Last week’s column introduced six performance indicators for the sugar industry, which I will examine in coming weeks: production, costs, profitability, land productivity, factory productivity, and combined (land and factory) productivity, in that order. Today I will complete the first of these, which was started last week by considering estates and farmers production.

Last week’s column introduced six performance indicators for the sugar industry, which I will examine in coming weeks: production, costs, profitability, land productivity, factory productivity, and combined (land and factory) productivity, in that order. Today I will complete the first of these, which was started last week by considering estates and farmers production.

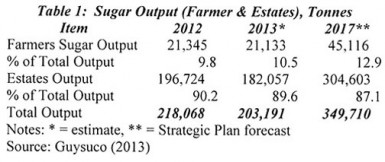

Table 1 provides production data for farmers and estates; 2012 shows actuals; 2013 shows estimates; and, 2017 shows forecasts provided in GuySuCo’s Strategic Plan. In 2012, farmers’ share of sugar output was 9.8 per cent; and this is forecast to rise to 12.9 per cent by 2017. Consequently, estates’ production accounted for 90.2 per cent in 2012 and is forecast to decline to 87.1 per cent by 2017.

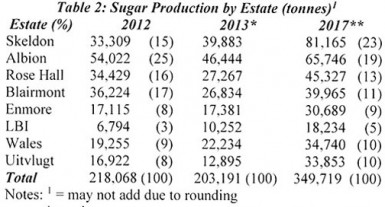

Table 2 shows this output by estate for 2012, 2013 and 2017. The leading estate in 2012 was Albion (25 per cent); followed by Blairmont (17 per cent); Rose Hall (16 per cent); and Skeldon (15 per cent). Combined, the Berbice estates produced 73 per cent of total output.

*= estimate

**= forecast

Source: GuySuCo 2013.

The Strategic Plan forecasts for 2017 indicate 1) the share of Berbice estates declining to about two-thirds of the total, while the Demerara estates rise to one-third; 2) the biggest change area is Skeldon where output is projected to rise nearly 2.5 times with its share of total output rising from 15 per cent to 23 per cent; 3) the output shares for Albion, Blairmont and Rose Hall fall, even though their totals rise; and 4) the relative positions of the lowest producing estates remain stable.

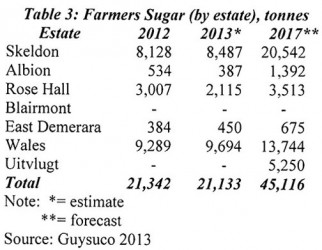

The distribution of farmers’ sugar by estate location provided in Table 3 shows the primary concentrations for 2012 were Wales (9,289 tonnes), Skeldon (8,128 tonnes) and Rose Hall (3,001 tonnes). The 2017 output is forecast to more than double for Skeldon (20,542 tonnes), and rise substantially for Wales (13,744 tonnes). Rose Hall’s output rises modestly to 3,513 tonnes. Farmers’ production on all the other estates remains small (around 3 per cent).

Targeted v actual output

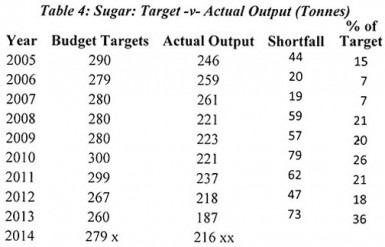

As the production debacle continues, one crucial aspect of it is manifested by comparing targets set in the annual national budgets to actual performance (See Table 4). The annual budget target is chosen because of the practice of spokespersons for the industry reducing yearly target levels as they come closer to the end of the year. This practice is intended to disguise industry underperformance.

Notes x = Strategic Plan Target

xx = Current Target applied (March)

Source: Government of Guyana Official Statistics, GuySuCo

Table 4 reveals that for each year since 2005 there has been a significant shortfall of actual output against targeted output; ranging from as high as 93 thousand tonnes (2013) to 19 and 20 thousand tonnes (2006 and 2007). For the full period, the total shortfall is 460 thousand tonnes (about one-fifth of targeted output).

The 2014 data indicate the current industry target (March 2014) juxtaposed to that provided in the Strategic Plan.

Propaganda, spin

One of the most tragic dynamics facing the industry is that those who are politically responsible for it (and indeed those who are responsible for managing it, but feel ‘obligated’ in some way to those who are politically responsible for it) readily resort to spin and propaganda in preference to facts. Spokespersons make outlandish claims, knowing full well they will not be challenged by industry insiders. Consider the follow six claims made by the Government Information Agency in February 2010 about the Ministry of Agriculture’s report to the Economic Services Committee of the National Assembly:

1) GuySuCo’s Strategic Blueprint for success has been producing positive results.

2) Production costs (including management and cane production costs) are falling.

3) Co-generation of electricity from Skeldon to Berbicians is turning out to be a salvation.

4) Skeldon now is offering a dramatic increase in factory capacity.

5) The industry’s break-even output level is 310,000 tonnes.

6) Guyana’s sugar would be profitable by 2012.

It amazes when such barefaced nonsense is uttered “officially” in the National Assembly, with little public outcry. The expectation then was that, by now, most readers would have forgotten these utterances. And, even someone as hardened as I am to the self-deception and ostrich-like behaviour which infect those who do not want to critically engage over the future of sugar, finds such “official” declaration beyond belief.

Next week I begin consideration of the second performance indicator: costs.