The Link Show is celebrating its 30th production during its current run for the year 2014. This annual satirical revue directed by Ron Robinson and produced by Gem Madhoo-Nascimento may be considered a major achievement for many reasons. It was founded in 1981 by The Theatre Company and continues now as a joint production of that company with GEMS Theatre Productions.

It has survived (and has been reinvigorated) with the same leading personalities who started both the Link Show and The Theatre Company – Robinson and Madhoo, with Ian McDonald at that time as the third member of the directorate. McDonald, a leading Guyanese poet, wrote the lyrics for the show’s theme song ‘Stand Up Stand Up and Say It Is So.’ Mrs Madhoo-Nascimento has emerged as the most proficient theatre and production manager in Guyana, while Robinson is the foremost and most decorated director and actor.

A satirical revue like the Link Show was not entirely their invention. They revised a tradition carried on by The Theatre Guild through the 1970s, mainly led by outstanding national dramatist Frank Pilgrim, which was then known as The Brink. Robinson, once Chairman of the Guild, moved with Gem Madhoo (also a Guild member) to form a new private company, launching it with their version of the Brink. As a radio news anchor, he drew on two sources – the popular GBC radio news ‘Link’ and the Theatre Guild’s ‘Brink’ – to create the name for the first Link Show. In so doing they contributed to the development of the commercial theatre in Guyana, with regular performances at the National Cultural Centre. This new venue transformed the Guyanese stage, collaborating in the rise of theatre as a profession and the significant popularisation of drama. It began playing to a much larger audience and a popular, more proletarian audience. This move also saw the rise of popular plays, thrillers, and a succession of new local Guyanese plays.

![]() Within this, the Link Show established itself as a tradition and as the most popular production on the local stage attracting the largest audiences. This was an achievement. But perhaps greater than that is the place it now holds in the wider Caribbean context. The Brink did not invent its kind of theatre either. It was a version of annual satirical year-end revues already performed in the region – notably Jamaica where there were Eight O’Clock Jamaica Time and Rahtid! Barbados also had Bimshire. This was an important part of the great satirical tradition in Caribbean theatre and traditional performance culture.

Within this, the Link Show established itself as a tradition and as the most popular production on the local stage attracting the largest audiences. This was an achievement. But perhaps greater than that is the place it now holds in the wider Caribbean context. The Brink did not invent its kind of theatre either. It was a version of annual satirical year-end revues already performed in the region – notably Jamaica where there were Eight O’Clock Jamaica Time and Rahtid! Barbados also had Bimshire. This was an important part of the great satirical tradition in Caribbean theatre and traditional performance culture.

What makes The Link Show such an achievement in this context is its survival. After 32 years it now stands out as a standard bearer for this brand of performance. It takes a prominent place in a long and noble Caribbean theatre tradition. None of the three named above from Jamaica and Barbados survived; neither have a number of others. The Link is now only superseded by the Jamaica Pantomime Musical which is by far the oldest and most established in the region. The Link also stands beside the annual political satire of Laff It Off set up in Barbados by Thom Cross.

Guyana’s comedy show is also meritorious for its elevation to the good quality that it now sustains. It faltered for many years in standards and integrity before learning to be properly satirical in content and typology. It is one thing to be comic – to be able to depict popular jokes on stage, but the art of satire demands more than common humour or slapstick. The Link was inconsistent and often failed to achieve this for a long period before settling down and exhibiting that it knew the difference between farce and satire. At the same time it climbed the ladder of competence to very good professional levels, with repeated excellent performances.

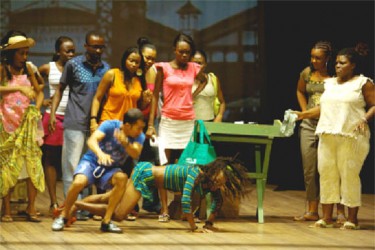

Link Show 30 demonstrates that it has managed to take with it on this elevation, a team of actors that understand the style and the demands of this type and this level of professional performance. There is now a team at work on stage led by a sound, confident director. The management of the stage business, the design and the production is efficient and effective. Link Show 30 is a disciplined professional production with intelligent acting.

Another significant factor is that for the second time in history, the Link is opening up a new performance venue. Thirty years ago it was the Cultural Centre that at that time was not the primary venue for theatre. But little by little producers were executing a shift from the Theatre Guild Playhouse in order to open up the local commercial theatre in which plays were done for payment. Concurrent with that was the admission of a much larger popular audience. In 2014 the producers departed from the stage on which they had performed 29 previous shows because of the breakdown of air conditioning, light and sound at the NCC, and performed number 30 at Parc Rayne, a newly fashioned playhouse at Rahaman’s Park with the assistance of Ray Rahaman.

One telling irony is that this shift carried with it some change in audience. There was a definite falling off in the multitudes of working class theatre-goers and the house was made up predominantly of the middle class. This was the direct opposite of what happened when the move was made from the Theatre Guild to the Cultural Centre three decades ago.

However, it was a very interesting change theatrically. Apart from social class, there were adjustments in technical theatre which the production handled in very instructive fashion. First, refashioning a building into a small theatre auditorium for 400-500 seating moved Guyanese theatre a bit closer to the Jamaica experience. Following the historic creation of the Barn Theatre by Trevor Rhone and Yvonne Jones-Brewster in 1970, Jamaica is fully accustomed to a variety of spaces converted into small theatres seating much less than 400. The style and shape of Jamaican theatre has thrived on that, particularly in the New Kingston area.

At least Parc Rayne is not dependent on air conditioning or a powerful sound system because of its contrast in size to the vacuous acreage of the NCC, but it certainly missed creative and focused lighting. It had to depend on an on-off manual system. But the production adapted well to the greater intimacy and the much smaller stage. To their distinct credit, they took to it with crisp efficiency and managed the scene changes with a newer, progressive style of theatre. The pace was brisk, the changes sharp and lengthy black-outs totally eliminated. It was a lesson in stage business very useful to local students of the art, with actors participating directly in set changes in the manner of the more avant-garde improv. The director, stage manager and actors had innovation forced upon them. It led to a taut, disciplined, ascetic and well organized production.

On the whole the satirical pieces were never less than good. There were fewer bad scripts although one or two would have better fitted in Stretched-Out Magazine – they were drawn out, leading to a weak punch-line. One of the popular regular features, ‘Over The Fence’, had moments, but for the most part lacked dynamic dramatisation. It preached repetitively, telling rather than showing, while other regular features thrived.

An excellent example of these was ‘Deolatchmee.’ Nirmala Narine has perfected this telephone conversation which has seen changes over many years since Richard Narine made it his own. There have since been different characters, but now the dramatic persona is an excellent satirical take-off with a believable personality. The market scene was the opposite of ‘Over The Fence’ with a series of bits of lampoon and commentary effectively dramatised.

While another creditable feature was the way choreographer Leslyn Fraser managed to get the whole cast to dance without jarring incapabilities, the show still had a problem using dance to make satirical comment. In some of the recent shows the musical pieces have been a let-down, but this time the songs were much better put together and performed. This improvement included the harmonious addition of Junior Calypso Queen 2014 Shauntell Gittens.

It might have been a good deal of hard work knocking Rahaman’s Park into shape to accommodate dramatic performance, but it certainly worked well for Link Show 30. They might have suffered at the box office because of the location and the smaller auditorium, but it was a rewarding experience artistically. Not only did the actors learn to work on different stage dimensions, but it might well have been an instructive adventure in the styles they had to adopt.

Additionally, Parc Rayne has shown reasonable possibilities for an alternative theatre venue. It did well for a makeshift stage and auditorium and one can find no better example of small theatre spaces like these than in the even smaller stages in Jamaica.