By Joycelyn Williams

A competitive economy must have competitive companies producing goods and services that can compete in the global marketplace in terms of features, quality and price. There can be no competitive economy without competitive products.

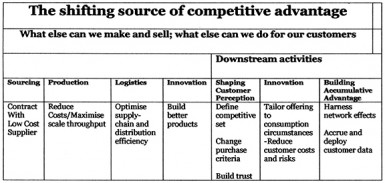

Today’s article is a discussion on this matter. In this era, downstream activities aimed at reducing customers’ costs and risks are emerging as the drivers of value creation and sources of competitive advantage. Years ago, upstream activities such as sourcing, production and logistics were the main drivers of strategy. This change in strategic emphasis for business is something which all firms must recognise.

Downstream activities such as delivering a product or service for specific consumption circumstances are increasingly the reason customers choose one brand over another, and provide the basis for customer loyalty. Companies that do not recognise this, emphasise their products and production and measure success in terms of units moved and how efficiently it was produced. If this new thinking is right, all our companies must observe this emphasis. A recent article in the Harvard Business Review by Niraj Dawar Professor of Marketing in Ontario titled ‘Tilt: Shifting Your Strategy From Products to Customers’ sheds some light on this important strategic issue. Dawar notes that “The strategic question that drives business today is not what else can we make but what else can we do for our customers.” Customers and the market—not the factory or the product—now stand at the core of the business. This new centre demands a rethink of some long standing pillars of strategy.

In this new scheme of things the firm must place greater emphasis on the external linkages with customers, channel partners and with complementary firms on whom it depends for inputs or other supporting services to get and create customers and their loyalty in the marketplace. The major source of value is with the customer in the marketplace. Dawar notes that, “a company is market oriented if it has mastered the art of listening to customers, understanding their needs and developing products and services that meet their needs.” Meeting customers’ needs can yield large premiums for firms that respond. It explains why a customer would purchase a can of coca cola in a supermarket for $125 and then be willing to pay double that amount for the same coca cola on a hot day through a vending machine located at strategic position where the customer is thirsty and craves a coke.

In similar vein, Dawar observes that Facebook’s competitive advantage is not in its sparkling offices or on its premises, nor in its smart employees. Rather, Facebook’s competitive advantage lies in its network and in the opportunity it provides 1 billion people to hang out in its village typesetting. Facebook does everything to keep its position as the “preeminent village square on the internet.” The more users stay on Facebook the more likely their friends will stay.

Zara, the fast fashion retailer places only a small number of products on the shelf for relatively short periods of time. When it sees how the customer responds then it quickly responds with larger volumes of products for which there is great consumer demand. In this way, the company does a great job of keeping its customers satisfied.

Believing that this is the right way to create firm value many large companies spend billions of dollars on focus groups, surveys and social media trying to get “the voice of the customer,” to drive decisions related to products, prices, packaging, store placements, promotions and positioning.

The importance of downstream activities in strategy means that firms must not find much reason to gloat only on production and production efficiency but must be expending more strategic energy to understand the marketplace.

This piece draws heavily from “When Marketing is Strategy” by Niraj Dawar in Harvard Business Review December 2013 Issue.