By Amos Sarrouy

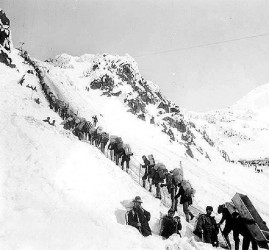

When gold was discovered in the Klondike in North Western Canada in the late 1800s, more than 1,000 people rushed to the area. When ships carrying gold first arrived in the United States, that too sparked a fever. Americans stampeded to the Klondike hoping to get rich. To prevent starvation among the reckless gold seekers the Canadian authorities refused to allow anyone in unless they had a year’s supply of food. Between the weight of supplies and all their equipment, many of the prospectors had to move their baggage in stages, carrying around 29 kg at a time. Some of them had to make the 30-mile trip over the mountains and down the Klondike River more than 30 times.

In less than a year Dawson city exploded from 500 people to over 30,000. In the winter the temperature often dropped below -50°C. The summers were dry and hot and prospectors, diggers with shovels and picks, had to deal with shortages, wild animals, and thieves. Of the more than 100,000 who travelled to the Klondike hoping to make their fortune, many died, many lost everything, and only a few hundred became rich. But gold is a magic word and danger disappears when people hear it.

That was the golden age of prospecting in Canada. Gold mining is very different today. The vast majority of mines are operated by multinational corporations like Barrick Gold and Goldcorp. Their mines run on an industrial scale, employing thousands of workers and expensive equipment to extract tons of gold. Prospecting is still practiced in Canada, but it is more of a hobby than a career. In the days of the gold rush, a prospector only needed to stake a claim before he could start mining. Today, Canadian prospectors need to obtain permits and read and follow pages of regulations relating to everything from mining methods to whether or not they can fish in an area. Staking a claim takes time and mining requires expensive equipment.

Guyana’s connection to gold goes back many years. The first book ever written about Guyana was The Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empyre of Guiana (With a Relation of the Great and Golden Citie of Manoa (Which the Spanyards call El Dorado) and of the Provinces of Emeria, Aromaia, Amapaia, and Other Countries, with Their Riulers, Adjoyning by Sir Walter Raleigh. El Dorado was the legendary city of gold and mentioning it in the title of the book was meant to entice people to this region.

It’s no surprise that gold mining is one of Guyana’s biggest industries in the country today. It has been sustained by a tradition of prospectors known in this part of the world as pork knockers, even though, these days, they use backhoes more often than picks. Like the prospectors of the Klondike, pork knockers face difficulties that have more to do with their remote and difficult work environment than with government regulations. Mines tend to be deep in the interior and transporting workers and equipment is difficult and dangerous. They face threats from supply shortages, disease, wildlife and thieves. Work is hard and time off is tedious. The industry is also largely unregulated. To stake a claim a miner must register it with the Guyana Geology & Mines Commission (GGMC). A source in GGMC said, half-jokingly, that Guyana is so large and its population so small that even if the entire population of Guyana were hired as mining inspectors there still wouldn’t be enough to police all of the mines in the country.

Environmental and safety inspections must be carried out and contracts must be agreed upon by the company, the government and any affected Amerindian villages, all of which can take years. It takes so long, in fact, that it’s fairly common for companies to discover that pork knockers have staked several claims in areas they wanted to mine while they were waiting for approval.

There are several benefits multinational corporations bring to Guyana. They employ a lot more Guyanese than the smaller local mining companies. They also collect gold and other resources much more thoroughly from each area, and because a company is a single entity operating only a few mines, it is much easier for inspectors to enforce regulations.

The local, smaller mining operations exist in much greater numbers. The GGMC maintains a map online of all the medium and large mining properties currently on file, which is updated every month. It isn’t linked to anywhere on their website, but can be found by following the link at the end of this article. Large multinational properties are marked in green. Grey mines are medium sized and are either locally or foreign owned. The smallest claims are simply too numerous to be marked. There are an estimated 15,000 mining claims in Guyana and they are all filed as a set of directions to the claim rather than points on a map.

The pressure on the smaller miners is growing. Advances in satellite and computer technology, for example, are making it easier to identify legal and illegal mines and mark their GPS coordinates for police and inspectors to track down.

There are also international forces promoting protection of the environment and stopping climate change. For example, the Guyana REDD+ Investment Fund (GRIF) includes a deal in which Norway has agreed to pay up to US$250 million to Guyana if it is able to avoid deforestation following certain benchmarks. This makes protecting the forest from mining activities another expensive priority for Guyana’s government.