Boyd Tonkin recalls a recent pilgrimage to the former home of Gabriel Garcia Marquez in Cartagena and marvels at a writer whose fantasies helped define a country and continent

Last September, I might easily have died in Cartagena de Indias. Our domestic flight had riskily taken off from the Colombian capital Bogota – to Gabriel Garcia Marquez, a “remote, lugubrious city where an insomniac rain had been falling since the beginning of the 16th century” – even though the airport at Santa Marta, its destination on the Caribbean coast, had shut because of a tropical storm.

The deluge over Santa Marta, hardly surprising for the season, continued. In mid-flight the jolting plane diverted to the port of Cartagena. There, on the tarmac, a passengers’ revolt forestalled the pilot’s crazy plan to return straight away to Bogota. By this time, the airport had closed for the night, and the biblical downpour had moved down the coast to soak and shake us. We rescued our baggage almost by force from the hold and ran from the plane, to find that a sharp-witted lady in the terminal had kept open the hotel reservation desk.

So it was that, within an hour of fearing that I would perish as a downpage news item somewhere along the tempest-racked Caribbean shore, I retired to bed amid the colonial-era grace and grandeur of the Santa Clara convent, now a luxury hotel. I woke to a sumptuous breakfast in the flower-filled courtyard in the company of the charming Mateo, the house toucan. No one in a uniform had been looking out for us. The powers that be scarcely cared if we lived or died. Authority was either absent or inept. At the same time, thanks to the kindness and sympathy of strangers, marvels and metamorphoses lay within our grasp. “Gabo”, who has departed at the age of 87, knew all about that.

The lovely 16th-century convent, once also a hospital, has a crypt. In 1994, by then living again in the city of his youth and his dreams, Garcia Marquez published Of Love and Other Demons. That novel, as much an impassioned evocation of Cartagena as the better-known Love in the Time of Cholera, tells of a young journalist sent in 1949 to the newly excavated site of Santa Clara. He has to investigate the miraculous skeleton of a child marquise, dead 200 years but now exhumed with a 22m “stream of living hair the intense colour of copper”. A mood of febrile gothic menace pervades the tale, although the walled city it conjures up could hardly be more topographically exact. The reporter’s editor, Clemente Manuel Zabala, definitely existed. Indeed, he gave the young Gabo his first big break on El Universal.

In Cartagena, on May 21, 1948, the on-off law student and literary wannabe – born inland at Aracataca but raised in Barranquilla on the coast – published his first article. Obliquely, it touched on the curfew and state of siege that had recently gripped the city after the initial massacres of “La Violencia”. At first a war between liberals and conservatives, later the trigger for a general crisis of the state, that internecine slaughter would usher in almost six decades of bloodshed, strife and instability in Colombia.

During those dark days, now largely but not entirely superseded, it sometimes felt as if only the life-affirming prose of one man shone out against the climate of lawlessness, tyranny and barbarism. Gabo became through the leaden years of death squads and drug lords a kind of ideal Colombia, or rather the real Colombia now in exile in his imagination. He not only mesmerised the global republic of letters after One Hundred Years of Solitude appeared in 1967; he also somehow embodied and expressed the soul of a wounded nation, and so helped to heal it as no general, magnate or politician ever could. Now that’s magic realism.

After my unscheduled night at Santa Clara, I knew from a previous visit where I should go. A short walk down the street, past the pastel-shaded houses adorned with hanging baskets of flowers, takes you to the Spanish seafront ramparts that resisted Admiral Vernon’s English fleet in 1741. There, on the corner of Carrera 2 and Carrera 7, sits the squat vermilion block where the writer lived. It’s almost a Garcia Marquez joke. A novelist of superlative aesthetic gifts chooses, after returning from Mexico City in the wake of his 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature, to build and then inhabit the only ugly house in the historic centre of Cartagena. Security still mattered to him, of course: the aptly nicknamed “Typewriter” house sits behind its own high wall.

More than that, this clumsy but functional intruder reminds you that nostalgia and renovation by themselves cannot meet modern needs. As a young man, Gabo had discovered in Cartagena a gorgeous wreck, “no longer sustained by its martial glories but by the dignity of its ruins”. Love in the Time of Cholera portrays the crumbling citadel, in which Florentino Ariza’s love for his sweetheart Fermina Daza ferments over 53 years, seven months and 11 days of hope deferred, as a place of “honourable decadence”, “where flowers rusted and salt corroded, where nothing had happened for four centuries except a slow ageing among withered laurels and putrefying swamps”.

No one did more than Gabo to invoke and even sanctify the gracious, eccentric and story-studded Colombia of the past. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, the forlorn Aracataca of his boyhood mutates via the alchemy of fiction into “Macondo”. The town’s florid miscellany of embroidered yarns, legends and family anecdotes blooms into a universal myth. And the novel’s creation, over a year of feverish inspiration in a small flat in Mexico City from 1965-1966 with every household item down to the fridge pawned by Gabo’s wife Mercedes and the madcap former advertising copywriter wreathed in cigarette smoke as he hammered his Olivetti to the background of Debussy’s Preludes and the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night (the only records he still owned), has turned into a legend to match any in the book.

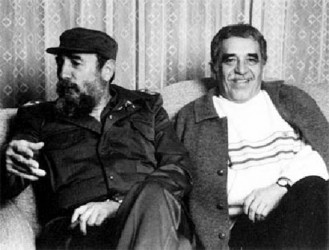

Yet lyrical nostalgia was the port of entry, not the terminus. As with his orange eyesore planted amid the colonial prettiness of old Cartagena, Garcia Marquez always imported a modern sensibility into his recovered world of magic and mystery (even if the real origins of so many characters and episodes led the author to dub himself as just “a mediocre notary”). History, brutal, crude but inescapable, happens in cycles to Macondo, where in any case antique charm had always papered over suffering. He must love Macondo, record it, salute it, but also lay its past and its plentiful ghosts to rest – just as he kills off Colonel Aureliano Buendia, based in part on his adored grandfather, after which act of ancestor-slaying the author wept for two hours. Cuba’s President Fidel Castro (left) pictured with Gabriel Garcia Marquez in 2000. The two friends first met in 1959

From the off, he scrutinises decay and delusion. He deplores the old world’s violence and injustice – towards the poor, the dark-skinned, the unorthodox, the rebellious and, of course, towards women. The poet of tropical languor and sensuality would also become a stalwart friend of Fidel Castro and a champion of revolutions across his continent. That commitment would make him enemies as well as allies. It stoked, for example, the decades-long feud with his fellow titan of fiction Mario Vargas Llosa: almost his equal as a novelist, but the centre-right liberal chalk to his Bolivarian-socialist cheese. However, the haymaker with which Vargas Llosa felled Garcia Marquez at a film premiere in Mexico City in 1976 – what Gabo’s biographer Gerald Martin calls “the most famous punch in the history of Latin America” – had a strictly personal, possibly marital, origin.

By 1950, Gabo had moved up the coast from Cartagena to Barranquilla, by contrast an open, outward-looking town with almost no history and migrants from all over. There he lived in a brothel for a year and began a column for El Heraldo under the pseudonym of “Septimus” – after Virginia Woolf’s “heartbreaking” Great War veteran, Septimus Warren Smith, in Mrs Dalloway. For Woolf had cast a spell on the apprentice author almost as deep as those of Joyce and Faulkner, his twin idols at the time. Five years would pass before his first books surfaced – as a maverick, fearless journalist, which he always remained, in The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor, and as a forger of fiction that transforms memory into myth, in Leaf Storm. In Barranquilla, surrounded by an informal university of like‑minded compadres, his talent began to take on its mature shape.

One of the Lebanese-origin citizens of Barranquilla much later won a global renown of her own: Shakira. Yesterday, the pop diva posted a farewell message to the writer she revered: “Dear Gabo, you once said that life isn’t what one lives, but the life one remembers and how one remembers to retell it.” You might argue that the fundamental paradox of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s career was that he remembered a new world into existence. Out of his excavation of a beautiful but bitter history, doors of creative – even political – change opened for readers and writers not only in Latin America but also around the world.

Like that russet torrent of hair spreading from the dry bones of Sierva Maria in the crypt of Santa Clara, the tormented past flowed out into a brighter, broader future. Or, as the awestruck river-steamer captain muses when he witnesses the “intrepid love” of the aged Fermina and Florentino: “It is life, more than death, that has no limits.