Introduction

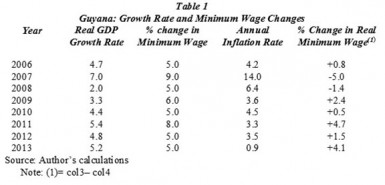

Last week I introduced a Table showing that, over the eight years 2006 to 2013, the average net annual increase in the public sector minimum wage (adjusted for annual inflation) was shockingly low, about one percent. Recall also that the available dataset utilized for this calculation is restricted to those years. That Table contained other important information, which I will explore today; for ease of reference this is reproduced below.

Before addressing the further information there, recall the essential prerequisites put forward to successfully challenge poverty and inequality in Guyana were 1) strong trade unions 2) more class based ideological underpinnings guiding political actors 3) greater public advocacy aimed at raising consciousness and 4) a decisive focus on the minimum wage, a living wage, and job programmes, as the cutting edge of public, private, and civil society endeavours.

The Movement of Wages

The dreadful performance of the real public sector minimum wage revealed is further reinforced by the Table’s indication of a declining share of labour income in total income (GDP). Let me explain.

The dreadful performance of the real public sector minimum wage revealed is further reinforced by the Table’s indication of a declining share of labour income in total income (GDP). Let me explain.

For starters, the public sector minimum wage represented in the Table is not the wage received by all (or even most) public employees. Indeed the wage reported there for 2006 to 2013 did not legally apply to private sector workers, although as indicated going forward from mid-2013 it will apply nationally, assuming compliance and enforcement. Given the country’s large pool of exploited, desperate unorganized and unemployed workers, compliance and enforcement are not assured.

Hopefully, the statement above unambiguously makes clear the public sector minimum wage is not being promoted here as a “representative” national wage. Acknowledging this, I do however believe the annually announced government increases in this wage provides a useful marker for the trend in wage behaviour across the private sector as well. This marker provides the private sector with two useful guideposts. One is that it sets out for a number of private employers as well as their employees an “aspirational target” for bargaining the agreed rate of increase of their annual wages. Second, for a number of other employers it is tempting to follow this increase because it could be put forward, from a human resource management perspective, as reasonable.

Obviously, in practice some cancelling out will occur from among those who receive wage awards above the trend rate of increase in the minimum wage and those who receive less. It would seem reasonable to argue that for Guyana, the trend in overall wage increases across the country is unlikely to be either far above or below the trend in the public sector minimum wage increases.

To emphasize, while the public sector minimum wage is clearly not the wage and salary payment which most employees in Guyana receive as their pay, the trend for increases in this wage may be reasonably taken as being not far removed from the trend rate of their actual pay increases.

If the above proposition holds, then the information in the Table indicates 1) the rate of annual change in the real public sector minimum wage for the period 2006 to 2013 had averaged about one percent 2) this rate was substantially below the rate of increase of real GDP (or simply economic growth), which had averaged about four and one- half percent over the same period and 3) this was quite a substantial difference and would seemingly indicate a falling share of national output going to labour income and therefore rising inequality.

Declining Returns to Labour

This outcome is predicated on a fundamental “theorem” in growth economics, illustrated here. Assume for the sake of simplicity, the real value of total output in Guyana (or its real GDP) is entirely distributed to the two productive factors responsible for producing it. These factors are deemed to be labour and capital as defined below. If this takes place and it is interpreted as above that over the period 2006 to 2013 labour’s share has been declining, then by straightforward inference the share of capital must have been rising.

For present purposes capital is defined in a productivity- related manner. This means it basically represents assets located in Guyana, which generate returns, depending on their productivities. It is therefore a productive factor like labour earning competitive returns based on its productivity. As such capital can take several forms; including 1) physical capital, for example real estate, housing, infrastructure, buildings, farms, machinery and equipment, factories and so forth 2) financial capital, for example stocks, shares, mortgages, bonds and other financial products 3) intangible capital for example proprietary brands, trademarks, patents, licenses, royalties and so forth.

Similarly, labour refers to the physical and mental/intellectual effort, which Guyanese employ in the production of its GDP. Labour would embody skills, training and education and its returns would principally take the form of wages and salaries

Conclusion: sharing the national cake

Because the information presented in the Table suggests the majority of Guyana’s GDP seems to have been distributed in favour of capital, It should be noted all major schools of economic analysis would agree that, based on my assumptions, the outcome suggests a tendency to rising inequality in the shares of the national cake (real GDP) going to capital and labour.

The fundamental distributive workings of the economy favour the haves (that is those depending on returns to capital) rather than the have-nots (that is those depending on returns to labour). This compounds the paltry increases in the absolute real minimum wage over the period 2006 to 2013. Labour is losing bake (good wage increases) and its share of the national cake (absolutely and relatively).

Next week I pursue other related concerns.