Greater acceptability

It appears from observations that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) might be pondering what it must do to guarantee even better outcomes from its policy prescription for the developing countries that it helps. Periodic statements show that the IMF is satisfied that its policies are being met with greater acceptability among developing countries. It states with greater assurance that its policies are working. No doubt the drive towards the Millennium Development Goals spurred many countries on and over the last 25 years or so, they had become comfortable utilizing the remedies that it prescribed for dealing with their ailing economies. The IMF reported earlier this year that several beneficiary countries had made significant progress in reforming and growing their economies, and had made great strides toward macroeconomic stability. Yet, there is a nagging concern about the restraining effect that poorly functioning national institutions are having on the pace of development in many developing countries. An increasing number of experts are coalescing around the view that a country with poorly run and poorly developed institutions was unlikely to develop at a fast pace, even if it consistently achieves economic growth. This evolving situation threatens to diminish the favourable accomplishments that are identified in some of the following passages.

Looking back at the nineties, the IMF pointed out that the vast majority of low-income countries were in economic distress and required radical, long-term policy changes which had to be accompanied by debt relief or cancellation. It notes that many of these economies are becoming more open and integrated into the global economy with some of them slowly participating in the international capital markets, a major indicator of global acceptability. The economic adjustments have been so successful that many of these countries are also attracting foreign investment, and are nurturing their own private financial sectors. One of the principal tools used was the Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF).

The ESAF is a programme that got started in 1987. It aided countries with struggling economies to make major reforms to their economic structures and institutions with the objective of promoting higher economic growth and external viability in a balanced manner. Guyana was one of those countries that adopted changes like reducing the size of the public sector which led to the privatization of a range of public enterprises and lower public sector employment. It also liberalized foreign trade and the foreign currency market. Guyana also eliminated mechanisms that set artificial prices for agricultural produce.

Cross important hurdle

The IMF was able to tighten programme monitoring and keep a close watch on the performance of countries. At that time too, the entity crossed an important hurdle when it was able to insert itself into the public communication programme of member countries. In a review of the effectiveness of the ESAF in 1999, the Fund became convinced that the success of its programmes could be enhanced if it could be part of the conversation with the general public about its work in country. The approach became more intimate as the Fund assisted governments to explain to society at large the content and rationale for their programmes. This meant that the IMF engaged in more frequent contacts with representatives from civil society and participated in national conferences on policy issues.

The Fund is reported to have increased its contact with groups beyond government in more than 85 per cent of the countries covered at the time. In Guyana, the principal groups that it met with were the business community, non-governmental organizations and the media. Unlike in other countries where it had contact with multiple line ministries, in Guyana, the report showed that in the late 1990s, it dealt only with the Ministry of Health. The IMF also disclosed that it helps government with the dissemination of programme-related information through the media and conferences. This activity has been pursued as part of an effort to get the society at large to take ownership of the reform programmes that were implemented.

Gone are the days when the Fund was thought of as meddlesome and undermining sovereignty. The Fund was often criticized for insisting on conditionalities that were insensitive to the political realities of a country. This insensitivity often led to hardships by already vulnerable groups in society and those near the margins of poverty. Invariably there were all forms of disturbances in reaction to harsh prescriptions of the IMF that put food and other necessities out of reach of larger segments of the population. In an effort to avoid such occurrences in the future, the IMF monitors whether governments have prepared the ground politically to implement whatever structural adjustment programme was agreed. One of the outcomes is that it allows for the use of safety nets to minimize the impact of the adjustment on the poor and vulnerable groups.

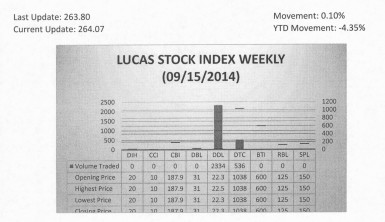

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) increased by 0.1 per cent in light trading in the third period of September 2014. The stocks of two companies were traded with 2,870 shares changing hands. There was one Climber and no Tumblers. The value of the stocks of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) rose 0.9 per cent on the sale of 2,334 shares while those of Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC) remained unchanged on the sale of 576 shares.

Flexibility

Part of the IMF’s success therefore could be attributed to the flexibility that has become a greater component of IMF concessional financing. One such example is the nascent Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust. This is a facility that was created in 2010 with three lending windows with names that reflect a recognition that weak economies cannot always respond in the same way and at the same speed to a crisis as moderately strong or rich countries could. An especially good innovation of the three facilities is the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) which provides flexible programme assistance without programme-based conditionalities whenever the need arises.

Confidence of members

The money to make these facilities work has also been coming in with relative ease and reflects the confidence that member countries have in the operation of the system. It would appear as if the tensions of the past that characterized the relationship between many developing countries and the Fund have disappeared. One consequence of this easing of tensions is a greater willingness on the part of member countries to make financial contributions to the coffers of the Fund. According to the IMF, lending commitments for concessional purposes to low-income countries have been coming in at a satisfactory pace. It noted that money for concessional loans more than doubled from US$1.2 billion in 2008 to US$3.8 billion in 2009 and has been rolling in at an annual average at US$1.6 billion from 2010 to 2013.

The favourability of IMF assistance was also manifested recently in the willingness of members who account for 90 per cent of the windfall from recent gold sales to agree to permit the Fund to use the excess money in its lending programmes. This is clearly evidence that they support the efforts of the IMF in letter and spirit. This money will be used to assist the poorest member countries. The atmosphere in the IMF must be a very good one at this stage and the level of satisfaction among its membership high in light of the recent generosity and extraordinary goodwill that are being exhibited.

Apprehensive

But the IMF remains apprehensive about the sustainability of the positive results and in particular about the ability of beneficiary governments to reduce inequality in their countries, and it might be prepared to ask for the chance to go further in its involvement in national economies to secure the desired outcome. If we look at a country like Guyana, the IMF has the right to worry because it sees a country where a government seems interested in creating highly imperfect institutions which it then appears willing to undermine. For example, it created the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) which it then understaffed and underfunded for nearly four years. During the period, the FIU is accused of bringing one case of money laundering to the office of the Director of Public Prosecution (DPP) for possible action. Of course one should not forget the Integrity Commission which could never get properly constituted, and therefore cannot function. All Guyanese know that the Public Procurement Commission has not even been established.

The recent cases of BaiShanLin and Vaitarna expose the iron rule of oligarchy in Guyana where the Guyana Forestry Commission appears able to ensure that these investors get duty-free concessions that Go-Invest is unaware of. These cases further expose the minimal reliance on checks and balances within the executive itself. While the EPA has imposed restraining operational conditions on BaiShanLin, the GFC is happily allowing it to access and export timber.

Missing the signs

These and similar types of malfunctioning institutions are not pleasing to anyone, but the IMF might be missing these signs in Guyana. Even though there is no economic justification for allowing these institutional weaknesses to persist, the IMF seems rather content to let this government off the hook. For all the help it has given Guyana over the past 20 years, it ought not to be satisfied. It sees Guyana’s consistent low ranking on the Transparency International’s Index and its slippage in other indices, including the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index. Yet, the IMF’s most recent Article IV Consultations failed to drive home the need for the government to do a better job at enabling institutions to function properly and to create those that should be created.