Grief and anguish

The budget debate might be over but not the grief and anguish of the Guyanese people. At least, so it would seem from the ever-widening gap between their income and expenditure, a gap that has been increasing by an average of 11 per cent annually since 2007. Their grief and anguish will continue also as they ponder the slower growth in income and the many necessities and comforts that might remain out of reach. Last week it was observed that the rate at which gross national disposable income increased in 2013 was far slower than in any period over the past five years. This was true also at the household level where disposable income rose at half the rate of one year ago. Indeed, the decline was dramatic and opens the question as to how Guyanese will make ends meet in the circumstances of a tightening revenue situation. More importantly, it also raises the question as to how households in this nation are able to afford the level of expenditure that substantially exceeds their reported income and outstanding consumer debt.

A decline in the rate at which income increased means that it was hardly likely that Guyanese could buy much more than they did in the previous year. Yet, contrary to expectations, private consumption spending rose substantially in 2013. The event is no anomaly since Guyanese consumers have been consuming far more than they have been earning for several years now. Sustaining such spending for long periods indicates that the story of Guyanese consumers and their expenditure behaviour is therefore more complicated than the mere appearance of spending beyond their means.

Insufficient earned income

As this column seeks to reveal, spending has been increasing on an annual basis in the face of insufficient earned income. For spending to increase, households had to obtain additional money from elsewhere. The immediate reaction to that finding is to see if the difference between income and expenses is made up by borrowing. The first thought is always to borrow from family, friends and perhaps fools. But in a scenario where all income is spent, that group might be of little help. As such, the logical alternative is to borrow from the financial institutions or from merchants under their various credit schemes, if one qualifies. The evidence of closing the financial gap through borrowing should show up not only in an expansion of outstanding balances to banks, but more importantly in an increase in the ratio of outstanding loans to disposable income or in the ratio of loans to gross domestic product (GDP).

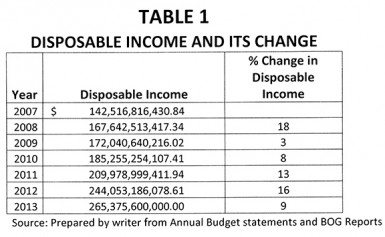

The starting point for this discussion then is the disposable income of consumers and its change as revealed in Table 1 below. The income tax data provided by the government in the annual budget statements supply enough information to arrive at a reasonable estimate of the disposable income of Guyanese workers. The tax computation formula was used to ascertain the income from which income taxes of individuals were derived. Armed with the income and tax collection data, it was possible to determine the disposable income of households.

The starting point for this discussion then is the disposable income of consumers and its change as revealed in Table 1 below. The income tax data provided by the government in the annual budget statements supply enough information to arrive at a reasonable estimate of the disposable income of Guyanese workers. The tax computation formula was used to ascertain the income from which income taxes of individuals were derived. Armed with the income and tax collection data, it was possible to determine the disposable income of households.

The table in reference shows that disposable income has been increasing in nominal terms every year in the period of review. The increase varies from a low of three per cent in 2009 to a high of 18 per cent in 2008, but the movement has been positive in each of the seven years observed. The data is also consistent with the disclosure in the 2014 budget statement that the rate of increase in gross national disposable income declined drastically. In the particular case of workers’ income, there was nearly a halving in 2013 of the rate of increase when compared with that of 2012.

National attitude

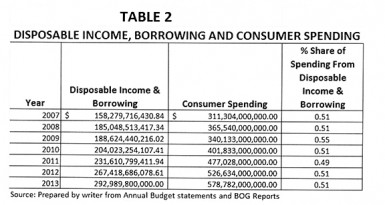

The next table links disposable income and borrowing with consumer spending. An interesting observation is that Guyanese spend all of their earned income on the things that they buy, leaving nothing for a rainy day. It reveals too that, even after attempting to close the financial gap, the money in the hands of Guyanese from clearly identifiable sources is still insufficient to meet their level of demand in the Guyana economy. This type of money management on such a broad scale might suggest a national attitude of living above one’s means or the more troubling prospect that nearly half of the purchases might be financed with undeclared income since there exists a 49-per cent gap between income and expenses. Before hastening to believe the worst, it is necessary to be aware that there could be other explanations for the resource gap.

Substantial transfers

One possibility is that substantial transfers of income might be taking place through remittances and public assistance programmes. Not all transfer payments go to consumers, but even if they did, they would fail to close the gap between income and expenditure. For example in 2013 when remittances are added to the income, Guyanese still need an additional 38 per cent of income to cover their expenses. Another possible explanation for the large gap between income and expenditure could be exceptionally large amounts of tax concessions. The government reduced the marginal tax rate from 331/3 per cent to 30 per cent in 2013. But the government itself in the budget statement indicated that that would only put an additional $1.8 billion in the hands of the spending public. The concession given to low-income workers amounts to $34 billion when calculated using the information provided in the 2013 budget statement. This writer has no data on the size of tax exemptions given to qualified foreign workers who would spend money in the economy. But, the tax concessions could hardly be as large as remittances. Even after adding back the tax concessions, the funding gap still exceeds 31 per cent or $180 billion.

Grave problem

Each of the foregoing possibilities chips away at the financing gap, but none is enough on its own to explain the difference. Their combined impact too is inadequate to assuage concerns about the source of much of the income spent by households. That leaves the real likelihood that persons might not be reporting all the income that they are obtaining. The reasons for the underreporting of income could vary and ought to give rise to serious worry about the depth of the money laundering problem and some of its predicate crimes in this country. It is a large sum of money that is unaccounted for and for which explanations are not sought by the authorities. But whatever the cause, the large unexplained financial gap reveals that there is a loss of integrity in the system for reporting income in this country. This is a grave problem which ought to receive urgent attention by all constituents of Guyana.