Autobiography will come in various forms, often in varying degrees of factual information and different postures of pretence. Some of them just plainly give you the truth, although what you are likely to get quite often are versions of the truth – or a point of view. So that even though autobiography is known to be someone’s life story told by themselves, you really don’t always know what you are going to get.

A brief review of the types is not only interesting, but has some relevant bearing upon the account of a life that we are about to analyse. Some autobiographies take the form of a documentary – the facts are presented in good faith, events are written, described or narrated in plain prose. Nothing else is attempted, although with the best of intentions these will really be the author’s version of the facts. Memoirs are sometimes called memoirs, and reflect the author’s unpretentious personal memories told from his point of view.

Quite a different genre is fiction, based on autobiography, but written as fiction. This is the strategy of countless novelists, most times writing to an unsuspecting audience. In many novels the author uses real information from his life to write fiction, or the truth is fictionalised. Very often too there is fiction which claims to be history – a fictional character claiming to write true things about his life. Imaginative literature posing as the truth is a well-used ploy of novelists presented in various clever ways. A master at that is Wilson Harris, who created the “fictional autobiography” pretending to be written by “WH” – a tactic too complex to be described here.

Quite a different genre is fiction, based on autobiography, but written as fiction. This is the strategy of countless novelists, most times writing to an unsuspecting audience. In many novels the author uses real information from his life to write fiction, or the truth is fictionalised. Very often too there is fiction which claims to be history – a fictional character claiming to write true things about his life. Imaginative literature posing as the truth is a well-used ploy of novelists presented in various clever ways. A master at that is Wilson Harris, who created the “fictional autobiography” pretending to be written by “WH” – a tactic too complex to be described here.

Many autobiographies then, are creatively written, while some imaginative writing pretends to be autobiography.

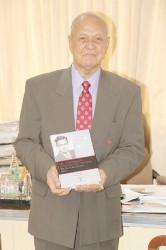

There are mixtures of the two. Reaching for the Stars: The Life of Yesu Persaud Volume 1 by Yesu Persaud is autobiography creatively written – to the point where one could say, to some extent written like a novel. It contains facts – several obvious and undisputed facts, many revelations not previously known, versions and points of view, but creatively written. Judging from our assumptions about the author’s intentions, it wants to tell truths, but the truth is beyond facts – it moves into the realms of belief, principles, teachings and beauty; generally beautifully written.

Dr Yesu Persaud is a prominent personality of renown, power and influence in Guyanese society, one of the leaders of industry, and from the history, a shaper of it. He has held several important positions including Chairman of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL), Founder and Chairman of the Institute of Private Enterprise Development (IPED), Founder and Chairman of Demerara Bank, inter alia. He rose from a worker in the cane fields to a leader of the Guyana sugar industry, represented the government in negotiations for the nationalisation of Bookers and Sandbach Parker. He is an Associate Fellow of the Centre for Caribbean Studies at the University of Warwick, which conferred an honorary doctorate upon him and named the centre after him.

Reaching for the Stars is only the first volume of the long account of his long prolific life. Persaud received much assistance from David Dabydeen (substantially of Warwick University) and hard scrupulous editing from Lynn Macedo, and the work is published by the Caribbean Press. The autobiography is very detailed, with sometimes an over-abundance of information, but it is never dull. It is very tightly written and reads like a novel. After the historical background in chapter one, it is a first person narrative told by the hero. The story begins with the history of Persaud’s ancestors and family, it includes hard historical information, but above all it is a dramatic narration – a story with a hero.

There is always very good delineation of characterisation; real people, but scrupulously painted characters. There is excellent control of audience sympathy in a ‘rags to riches’ tale about the hero, possession of the right qualities and endurance through severe hardships. There is a hero who triumphs; the reader knows he will triumph and knows there will be a happy ending, but the narration manages to be extremely engaging. There is still great suspense leading the reader to always want to know what will happen next and how events will unfold.

There are outright moralistic intentions. One gets the impression the author wants to teach lessons, to instil wholesome qualities in his reader, and often uses himself, his experiences as examples. At points in the story the author runs the risk of coming over as too moralistic, too saintly, too unflinchingly disciplined. He is chaste; consistently loyal to his wife; women approach him – these approaches are sometimes undisguised by any subtlety or suggestiveness, but he rejects them every time. He is so well behaved, readers will be relieved and rejoice when he actually kisses a girl, takes a drink (I mean alcohol), deals harshly with a miscreant or shows some devilish trait.

But clearly, Yesu Persaud belongs to a rare type: he is what is called a “new man.” The concept of the ‘new man’ might be a reaction to the common assumption that a ‘real man’ is rough, promiscuous, amoral, with no time for such betrayals of weakness as domesticity, family chores and human compassion. Persaud believes in chastity, is a family man, is governed by reason and decency. He is of a traditional breed, believes in modesty, decorum, and uncompromising appropriate behaviour. The book seems to have a purpose of attempting moral influence over its audience; by his exemplary behaviour, the hero encourages good qualities, perseverance, struggle and ambition.

This account is characterised by crisp writing and emphatic honesty. It is convincing because readers come to feel they can trust the narrator who is not shy to reveal close personal details and confessions. Several questions will naturally arise, not only about personal things, but because the audience will know Persaud’s personal involvement in corporate work and dealings of high national and international levels. What terrible secrets of industry lurk behind the curtains of big business, behind nationalisation, the sugar industry, the boardrooms of Sandbach Parker, Booker Tate, Sir Jock Campbell, colonialism and liberation?

Yesu Persaud has been deeply involved in these and the book does not disappoint in this regard. He covers these events with not only dramatic detail, but with a point of view. He betrays himself a nationalist and even at times projects an anti-colonial slant. He takes a political interest in the outcomes of negotiations and attitudes towards Guyana’s national industries. Underlying his accounts is a sense of decolonisation – occasionally proletarian sympathies, which are expected of him considering his family background. The book contains a great volume of history, and not only about sugar and the corporate industries. There are vivid pictures of old Georgetown, with an impact and presentation reminiscent of Edgar Mittelholzer. This reference to that master of prose is a compliment paid to Persaud’s narrative. What they reveal about the old life and environment recalls what Mittelholzer did for New Amsterdam and old Georgetown.

When I was asked to review Dr Persaud’s manuscript I was just about to go to a meeting overseas with documents to read and prepare in addition to other commitments. I was wondering how unwise I was to have agreed to read it when I looked at the task ahead. It was a bulky, very daunting manuscript – page after page of non-fiction prose documentary. I confronted the 226 page document late one night – and never put it down. I started late that night and was still reading at dawn. Reaching for the Stars: The Life of Yesu Persaud is that kind of book. It is interesting, engaging and addictive; never dull. After reading each page, you are magnetically drawn to the next one.

At the end of a poem in which the imagination serves to fill in details of people’s lives and situations that are suggested but not documented, John Keats declares “Beauty is truth, truth beauty; that’s all ye know / On earth and all ye need to know.” The workings of the imagination are beautiful in the pictures created and somehow we can accept it as a truth. Truth is a concept that is not to be expressed merely in factual accuracy, it is much more than the facts themselves. When you find truth, you have found a thing of beauty, and then, according to Keats, the real facts don’t matter.

Persaud’s accounts are factual. At least we accept them to be so and hardly look to question that he has documented the truth. Yet it is told from his very personal point of view. But he is aiming at truth, which is to say, more than his version of the facts which are mostly well documented. It is message oriented and the author wants to inculcate in his audience a beauty which lies in being true to principles and integrity, and the rewards that they can bring. This is only Volume One, and one can imagine that many more revelations are in store when the second volume is released.