A number of very important works of literature in the Caribbean that might have been out of print became available in Klaus Reprint, and were republished in Germany in 1970. These included the Trinidadian journals Trinidad (1929-31) and the Beacon (1931-39) and such Guyanese works as Norman Cameron’s The Evolution of the Negro and the anthology Guianese Poetry 1831-1931 edited by Cameron. These are publications of considerable significance in the literature of the Caribbean and of Guyana, given new life by the Klaus Reprint. They might not have been lost otherwise, but were certainly made more readily available and afforded greater prominence.

Similar immeasurable service has been given to Guyanese literature and history by the Caribbean Press in the works it has produced so far. The publications of this press have included The Guyana Classics Series – a selection of works already published but which might have gone out of print.

These were selected because of their importance to the national literature, the prominent contributions they have made in the fields they represent, the nature of the work and whatever qualities may afford them the elevated status of a ‘Guyana Classic.’

![]() The Caribbean Press has thus given the same kind of service rendered by the Klaus Reprints. Some of these publications mark historic milestones in literature and history and represent a library or a collection of some of Guyana’s most important books, all immediately available in one place. They are now circulated for public education, particularly because of their new presence in secondary schools; they add to international access and availability, making Guyana, its literature and history better known; they make the work of researchers somewhat easier and generally enlarge Guyanese letters and stature.

The Caribbean Press has thus given the same kind of service rendered by the Klaus Reprints. Some of these publications mark historic milestones in literature and history and represent a library or a collection of some of Guyana’s most important books, all immediately available in one place. They are now circulated for public education, particularly because of their new presence in secondary schools; they add to international access and availability, making Guyana, its literature and history better known; they make the work of researchers somewhat easier and generally enlarge Guyanese letters and stature.

Included in these reprints are some true classics. Among them is The Discoverie of Guiana (to use its short title), 1595, by Sir Walter Ralegh, regarded as the first work in the history of Guyanese literature responsible for unleashing the story of El Dorado in this region and the unending search for gold. Also reprinted is the first novel focusing on the indentured Indians in British Guiana Lutchmee and Dilloo – a study of West Indian Life, “a critique of indenture practices, bearing witness to the lives of a silenced and exploited population” by John Edward Jenkins. Both authors were Englishmen in the service of king/queen and country producing important landmark documents in the history of British Guiana. To add to those may be The Portuguese of Guyana by Mary Noel Menezes, 100 Folk Songs of Guyana compiled by Lynette Dolphin and Egbert Martin (Leo)’s Scriptology.

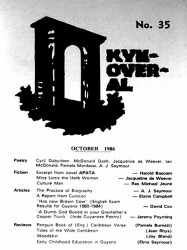

Added to the list of republications is a truly distinguished Caribbean journal, Kyk-Over-Al. The Caribbean Press has reprinted volumes of this literary magazine starting from its first in 1945 with a first printing covering Volumes 1 to 13, 1945 to 1951.

The entire life of this periodical went from its founding by AJ Seymour and both the British Guiana Writers Association and the British Guiana Union of Cultural Clubs of which  Seymour was the secretary, up to 1962. It ceased in that year when the founding editor left British Guiana, but was revived by Ian McDonald who edited it jointly with Seymour from 1984 to 1989, then by himself after Seymour’s death following which he was joined by Vanda Radzik after 2000.

Seymour was the secretary, up to 1962. It ceased in that year when the founding editor left British Guiana, but was revived by Ian McDonald who edited it jointly with Seymour from 1984 to 1989, then by himself after Seymour’s death following which he was joined by Vanda Radzik after 2000.

Kyk-Over-Al was one of the most important journals of its kind in the Caribbean and has been among the longest surviving out of a list of them over a period of more than 50 years. The 1930s and 1940s represented an era when there were several crucial political, cultural and literary developments in the Caribbean. There was a rise in nationalism among the British colonies leading to industrial unrest, struggles for self-government and Garveyism. This also manifested itself in strong cultural movements among both African and Indian descendants, the rise of social realism in fiction and drama and a steady attainment of identity in West Indian poetry.

Newspaper editor and novelist HG deLisser advanced social realism in Jamaica, which was continued in Trinidad by CLR James, Ralph Duboissierre and others, and by Edgar Mittelholzer in BG in 1941. Corresponding trends could be discerned in the drama especially among the Jamaicans, while poetry was still experiencing a movement out of imitation into true national identity. Concurrent with these developments was the rise of the literary journals which served as companions to this literature as well as providing outlets for the advancing work and stimuli for its further development.

In Trinidad in particular, Trinidad and The Beacon which succeeded it, were deliberately devoted to promoting local literature, certainly drove realism and contributed to the region’s literary development. These publications did not survive beyond 1939. Bim was founded in 1942 in Barbados by Frank Collymore and continued for some five decades as one of the main journals publishing West Indian writers. Focus in Jamaica was another, founded and edited by Edna Manley (very famous in sculpture) and operated into the 1950s with much support from novelist Roger Mais and poet MG Smith (better known for his academic career in sociology and social anthropology).

Several others emerged and faded during the second half of the twentieth century. Caribbean Quarterly was the most stable, started by the Extra Mural Department of the UCWI. Tapia came out at the end of the 1960s, changed its name to The Trinidad and Tobago Review and continued into the 2000s. The Jamaica Journal was another that showed stability, but during the same period many others such as Savacou lasted less than 30 years. The newest of these still persists – The Arts Journal edited in Guyana by Ameena Gafoor is just 14 years old.

The Caribbean Press reproduced 30 Issues of Kyk-Over-Al from Volume 1 Issue 1, December 1945, up to Volume 3 Issue 13, Year End 1951. The Press, with General Editors David Dabydeen and Lyn Macedo and Consulting Editor Ian McDonald, republished these with an Introduction by Michael Niblett of the University of Warwick. Niblett surveys the history of Kyk-Over-Al and places it in its context in the development of Caribbean literature. He is right on target with his identification of the various characteristics and phases of the Guyanese literature that are represented in the pages of the journal. It is a thorough study and an Introduction which is a scholarly work in its own right.

The First Issue exhibits a sample of the poetry of the time with one very significant and outstanding piece, ‘Tell Me Trees What Are You Whispering?’ It stands out because of its quality which rises above the often still imitative styles and subjects of the others. But it also stands out as the early work of Wilson Harris who was to emerge 15 years later as Guyana’s most original and innovative craftsman in the field of fiction. Similarly, Harris’s short story ‘Tomorrow’ gives an indication of the kind of work he was to develop through his prolific sequence of novels from Palace of the Peacock in 1960 to The Ghost of Memory in 2006.

A somewhat better picture of the more progressive emerging poetry is to be found in Issue 2, June 1946. This is so because of Harris’s ‘Savannah Lands’ which further reveals his preoccupation with the Guyanese landscape that was to develop famously in his later fiction. But it is also significant because of a reprint of a Leo poem ‘Resuscitation’ which demonstrates the confidence and quality that made Egbert Martin the true founder of modern Guyanese poetry in the 1880s. The poem identifies itself unfettered by the imitative verse of others around it. Added to those are verses which were to become famous in Guyanese literature such as ‘Name Poem’ which shows a developing Seymour and ‘Ode to Kaieteur’ by Walter MacA Lawrence.

Among the most significant pieces in Issue 1 is the survey of ‘Drama in British Guiana’ by Norman Eustace Cameron. This is an extremely useful document which has given priceless assistance to researchers in the area of Guianese drama which appeared somewhat sparse during those years. Further, it is the work of Cameron who was one of the most prominent pioneers in modern Guyanese drama as a playwright himself. In fact, modern Guyanese drama actually began with him in his own efforts (of debatable success) to create a Guyanese theatre.

Of some significance too, is Seymour’s account of ‘Guianese Poetry’ in Issue 2. In the pages of Kyk-Over-Al Seymour has produced several critical accounts which have attempted to define what was taking place in Guyanese and Caribbean poetry. These were held up to serious question by critic Edward Baugh (see his West Indian Poetry 1900-1970), but they are very important in the study of Guyanese literature.

The first issue of Kyk has great historical value in what it shows of the state of the literature, culture and society in 1945 and the strong hints it provides of what was to develop later.