In this week’s column I intended to conclude the evaluation of costs as a performance indicator. This evaluation is intended to provide a prelude to the evaluation of profitability, which follows next. Hopefully, readers would have already recognised that the relation between the cost of producing sugar (per tonne) and the revenue received from its sale (which is largely determined by the ruling sugar price) is one of, if not the most critical determinant of the industry’s profitability. The annual unit cost of producing raw sugar, both for the industry as a whole and for the individual estates, which was presented last week, is on the whole, well in excess of not only current prices but even peak prices over the previous five decades and more. For purposes of this presentation peak prices have been empirically deemed to be those in excess of US20 cents per lb.

As the examination of performance indicators goes forward in this series, it will become clearer to readers that, weaknesses of several factors (including land, labour, and capital) contribute to the very high unit cost of producing sugar. GuySuCo’s Strategic Plan however, has identified “falling production levels” as the main contributor to the industry’s high and rising unit cost and consequently, the source of its consistent generation of financial losses.

Economies of scale

This diagnosis of falling production levels as the principal factor behind high and rising unit costs of sugar production is linked to the notion of economies of scale in the economic literature. The impact of falling production levels suggests that the industry is operating on the portion of its cost/supply curve where unit and total costs rise, when output falters. As was explained more than a year ago (October 14, 2012), economies of scale occur in sugar production, when, as more sugar is produced (that is, the scale of sugar output is expanded) on average, less input costs are incurred for each additional unit of output.

This diagnosis of falling production levels as the principal factor behind high and rising unit costs of sugar production is linked to the notion of economies of scale in the economic literature. The impact of falling production levels suggests that the industry is operating on the portion of its cost/supply curve where unit and total costs rise, when output falters. As was explained more than a year ago (October 14, 2012), economies of scale occur in sugar production, when, as more sugar is produced (that is, the scale of sugar output is expanded) on average, less input costs are incurred for each additional unit of output.

In practice, this becomes likely because (as economists explain it) a greater division of labour is now possible. Thus for example, labour skills can be enhanced (both through training and ‘learning by doing’); more efficient techniques, machinery, and equipment can be introduced; systematic research and development (R&D) can be undertaken; and, specialisation can be more broadly applied to all processes, ( including production, distribution and marketing). These facilitate greater industry efficiency and therefore lower unit costs.

An important caveat is that sugar production is based on an agricultural product, cane. Consequently, the physical constraint of suitable and available agricultural land is especially binding on output. In the case of Guyana, the general consensus among industry analysts is that the outer limit of this land constraint, given the structure and configuration of present day agricultural resource use, is approximately 500,000 tonnes of raw sugar production annually.

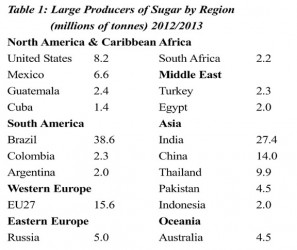

Because the bulk of this sugar would have to be exported, one needs to peruse global competitive sugar producers and exporters in order to compare their potential for reaping economies of scale to Guyana. At present, there are about a score of sugar producers, operating on all continents and major regions of the world, where sugar production (and export) is based on volumes of sugar output that are more than one million tonnes (see Table 1). Obviously, these countries are better placed than Guyana to garner economies of scale. It would be misguided therefore, to expect that economies of scale would give Guyana a superior competitive advantage over other much larger competitive producers and exporters of sugar.

What are returns to scale?

Readers should be aware at this stage that, despite their conflation in popular usage, the two terms: economies of scale and returns to scale are not the same. Returns to scale describe the relation between inputs and outputs as determined by the already established (that is, given) production function or input-output function in the sugar industry. Economies of scale, however, describe a relation where there is an alteration to the established scale of sugar production or output.

In practice, economies of scale can be either internal or external to GuySuCo. When they are internal, they redound to the benefit of GuySuCo (because it ramps up the scale of its operations and output).

When economies of scale are external, these refer to a situation when the sugar industry as a whole (that is, GuySuCo plus independent private cane farmers, and other suppliers) benefit from (as well as may contribute to) the benefits of the reduction in costs, due to the expanding scope of the industry’s operations.

Conclusion: diseconomies of scale

Of note, it is possible that, as the scale of sugar production expands, diseconomies of scale emerge. This can occur if, for example, expanded output increases the complexity of the industry making it more difficult to manage; a good example of this potential for diseconomies of scale can be found in the area of industrial relations at GuySuCo.

GuySuCo’s centralised management structure means that, as its scale of operations increase, every worker conflict or dispute, no matter how local is its origin, has the potential for spreading throughout the entire industry. Furthermore, the industry’s centralised trade union structure reinforces these risks of spreading local disputes industry-wide.

Next week I turn to the examination of profitability.