Competitive chess players are becoming increasingly aware of the calamitous nature of blunders, those irrefutable errors which occur when one least expects them. From the level of the elegant super-grandmasters way down to the lowly 1300 patzers, blunders continue to plague us without respite. Can we prevent them from happening? I do not think so. Obviously, ghastly blunders will not disappear because we wish them to do so, nor with the wave of a magic wand. Blunders in chess, as in life, are here to reside among us. However, it may be possible to control the frequency of one’s blunders.

Soviet grandmaster Alexander Kotov tells us in his incisive bestseller, Think like a Grandmaster “everything that happens by chance has some explanation, and there is some strange logic in the appearance of blunders.” A grandmaster tournament is a struggle between finely trained minds which are capable of carrying out excessive mental work for hours on end. A grandmaster, through extensive practice and training, gets used to making the deepest of analyses, thereby enabling him to foresee the course of events many moves ahead. Yet, simultaneously, there is not a single grandmaster who has not made the grossest of blunders in his time. He/she may have overlooked an elementary checkmate, or given up his roving queen or parted with an active minor piece. How can a trained mind suddenly exhibit a blind spot? It’s puzzling.

In chess one of the favourite explanations for blunders is ‘a lapse of concentration. Were you concentrating less when you made the blunder than you were during the previous stages of the game? Did you play your move in a trance? Or were you admiring an attractive woman?

The chances are you were engaged in the identical behaviour you were previously – you were thinking about the position. One popular chess analyst believes that blunders are committed following a period of quiet excitement or of self-satisfaction. Like when you are close to winning a game, or about to realize a strategy.

Another reason why blunders occur is seemingly insufficient knowledge of tactics. Many texts preach to us that nothing can compensate for a lack of tactical ability. Russia’s master trainer Mark Dvoretsky emphasizes the point in his book, Training for the Tournament Player. He recommends that chess players should solve tactical puzzles frequently to overcome the problem. Also, another cause for blunders is the failure to fully understand a position and its strategic components. The experts tell us that you should constantly try to penetrate the position at hand through strategic thinking, calculating, guessing the opponent’s intentions and keeping your mind clear and sharp. You can ask questions to yourself about the position, calculate some interesting variations, and do so while your opponent is pondering his next move. And at all times, beware of overlooking some basic component of a strategic position.

Chess literature on the subject of blunders is plentiful. A colleague once asked an intriguing question: suppose that chess did not exist, that it had never been invented? I think about that question, and one thing I know for certain is that we would have been severely disadvantaged in terms of refining our thinking processes had it not been for chess, the king of games and the game of kings.

A common thread runs through both chess and life when we fail to make clear plans; when we have inadequate knowledge of strategy and tactics; when we have a poor grasp of the current position; when we underestimate our opponent’s counter-attacks; when we become too obsessed with a single line of attack and become emotional because victory is in sight. Dr Alexander Alekhine believed it essential for every strong chess player to develop in himself “unwavering attention, which must isolate the player completely from the world around him.” Complacency and over-confidence have proven to be the demise of many a chess player, according to Alekhine.

In current chess news, Kasparov visited the gravesite of the incomparable Robert ‘Bobby’’ James Fischer last Sunday on his birthday in Iceland. Kasparov noted that it was a sad day for himself because the graveyard represented so many great hopes and unfulfilled expectations which were never realized. Fischer and Kasparov, arguably the finest chess players ever, had never met. Kasparov referred to Fischer as a “legend” and said that all that was left is this huge sadness now that he is gone.

The Candidates chess tournament to identify a challenger for world champion Magnus Carlsen has begun, and Vishy Anand has demolished the Armenian favourite to win the tournament, Levon Aronian, in the first round. The game is not yet available.

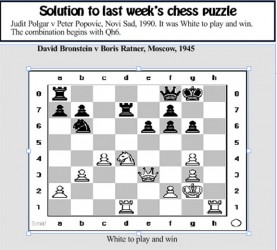

Chess game

One of the most famous blunders of all time was committed by world champion Tigran Petrosian against his rival David Bronstein at the 1956 Candidates tournament in Amsterdam. Petrosian enjoyed a winning positional advantage and Bronstein had let his clock run to the point where it was impossible for him to make four moves without overstepping the time limit.

That was when Petrosian, overplaying his hand by moving rapidly, put his queen en prise for nothing. As ridiculous as that was, it still should not have altered the outcome, except that Petrosian, shocked at his blunder, resigned, completely forgetting about Bronstein’s hopeless time situation. An incredible double blunder!

Event: Amsterdam Candidates

Site: Amsterdam, Netherlands

Date: March 28, 1956

Result: 0-1

White: Petrosian

Black: David Bronstein

1. c4 Nf6 2. Nc3 g6 3. g3 Bg7 4. Bg2 O-O 5. Nf3 c5 6. O-O Nc6 7. d4 d6 8. dxc5 dxc5 9. Be3 Nd7 10. Qc1 Nd4 11. Rd1 e5 12. Bh6 Qa5 13. Bxg7 Kxg7 14. Kh1 Rb8 15. Nd2 a6 16. e3 Ne6

17. a4 h5 18. h4 f5 19. Nd5 Kh7 20. b3 Rf7 21. Nf3 Qd8 22. Qc3 Qh8 23. e4 fxe4 24. Nd2 Qg7 25. Nxe4 Kh8 26. Rd2 Rf8 27. a5 Nd4 28. b4 cxb4 29. Qxb4 Nf5 30. Rad1 Nd4 31. Re1 Nc6 32. Qa3 Nd4 33. Rb2 Nc6 34. Reb1 Nd4 35. Qd6 Nf5 36. Ng5 Nxd6 0-1.