Introduction

This week’s column continues the discussion of the Bureau of Statistics (BoS) Preliminary Population and Housing Census Report for 2012. Last week’s column had focused on the intercensal population decline between 2002 and 2012. A larger intercensal population decline had been recorded between 1980 and 1991, which was the first occurrence of a decline in Guyana’s census history. In its Final Census Report for 1991 the BoS had attributed that decline to exceptional outward net emigration as no other population events were evident from the fertility, birth and death rates it analysed for this period.

This week’s column continues the discussion of the Bureau of Statistics (BoS) Preliminary Population and Housing Census Report for 2012. Last week’s column had focused on the intercensal population decline between 2002 and 2012. A larger intercensal population decline had been recorded between 1980 and 1991, which was the first occurrence of a decline in Guyana’s census history. In its Final Census Report for 1991 the BoS had attributed that decline to exceptional outward net emigration as no other population events were evident from the fertility, birth and death rates it analysed for this period.

The 2012 Census Report is preliminary and does not include a presentation of these demographic features. The inference is that the population decline recorded in the 2012 Preliminary Census is also due to exceptional net outward emigration. Indeed, the trend in the available data for births and deaths, visa applications, and immigration records during the years of the census period seem to support this inference, whatever might be the reservations concerning their accuracy.

As a rule, one observes worldwide that high levels of emigration result in two major manifestations. One is that proportionately this emigration is weightiest among those strata of the population with technical skills, expertise and training, and who are otherwise experienced. The second manifestation is that those countries with small populations (like Guyana) have high ratios of emigrants living abroad (the diaspora) to their resident population. Indeed most Guyanese today, assume that at least as many of them live in the diaspora as are still residing here. This emigration phenomenon is termed human capital flight or more popularly brain drain.

Brain drain

I do not have space in this column to consider the many complex economic, social, cultural and developmental aspects of the impact of brain drain on the development prospects of poor countries as a group or Guyana alone. What I wish to debunk here, however, is the tendency for Guyanese commentators to seemingly accept the widely held view that the large sum of remittances, which migrants living in the diaspora send back to Guyana, substantially compensates for the country’s brain drain.

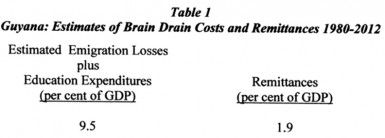

Social scientists have attempted to measure 1) the monetary value of emigration losses and then add to this 2) monies spent on educating and training emigrants. This sum provides a proxy measure of the ‘costs’ to Guyana of outward migration of its skills. This sum is then compared to the value of remittances that the country receives. Such a measure is very rough indeed. There are many omissions including the impact on Guyana’s development caused by the decline in the educational level (and therefore potential productivity) of Guyana’s labour force, after such significant skills loss. Nonetheless, it is worth noting the results obtained for Guyana using these rough measures are highly skewed against brain drain as a net generator of value for the economy. The data in Table 1 indicate the calculations for Guyana for the period 1980-2012.

Source: Inter-American Development Bank, 2014

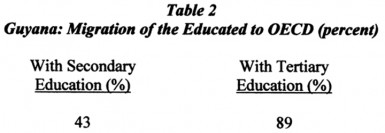

The source from which these estimates were obtained IDB (2014) has also provided estimates of the percent of Guyanese migrants to OECD countries by their educational level. These data are shown in Table 2.

Source: Inter-American Development Bank, 2014

The same source also indicates what Guyanese have repeatedly heard over the past four decades, which is in the 1980s well over 80 percent of the graduates of the University of Guyana were migrating. This was one of the highest levels of human capital flight (brain drain) recorded for a country not at war, engaged in civil war, or faced with serious insurrectionary conflicts. Indeed the data cited in the table also reveal that Guyana was the third highest in Caricom for secondary education emigrants to the OECD and the highest for tertiary education level migrants.

Drivers

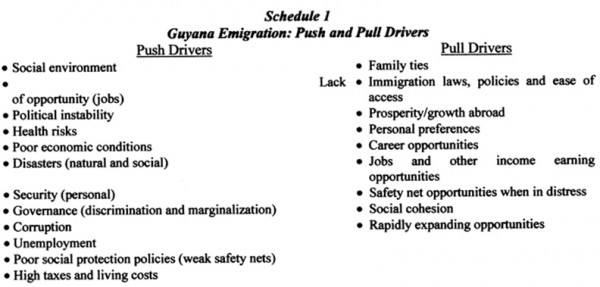

There are many drivers of the brain drain in Guyana. Most of these also explain the more general population migration. Some analysts organize the drivers into push and pull factors, while others group them into categories such as economic, social, security (both personal and national), political, religious, personal and global inequality. The information in the schedule provides a listing of some of several difficult push and pull drivers operating in Guyana.

The information in the schedule suggests that the push factors are in several instances the reciprocal of the pull factors. Thus while poor depressed economic conditions push brain drain and these are reciprocated in the pull of job, income earning, and skills training possibilities in the countries to which educated Guyanese emigrate.

Conclusion

The major conclusion to be drawn from this column is that, if exceptional net outward migration was at the basis of the population decline between 2002 and 2012, then that period, more likely than not, witnessed the continuation of runaway levels of human capital flight or brain drain.

Next week I shall address other key features presented in the 2012 Preliminary Population and Housing Census Report.