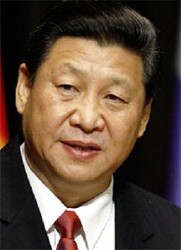

BEIJING, (Reuters) – President Xi Jinping’s crackdown on corruption has sown so much fear that many Chinese officials are doing anything to stay out of trouble – from dithering over approving big-ticket projects to seeking early retirement.

A small number of top executives under investigation at state-owned enterprises have even committed suicide.

While the campaign has been a hit with a public usually sceptical about such crackdowns, it’s having an unintended consequence, said bureaucratic sources and officials at state enterprises: Those supposed to implement much-needed economic reforms and run the machinery of government are dragging their feet because they are scared of attracting unwanted attention.

One reason for the fear is that Xi’s 18-month-old campaign shows no sign of faltering – it claimed its biggest scalp so far last week when the government said it would court-martial a former top army general for taking bribes, the most senior officer ever felled in a Chinese graft probe.

Another is that with corruption so endemic in China – especially in government procurement, the energy and construction sectors and the awarding of land-use and mining rights – many officials know they could be next.

“The anti-corruption campaign is having a big economic impact. Local officials are no longer keen to launch investment projects – they are laying low,” said a government official in the eastern coastal province of Zhejiang, where Xi served as Communist Party boss from 2002 to 2007.

“People thought it would be short-lived, just like the others.”

Some sources said large projects were attracting increasing public scrutiny on the Internet in China, even if there was no suggestion of graft, prompting officials to be cautious. A number of projects have been shelved in the past year, for example, after ordinary Chinese raised environmental concerns.

“FEAR AND UNCERTAINTY”

To be sure, the anti-corruption campaign is not the only reason some officials are unproductive.

Policy implementation has often been a problem in China. Any policy that could erode local government influence and reduce revenues might also face resistance, a key issue since Xi has pledged to allow market forces to play a decisive role in the economy by scaling back government intervention.

While there is no data to show the crackdown is hurting the economy, Huachuang Securities in Beijing estimates a separate campaign against official extravagance may have knocked 0.4 of a percentage point off China’s growth last year of 7.7 percent.

The party’s anti-graft watchdog said in March that money spent on meetings and official overseas trips fell by about 53 percent and 39 percent respectively from 2012. That campaign has worried firms that supply premium liquor, expensive watches and luxury cars, as well as high-end hotel chains.

None of the dozen bureaucrats and state company officials interviewed by Reuters wanted to be identified because of the sensitivity of the anti-corruption drive.

But they gave similar accounts that illustrated how deeply the campaign is reaching into the halls of Chinese bureaucracy.

One Chinese civil servant in Beijing said officials in her office were recently asked to fill out forms detailing not only the value of their assets but where their children and other close relatives lived to see if any were abroad.

Xi’s campaign has targeted so-called “naked officials”, the term for people whose spouses or children live overseas. Those officials are sometimes suspected of using such connections to illegally move assets.

“There is an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty,” said the civil servant. “Nobody is willing to do anything which may attract unwanted attention. This means little gets done around the office at the moment.”

Xi kicked off his crackdown when he took over the ruling Communist Party in November 2012, partly to try to improve the image of the party and government, which has suffered given the enormous wealth amassed by some officials.

Nevertheless, despite a few pilot schemes for low-level officials to disclose their assets, any public discussion of the wealth of senior leaders remains off limits.

Reuters also reported in April that Xi was purging senior officials suspected of corruption to put his own men and reform-minded bureaucrats into key positions across the party, the government and the military.

About 30 senior officials at the provincial and ministerial level or above have been put under investigation for corruption since December 2012, the official Xinhua news agency said on June 30.

That was having a chilling effect, some of the sources said, adding some officials were seeking to retire early to avoid attention.

“Don’t get into trouble and get arrested, that’s their mentality,” said Niu Bokun, an economist at Huachuang Securities in Beijing.

JUMPING OFF BUILDINGS

As Xi’s anti-graft campaign gathers pace, there has also been a spate of suicides among some senior figures under investigation.

The official China Youth Daily reported in April that of 54 officials who died from “unnatural causes” between January 2013 and April 2014, more than 40 percent killed themselves. Eight jumped to their deaths from buildings, the paper said.

Executives at state-run enterprises in China are usually referred to as officials.

Bai Zhongren, former president of China Railway Group, fell to his death in January, following a corruption probe into the now-defunct railway ministry. The former chairman of Harbin Pharmaceutical Group Sanjing Pharmaceutical Co., Liu Zhanbin, died in a similar manner in May while being investigated for corruption.

In an apparent sign top leaders know bureaucrats are keeping their heads down, Premier Li Keqiang pounded the table during a meeting with provincial officials in May, blasting them for not “doing a stroke of work”, state media reported.

The following month, the People’s Daily – the party’s mouthpiece – issued three front-page commentaries slamming local officials for their slackness and for “avoiding the limelight”.

“Local officials have adopted a ‘wait and see’ approach as the anti-corruption campaign intensifies,” said Nie Wen, an economist at Hwabao Trust in Shanghai. “It’s having a big impact on the economy.”