By Janette Bulkan and John Palmer

Why is it important to know about the Bai Shan

Lin forest empire?

Because the President, Ministers and the Guyana Forestry Commission have given almost unqualified statements of support for this Chinese transnational logger without apparently caring about the non-compliances with laws and regulations and without being bothered by the non-conformities with national policies. As the Secretary of the Rockstone Loggers Association was quoted, ‘if the big ones are not adhering to (the laws), then why should the small ones adhere to (them)?’ (Guyana Chronicle, ‘The Bai Shan Lin affair’, 18 August 2014). The extravagant promises of inward investment, of creating new factories and adding value to forest products have yet to materialise during the eight years since 2006, while intrinsically high-value timbers are being shipped by Bai Shan Lin as raw unprocessed logs to its associated factories in China in ever increasing quantities. Civil society in Guyana is entitled to know how laws, regulations and national policies are being ignored or side-stepped at high levels in government. This analysis is based on GFC figures and documents except where explicitly stated otherwise

What the GFC stated on 18 August 2014

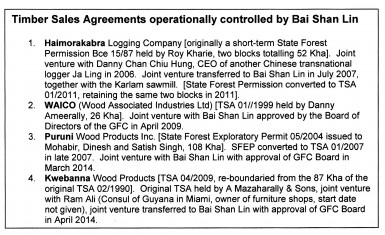

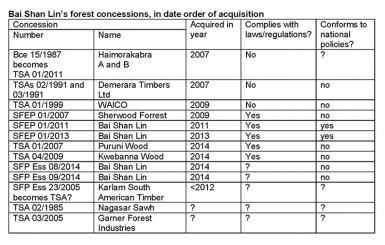

The Guyana Forestry Commission (GFC) and the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment (MNRE) have different histories of which Guyanese-held forest concessions in State Forests have been sold to or have joint ventures with Chinese transnational logger Bai Shan Lin (BSL), and when they were sold or transferred. The GFC itself started with a small number at the beginning of August 2014 and has gradually revealed more and more concessions under the operational control of Bai Shan Lin. The box below summarises how the GFC Commissioner explained the forest holdings of Bai Shan Lin at the GFC Press conference on 18 August 2014, from the earliest to the latest long-term large-scale Timber Sales Agreement (TSAs) [Kha = thousands of hectares by area; information in square brackets includes additional information from GFC sources] –

Two short-term State Forest Permissions, Ess 008/2014 and Ess 009/2014, each of 4,085 ha, directly held by Bai Shan Lin.

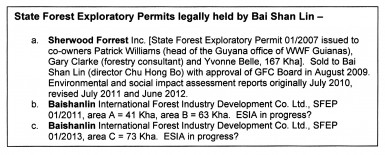

Three 3-year State Forestry Exploratory Permits adjacent or near-adjacent and directly held by Bai Shan Lin in the upper Essequibo –

This gives a total of 274,053 ha in 4 long-term, large-scale joint-venture TSAs, 8,170 ha in 2 short-term, small-scale SFPs held directly by BSL and 344,839 ha in SFEPs held directly by BSL; grand total 627,062 ha as estimated by the GFC on 18 August 2014.

What the GFC omitted to say

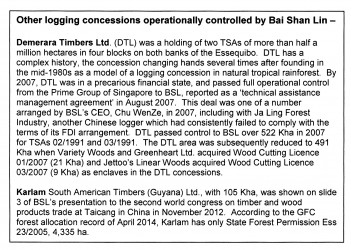

There were two major omissions from the catalogue of concession ownership provided by the GFC Commissioner: DTL (491 Kha) and Karlam (105 Kha).

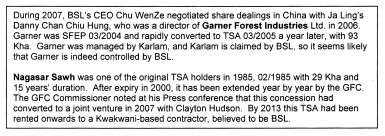

It is widely rumoured ‘on the street’ that BSL also controls Garner (93 Kha) and one of the Nagasar Sawh (29 Kha) concessions –

Adding these four logging concessions (718 Kha) to the previous 627 Kha gives a total under BSL control of 1.346 million hectares, second only to Barama’s 1.611 million hectares.

It is noteworthy that BSL claimed control of 960 Kha in December 2012, and that Minister Robert Persaud asked for a retraction on 15 July 2014, while answering parliamentary questions. BSL has shown no sign of retracting its claim subsequently.

Legality of acquisition of BSL’s forest empire?

During the last three weeks, since early August, the GFC has repeatedly stated that Bai Shan Lin’s forest empire is entirely legal and complies with Guyana’s laws and codes of practice. We now examine this claim, after hearing the personal statement that the GFC’s Corporate Secretary is a ‘stickler for legality’.

The GFC Commissioner and Corporate Secretary were explicit on 18 August that prior to 2009 there was no requirement for a joint venture to have prior government approval. These civil servants appeared to have forgotten entirely that there were repeated calls in the independent newspapers in 2007 for compliance with laws, regulations and formal procedures, during the months that BSL was beginning its empire building; see for example ‘Concession holders who cannot operate their forests should lose their grants, not be allowed to transfer them without a competitive bidding process’, Stabroek News, 11 July 2007, where the illegal but common practice of ‘landlording’ of forest concessions was explained with reference to what the Forest Regulations 1953 and the TSA licence actually state.

Landlording continues to be illegal

‘Landlording’ is the practice in which the legal holder of a forest harvesting concession gives up managerial control and rents it out to another enterprise. The practice is illegal under Forest Regulation 12, 1953.

‘No transfer or any lease or timber sales agreement shall be made by any forest officer without the prior approval of the President where such lease or timber sales agreement grants exclusive rights to any person over an area estimated to exceed three thousand acres or is for an unexpired period exceeding three years’

Note that eight years after the drafting of the Forest Bill 2007 the GFC has still not prepared regulations subsidiary to what is now the Forests Act 2009 (activated in August 2012 and backdated to October 2010). So the Forest Regulations 1953 are still in legal effect.

Moreover, landlording is illegal under Condition 13 of Timber Sales Agreements –

‘The grantee shall not transfer, sublet, mortgage or otherwise dispose of any interest arising under this agreement except in accordance with the Forest Regulations and any purported disposition made except in accordance with such regulations shall be null and void’

Much the same wording is found in the third edition of the GFC Code of Practice for forest operations for Timber Sales Agreement and Wood Cutting License holders (published on the GFC website in mid-2014; clause 11 of the general terms and conditions, annexe 5, page 195) –

‘11. The concessionaire shall not transfer, sublet, mortgage or otherwise dispose of any interest arising under the concession agreement.’

The choice of 2009 by the GFC staff as the first year for approval of joint ventures appeared to be based on a belief that the passage of the Forest Act 2009 by the National Assembly in January of that year meant that it entered into force immediately. In fact, Presidential assent was delayed by a possible world-record-breaking 628 days by then-President Bharrat Jagdeo, and the commencement order required by section 1 of the Act was only signed by Minister Robert Persaud on 08 August 2012.

In law, therefore, the Forests Act 1953/1997 continued to be the operational forest law until August 2012. Activities contrary to that law and its associated Forest Regulations 1953 were illegal until August 2012. All the so-called ‘joint ventures’ – actually, landlording – devised until August 2012, and all the approvals of such landlording by the GFC Board until August 2012, were illegal unless approved for TSAs by the Minister of Forests (the President). There is no evidence in the public domain that former President Bharrat Jagdeo gave prior formal approval to any transfers under Regulation 12 of the Forest Regulations or Condition 13 of the Timber Sales Agreements. The emphasis is on ‘prior’; there is no legal provision for retroactive approval.

There is also no evidence in the public domain that the GFC Commissioner gave prior formal approval to transfer of State Forest Permission Bce 15/1987 to Bai Shan Lin, as required by Condition 2 of 16 of State Forest Permissions.

That means that the following renting or private sales of forest concessions – ‘joint ventures’ – were probably illegal (pending contradiction by formal publication of such prior approvals, with date-stamping of signatures before the dates of any joint venture contracts). The total area of these probably illegal rentings or joint ventures is 762 Kha, over half of BSL’s forest empire in Guyana.

►Haimorakabra SFP Bce 15/87 in 2006 and 2007, 52 Kha;

►Demerara Timbers Ltd TSAs 02/1991 and 03/1991 in 2007, 492 Kha – that no shares may actually have been transferred is not a defence because Condition 13 of the TSA licence refers to ‘any interest’, not just the company shares;

►Waico TSA 01/1999 in 2009, 26 Kha;

►A Mazaharally TSA 02/1990 or TSA 04/2009, 87 Kha, when rented variously to Barama and to Ram Ali, but not when passed to BSL in April 2014 – that latter transfer was legal;

►Karlam South American (Guyana) Timber, details missing, 105 Kha.

Possibly illegal were the rentings of Nagasar Sawh’s TSA 02/1985 (29 Kha) and Garner’s TSA 03/2005 (93 Kha) but information is not confirmed.

However, the following transfer deals were legal, for SFEPs under the 1997 amendment to the Forests Act 1953, and for TSAs under the Forests Act 2009 as activated in 2012.

►Sherwood Forrest SFEP 01/2007 in 2009, 167 Kha;

►Puruni Wood Products TSA 01/2007 in 2014, 108 Kha;

►Kwebanna Wood Products TSA 04/2009 in 2014, 87 Kha.

Although the illegalities of renting logging concessions were exposed repeatedly in the independent Press in early 2007, at the time of the Barama ‘bad-faith contracts’ with Amerindian communities Akawini and St. Monica in Region 1, the GFC continued to allow the other three Asian-owned logging companies to rent concessions: Bai Shan Lin, DTL and Ja Ling.

The chaotic situation resulting from uncontrolled renting of concessions, and the evident loss of control by the GFC over the State Forests which it is mandated to administer on behalf of the people of Guyana, contributed to the citizens’ petition against the technically weak Forest Bill 2007. Specifically, the petition protested the draft sections 15 and 16 on joint ventures –

‘should have been placed earlier in the structure of the law, grouping eligibility clauses together. It is unclear why the wording of section 16 is so convoluted compared with the much simpler wording in section 15 in the February 2004 version. What is important is the prevention of rentier behaviour (sub-letting) which negates the principle of open tenders and bidding for rights to access publicly-owned assets. This under-the-table consolidation of public assets in foreign hands is nowhere sanctioned in law or policy in Guyana. Section 16 should be entirely simplified and re-written . . .’.

The National Assembly failed to take heed.

Accumulating forest concessions

is contrary to national policy

In addition to the illegalities exposed above, the accumulations of rented logging concessions are contrary to national policy. The 1993 timber concession policy is clear that ‘No additional areas will be granted to TSA holders until they have demonstrated their ability to work existing concessions for maximum sustained yield’ (GFC timber concession policy 1993, page 3). And ‘the grantee shall work the area to the satisfaction of the Commissioner in accordance with the terms of this Agreement’ (Timber Sales Agreement template in the second schedule ‘A’ of the Forest Regulations 1953/1982, clause 6). This clause is reiterated as ‘The concessionaire shall work the area to the satisfaction of the Commissioner in accordance with the terms of the concession agreement and only in accordance with the Forest Management plan, as approved by the Commissioner, . . .’ in the third edition of the GFC Code of Practice for forest operations for Timber Sales Agreement and Wood Cutting License holders (published on the GFC website in mid-2014; clause 6 of the general terms and conditions, annexe 5, page 194).

Neither during the management by the original Guyanese concession holder nor subsequently under Bai Shan Lin have any of these concessions been worked to the maximum sustainable yield. On the nutrient-poor soils which are characteristic of Guyana’s hinterland and based on long-term research by Tropenbos International’s Guyana programme, and from the Edinburgh Centre for Tropical Forestry on contract to Barama in the 1990s, the GFC estimates that commercial timber grows at the rate of about 1/3 m3/ha/year; not the 20 m3/ha/year as the GFC Commissioner repeatedly but perhaps accidentally stated at his Press conference on 18 August. The GFC defines that maximum sustainable yield as a harvest not exceeding 20 m3/ha of commercial timber over a period of 60 years, and proportionately reduced for shorter cutting cycles; there are other qualifications in the GFC codes to prevent over-harvesting of individual kinds of timber. For the 25-year cycle commonly associated with the later Timber Sales Agreements, the maximum yield is 8.3 m3/ha and for the 15 years of the original TSA held by Nagasar Sawh the maximum is 5 m3/ha.

The field audits prescribed in the same 1993 policy would have shown that the loggers were not cutting at those intensities, and therefore the concessions were not being worked in accordance with GFC prescriptions, and therefore there were no grounds for adding more concession area by adding more rented TSAs. The under-cutting in overall terms was readily acknowledged and shown in data tables during the presentation by the GFC Commissioner at the Press conference on 18 August.

Thus the illegal renting of Haimorakabra in 2007 has been aggravated by the against-policy additions of other TSAs to the Bai Shan Lin forest empire.

Due diligence checks?

There are only the repeated assertions of the GFC that the awards of forest concessions have been in accordance with law and GFC procedures. The GFC has produced no documentary evidence that the applications for any single logging concession have been subject to due diligence checks prescribed in both the SFP (1993) and SFEP (1999) manuals of procedure for processing applications for forest concessions.

There is one exception: the owner of Simon & Shock International wrote about his experience in ‘Modern milling equipment is the answer, we have undertaken not to export logs if our application is granted’ (Stabroek News, 01 July 2007). That letter referred to a GFC review process, which lasted from at least October 2005 to February 2007 and involving at least six meetings of the GFC Board. After the Board agreed to the issue of SFEP 03/2007 in the upper Essequibo, the Minister took a further eleven months to issue the SFEP in January 2008.

Simon & Shock had run out of money or lost interest in 2009, did not pay the SFEP area fees or submit routine reports, and the GFC reclaimed the 346 Kha SFEP. In the following year, 2010, an Indian high-street coffee retailer, Café Coffee Day, with no known experience of management or harvesting of natural tropical rainforest acquired the SFEP on payment of the outstanding debts of Simon and Shock (more than US$ ¼ million) and a premium of US$600,000. This premium was not used in the forest sector but seized by the Government to help meet liabilities owed to the policyholders of Clico (Guyana) bankrupted in 2010; information then on the GFC website, now disappeared. Initially registering a subsidiary named Dark Forest Company (S) Pte. Ltd., the coffee retailer now trades in Guyana as Vaitarna Holdings Private Inc. (VHPI).

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) usually removes project summaries and environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) proposals and reports rapidly from its website, and does not make such documents available online in an archive. It is not clear that all the TSAs now held under the operational control of Bai Shan Lin were correctly converted from SFEPs with verified inventories, forest management and business plans, or had their financial management status scrutinised. The sketchy and pro-forma proposals currently visible for Bai Shan Lin on the EPA website are so brief and lacking in detail as to be useless as screening tools. The pro-forma proposals for ESIA by BSL are quite remarkably similar to that posted by the EPA for VHPI in January 2011.

Created in 1994 as a Government one-stop-shop for potential investors, Go-Invest should surely be the place to look for documentary evidence of the application of due diligence checks on those investors. Instead, CEO Keith Burrowes told Kaieteur News on 17 August ‘I prefer not to comment on your questions on Bai Shan Lin and considering that only recently I was appointed the CEO of this company, I can assure that I will look into it.’ (‘Bai Shan Lin logging scandal deepens…Bai Shan Lin says in full page ad application took four years to process. GO-INVEST has no application for logging or any related activity – Opposition’, Kaieteur News, 18 August 2014).

Full process for acquiring logging concession not part of VPA legality assurance in Guyana

Guyana must develop an acceptable legality verification scheme as part of its application for a Voluntary Partnership Agreement under the EU Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (EU-FLEGT) action plan 2003. The GFC has elected so far to take a narrow view of what documents should be treated as verifiers that a forest concession holder holds legal logging rights to the forest. The GFC does not include any evidence of independent due diligence checks. Instead, indicator 1.1.1 requires only ‘copy of advertisement [for the forest area], completed application form, GFC’s Technical Committee report, and Cabinet Approval’ and indicator 1.1.2 requires the certificate of taxpayer identification number (TIN) [and/or] business registration.

Note that there is no requirement in law for Cabinet to be involved in award of forest concessions. It is the Commission (GFC) which decides on concession awards, according to sections 6-12 of the Forests Act 2009. This is unlike the preceding law where the President or GFC officers authorised by the President issued the large concessions, the TSAs and SFEPs.

Suspension or cancellation of non-compliant logging concessions

The logic of allowing private renting of forest concessions is unclear. The concessions are awarded with conditions for working the forest. If the State Forest as a public asset is not being managed according to national policy, then logically the concession should be suspended or cancelled, as provided for in the Forest (Miscellaneous provisions) Act 1982, section 11 –

‘Where any condition of any lease made under section 7 or timber sales agreement granted under section 7A is not fulfilled, or where any regulation is not observed, the Minister may by notice to the lessee or grantee of the agreement suspend the lease or agreement whereupon it shall cease to be lawful for the said lessee or grantee of the agreement to carry out any operations on the land subject to the lease or agreement’.

Provision for suspension, amendment or revocation is continued in section 18 of the Forests Act 2009.

The cancellation process has been activated for the Unamco/Case Timbers (TSA 05/1991), Caribbean Resources Ltd. (TSA 04/1989) and several others. The rescinded concessions should have been returned to the pool of unallocated State Forest for a recovery/regeneration period or, if checked by silvicultural rapid assessment and determined to be capable of sustainable management, advertised for public auction ‘in a competitive, fair and transparent manner’. This is the policy as referenced in Part III section 4 of the National Forest Policy 1997/2011 and sections NFP 300 and NFP 320 of the National Forest Plan 2001/2011.

The private rentier transaction, passing operational control of State Forest public assets from the original awardee to a third party without public due diligence checking and premium bidding, is clearly incompatible with good governance. Civil society noted this huge loophole in the Forest Bill 2007 and protested as part of the citizens’ petition in 2007. The protest was ignored and this loophole is now formalized in the joint venture arrangements covered by section 16 in the Forests Act 2009.

The result of this poor legal drafting is that approved national policies and the GFC’s own code of practice for TSAs and WCLs are directly opposed by sections of the Forests Act 2009, much to the benefit of Bai Shan Lin.

The Commissioner and Corporate Secretary of the GFC have claimed that Bai Shan Lin’s forest empire in Guyana has been legally acquired and is operated in accordance with the relevant laws and procedures. The following summary table shows that these claims are at best tenuous and in most cases plain wrong. The Board of Directors of the GFC, the Minister for Natural Resources and the Environment, the Cabinet, the former President as Minister of Forests, and the National Assembly (especially the Natural Resources sectoral committee) all share responsibility for failing to scrutinise and discipline this out-of-control government agency.

Bai Shan Lin now has de facto control over at least one-fifth of all logging and exploratory concessions in Guyana, an area equivalent to 6 per cent of Guyana’s territory. To put this issue in perspective, 80,000 Amerindians hold legal title to 15 per cent of Guyana.