Shifter, head of the Inter-American Dialogue think tank. “It’s going to be a test for the leadership in both countries on how they manage this.”

In March, Pinera will be replaced by left-leaning Michelle Bachelet, who was president in 2008 when the case was brought. She has said little in recent weeks but is known to attach less importance to the Pacific Alliance than Pinera.

It will be her government that will have to deal with implementing the decision, which could take years to put into practice and could be fractious, particularly if it impacts on jobs in the border area.

Peruvian President Ollanta Humala, whose low approval ratings could be boosted by a favourable verdict, has tried not to stoke tensions.

But his loudest critic and likely candidate for the presidency in 2016, ex-leader Alan Garcia, has been swift to pin his own colours to the mast, with proposals to raise flags throughout Peru and encourage employers to show the Hague broadcast live or let workers come in late.

There has been no indication of the direction of the court’s decision on Monday, although some sort of compromise is likely.

For Peru, a legal victory would assuage old humiliations, Peruvian international relations analyst Farid Kahhat said. “In terms of territory Peru has nothing to lose,” he said. “The only defeat that Peru can suffer is to its collective self-esteem by losing to Chile again.”