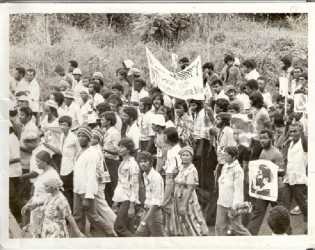

Editor’s Note: Last Friday, June 13th, was the 34th anniversary of the assassination of Walter Rodney. This week, and with his permission, we carry the text of an address given by Barbadian novelist George Lamming at Rodney’s funeral in Guyana, which has recently been published under the title ‘On the Murder of Rodney’ in The George Lamming Reader: The Aesthetics of Decolonisation, edited by Anthony Bogues and published in 2011 by Ian Randle Publishers.

So many Guyanese were born or have come of age after the decades of Walter Rodney’s struggle and ultimate sacrifice – an itinerary that takes us from Guyana to Jamaica, Jamaica to London, London to Tanzania, Tanzania to Jamaica to Tanzania and finally back to Guyana. Too many of us believe that our hopes for this country’s future died with him. But that would be to profoundly miss Rodney’s unshakeable belief in the self-emancipation of working peoples, his rejection of big-man and big-woman, yes-man and yes-woman politics, his insistence that “It is only direct action on the part of the people, your own perception of what is possible, that can produce fundamental change.” He fought against the tyranny of those who claim they have been elected to lead us, against widening economic inequalities, against state repression, against denial to people of the right to vote in national and local government elections.

And he fought against the race divide that festers like an open wound, imprisoning us in our fear and deep suspicion of each other, blinding us to the everyday exchanges that bind us to each other, and resulting in a coastal conflict that cannot but fail to render the struggles of Amerindian women, men and children invisible or secondary.

In the mid 1970s, , at a speech made at D’urban and Louisa Row in Georgetown in defence of Arnold Rampersaud (Rampersaud was a PPP activist who had been arrested and charged with the murder of a police constable in 1974. Amidst much local and international mobilization and attention, he was finally acquitted in 1977), Walter Rodney would remind Guyanese people of the costs of the mutual suspicion, of whose interests it ultimately served:

In the mid 1970s, , at a speech made at D’urban and Louisa Row in Georgetown in defence of Arnold Rampersaud (Rampersaud was a PPP activist who had been arrested and charged with the murder of a police constable in 1974. Amidst much local and international mobilization and attention, he was finally acquitted in 1977), Walter Rodney would remind Guyanese people of the costs of the mutual suspicion, of whose interests it ultimately served:

“…we have had too much of this foolishness of race. I’m not going to attempt to allocate the blame one way or another. I think more than one political party has been responsible for the crisis of race relations in this country. I think our leadership has failed us on that score. I think external intervention was important in bringing the races against each other from the fifties and particularly in the early 1960s. But I am concerned with the present. If we made that mistake once, we cannot afford to be misled on that score today. No ordinary Afro-Guyanese, no ordinary Indo-Guyanese can today afford to be misled by the myth of race. Time and time again it has been our undoing. Does it have anything to do with race that the cost of living far outstrips the increase in wages? Does it have anything to do with race that there are no goods in the shops? Does it have anything to do with race when the original lack of democracy as exemplified in the national election is reproduced at the level of local government elections?…It is clear that we must get beyond that red herring and recognize that it is intended to divide…Those who manipulated in the 1960s, on both sides, were not the sufferers. They were not the losers. The losers were those who participated, who shared blows and got blows. And they are the losers today. It is time that we understand that those in power are still attempting to maintain us in that mentality – maintain us captive in that mentality where we are afraid to act or we act injudiciously because we believe that our racial interests are at stake.”

Walter Rodney’s legacy is a living example, one that is needed today, more than ever. After 34 years, there is finally a Commission of Inquiry into June 13th 1980. It is an opportunity to ask ourselves why younger generations know little if anything of who Walter Rodney was and what he stood for. Why copies of his children’s books, Kofi Baadu Out of Africa and Lakshmi Out of India (there were others planned or in progress) are not available in libraries and schools. Whether the things that Rodney fought for have really been achieved today, and what our responsibilities in the face of this are. Why race continues to be an easy bogeyman to trot out. Why it is important to remind ourselves that the Commission of Inquiry is not just about finding out what happened. We must also ask ourselves what it means to ask these questions from the vantage point of our present, and we must strongly resist those who would attempt to attach themselves to his legacy in order to reap narrow political dividends in the present, dividends that have nothing to do with healing, reconciliation and social and economic transformation, dividends that Rodney ultimately gave his life to oppose.

For Walter Rodney: George Lamming, June 1980

Citizens of Guyana, and the islands of the Caribbean, Comrades and friends from beyond the region, I speak to you as one who has loved this country, as one who ever since his first visit 25 years ago had always applauded the Guyanese as perhaps the kindest and most hospitable people in this Caribbean region. As one, who in the year of your independence amidst some controversy was even given the assurance by the then and present Prime Minister that he had earned the right to speak freely in this land on matters of common concern to the region. There have been great changes in fortune and method in your country, including the ungracious curtailment of my stay among you to a brief 48 hours, and yet I experience no change in the quality of my affections for this place.

Sometimes it may take a death and a special kind of dying to quicken the truth that is not urgently alive in our own consciousness. Today, we meet in a dangerous land, and at the most dangerous of times. The danger may be that supreme authority, the supervising conscience of the nation, has ceased to be answerable to any moral law, has ceased to recognize or respect any minimum requirement of ordinary human decency. Walter Rodney’s death like the manner of his dying, has quickened this truth and provoked within and beyond Guyana a rage and grief which official authority could never have anticipated. To turn murder into a mockery of the dead is the ultimate blasphemy against all forms of living. But this is not new, although history may record that at this time Guyana has made its own contributions to a long, long tradition of nightmare and terror which has always been at the heart of the history of these Americas.

For democracy has never, never, been an organic part of our experience, from conquest through slavery and colonization to the present arrangements we endure. The need for democracy is often a conscious and courageous effort to exorcise those twin demons of the tyrant which have pursued us from the past.

What did Rodney represent that was so special? And what is it about his loss to us that has caused such sorrow? His closest colleagues will have their answers. I speak as a man of the Caribbean who knew him through conversations over the years, through correspondence and through his work as a historian, a teacher and an intellectual worker among those who had been deprived of his advantages.

He was, first of all, a serious man; and that, in our territories, does not always make for comfort. He was not ‘smart.’ He was not ‘bright.’ He did not seek to score points for the sake of argument. But he had a rare gift of intellect to which he felt a special duty. It was a tool, a reservoir of power which could only justify itself if it were put into service, and on behalf of social need. He was an intellectual in the sense that all men and women are intellectuals. For to be alive is to have a concept, a view of life, to be engaged in or be condemned to making choices about your actions.

But Rodney impressed us by a constant struggle to live his view, to bring to his work, as a historian and teacher and political comrade, a certain integrity of commitment. It is as though he wanted to live each day as though it were his last.

This gift of seriousness, this struggle for personal decency, and this courage, left their impression on all who came within his influence from Africa to the Americas, to Europe and back to the heartland of Guyana which he loved.

I came in this morning from Barbados which is known to be a country of excessive stability, and I am really struck by the deep respect and affection which he has generated among the most conservative elements in that country. And I was hearing a story this morning on the plane as we cane in of a simple woman hearing Rodney on the radio, and her only comment was “He must be a Christian.’

To his wife, Pat, and their children, to his mother and immediate family, I take this liberty of saying that all his comrades embrace you. We thank you for the contribution you made in the shaping and creation of so fine a human being. And we walk with you now and into the future.

A few weeks ago I received a letter from Walter telling me of the completion of the first part of his History of the Guyanese Working People. It ends with this sentence:

There is still much work to be done here, but I expect that we will meet at the rendezvous of victory.

I think we shall meet; since the struggle for humanity in this region will always be identified with his name; and any just victory will have been influenced by the powerful contribution of his intellect and the gentleness of his caring. And so I close with the poem which Martin Carter gave me this morning:

For Walter Rodney (Martin Carter)

Assassins of conversation

They bury the voice

They assassinate, in the beloved

Grave of the voice, never to be silent.

I sit in the sky’s wild noise

Of the feet of some who

Not only, but also, kill

The origin of rain, the ankle

Of the whore, as fastidious

as the great fight, the wife

of water. Risker, risk.

I intend to turn a sky

of tears, for you.