Newly re-elected Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos’ proposal to prohibit successive presidential re-elections is the best political initiative I have seen in South America in recent years. It should be turned into a regional example to redress the wave of authoritarianism that has swept the region in recent years.

A day after his Sunday reelection in a tight race — his main opponent, Oscar Ivan Zuluaga, had accused him of moving the country toward the kind of authoritarian leftist populism championed by late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez — Santos announced that he will send a bill to the Colombian Congress to ban presidential re-elections, and to extend the current four-year term to five- or six-year terms starting with the next president.

“We are going to introduce a series of reforms, including the elimination of re-election and the extension of presidential terms,” Santos said in his first press conference after the election.

Many Colombian political analysts with whom I talked this week, including some Santos critics, agree that banning re-election is an excellent idea. Since former President Alvaro Uribe passed a law in 2004 to allow presidential re-elections that allowed his own re-election in 2006, both Uribe and Santos have used massive state resources to advance their respective political careers, they say.

Many Colombian political analysts with whom I talked this week, including some Santos critics, agree that banning re-election is an excellent idea. Since former President Alvaro Uribe passed a law in 2004 to allow presidential re-elections that allowed his own re-election in 2006, both Uribe and Santos have used massive state resources to advance their respective political careers, they say.

Indeed, Colombian presidents have become increasingly stronger — appointing their own Central Bank nominees, judges, comptrollers and other key officials for up to eight years — and institutions have become weaker, endangering the country’s system of checks and balances.

Now, if the Colombian Congress prohibits successive re-elections, as expected, Colombia would mark a welcome departure from the recent wave of Chávez-inspired “saviours of the fatherland” in Ecuador, Bolivia and Nicaragua, who after being democratically elected changed the rules of the game to grab absolute powers and become elected dictators.

In Ecuador, President Rafael Correa, who as recently as in his second-term inauguration speech on May 24 last year promised to step down in 2017 after finishing his current four-year term, announced earlier this month that he wants to change the constitution to allow the indefinite re-election of all public servants, presumably including himself.

Correa, whose country’s economy boomed thanks to rising oil prices last decade, has censored independent media, persecuted political opponents and has been accused by his own brother of massive corruption.

As for his previous vows not to seek a new term in office, he said recently that “my life no longer belongs to me: it belongs to my people and my fatherland.” It sounds like a line from a fictional tropical dictator, but it’s not.

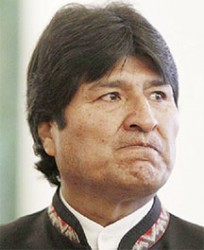

Bolivia’s President Evo Morales, who following Venezuela’s Chávez script has clamped down on opposition media and political opponents ever since winning elections in 2006, recently predicted that he will win the upcoming October elections with 74 per cent of the vote.

Morales may indeed win by a huge margin: he controls all major institutions, including the electoral tribunal, and has promoted a personality cult that now includes an allegedly educational government-

published children’s book entitled Evito’s adventures, glorifying the president’s childhood. Unless Bolivia’s opposition leaders unite in a single bloc, Bolivia’s next Congress is almost sure to change the constitution to allow for Morales’ indefinite re-election.

In Nicaragua, opposition leaders who refuse to join forces and a business community that seems to care very little about the country’s future have helped President Daniel Ortega become a virtual president for life. In January, the Ortega-controlled National Assembly passed a constitutional reform that allows for Ortega’s indefinite re-election.

Of course, ‘maximum leaders’ have existed in Latin America for the past two centuries. But they have re-emerged with renewed energy since Chávez and other narcissist-Leninist leaders started benefiting from a boom in world commodity prices in the first decade of the 21st century. Argentina’s President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner would have certainly tried to change the constitution to run for a third term if her party hadn’t lost a Congressional super-majority in a recent mid-term election.

My opinion: Santos’ announcement that he will present a bill to prohibit successive re-elections in Colombia is great news. Now, Colombia’s president should turn it into an example for the rest of the region.

It would expose many of his neighbouring countries for what they really are — cosmetic democracies — and could mark the beginning of a new trend toward the re-establishment of the separation of powers in South America. That would be the best antidote against the massive government corruption, political repression and disastrous economic experiments that we have seen in the region in recent years.

© The Miami Herald, 2014. Distributed by Tribune Media Services.