By John Lloyd

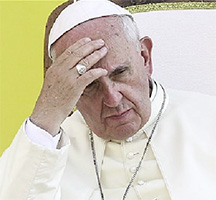

(Reuters) This month, Pope Francis had to come clean.

Time’s Man of the Year for 2013, the object of seemingly universal affection, is a liberal: and that means a season – perhaps a papacy – of struggle. His honeymoon as the Amiable Argentinian is over.

He’s not a simple liberal, to be sure. He believes, in a concrete, physical way, in bodies rising from the dead, and in the existence of the Devil. These are concepts with which evangelical Protestants – in the ascendant in the pope’s native Argentina – are both familiar, and in which they believe. His modern-thinking colleagues quietly squirm.

But he combines, in a way the world hasn’t seen for decades — even centuries — a belief in these manifestations while at the same time being a social liberal. In the Catholic hierarchy, to be a social liberal is to argue that while doctrine is all very well, it has to move with the times. This means recognizing that the times, and many Catholics, are closer to contemporary mores on the family and on sexual behaviour than they are to scriptural fundamentalism.

Thus the expectation, when Francis called the hierarchy of the Church together in Rome in the first half of this month in a synod devoted to the discussion of sex and the family, was that the outcome would be a much-liberalized Church. Catholic gays were especially hopeful of a significant shift, as were groups who want divorce to be made possible under certain conditions. All, when the synod ended last weekend, were disappointed.

The news media, in the main, got it wrong: a fact that the bishops and cardinals, especially the conservatives among them, dwelled on with some venom. They had an excuse: a mid-synod bulletin used language unheard of in the Church before — that gays had ‘gifts and qualities” to offer the Church and that their unions, though they could not be approved, did offer “precious” support. Civil marriages and even cohabitation could be “positive” (though should lead to the commitment of a wedding). It didn’t say that divorcees would be allowed to take communion, but did talk about the need to assist those “damaged” by divorce. Human sympathy was more in evidence than scriptural judgment. The headlines and bulletins heralded a great movement.

But by the end of the synod, the lurch to liberalism had been corrected. The conservatives didn’t win, but they denied victory to the liberals and kept the hierarchy in tension between conservative and liberal positions. At the same time, they came out, more overtly than before, against Francis. This was especially true of the blunt-speaking American Cardinal Raymond Burke, who currently holds the high Vatican position of head of the office of Canon Law — but who expects, because of his opposition to Francis, to be demoted to being Patron of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, a powerless sinecure.

In an interview with Buzzfeed, Burke delivered a sharp warning to Francis of the limits of his powers. He was not, he said, “free to change the church’s teachings with regard to the immorality of homosexual acts or the indissolubility of marriage or any other doctrine of the faith … a change in the Church’s teaching … is impossible.”

With others, Burke has authored a book, Remaining in the Truth of Christ, that laments (as Cardinal Gerhard Mueller put it) “Today’s mentality is largely opposed to the Christian understanding of marriage,” and argues that the Church must resist “pragmatically accommodating the supposedly inevitable.” The conservatives are perfectly aware that contemporary beliefs don’t favor their insistence on doctrine and discipline, but are committed to what they call the Church’s ‘prophetic mission’ — that is, to remain true to the fundamentals because they are God-given, and will be proven right on judgment day.

Their main target is the liberal German Cardinal Walter Kasper, among the most outspoken of the liberals and one said to be close to Francis. (The cardinal has downplayed this, saying that “the pope has read a book by me.”). In an interview he gave to the German daily Die Welt, he said that, though the voting against the liberal positions in the synod was “totally weird,” still the Church would move to soften its attitude to gays. “I am convinced, that in the end we will achieve a wide consensus and make a step towards homosexuals… (they) also have something to contribute in the Church … they are children of God and belong to the family of God.”

These debates have a rich fascination beyond the Catholic community, in part because they mirror more worldly attitudes to homosexuality, which run the gamut through generous acceptance through reluctant acquiescence to strong condemnation. Yet the largest problem for the Church is twofold: first, as it recognizes, many Catholics in the West simply ignore the more severe teachings, or where they are applied, prefer to leave the church than submit.

Second, and more seriously, the modern eye, and the eye of most media see in the synod a gathering of ageing men with no experience of active sexuality (presumably) or marriage, attempting to enforce prohibitions on those who have, and who have developed ways of integrating these troublesome matters into their lives. At the same time, these ageing men did — and still do — have a serious sex scandal within their ranks – one which they have, in the main, dealt with badly.

Cardinal Kasper may be right — that the Church, prompted by its Pope, will open more fully to those it has marginalized for sexual deviance. It’s good that this synod was convened, and that suppressed opinions were aired. But for most, including very many Catholics, it just doesn’t matter. In the old question, of to whom to render the central dilemmas of our lives — to Caesar or God — these issues are subject to neither. For good and ill, they’re up to us, as humans finding, or losing, our way to responsibility.

John Lloyd co-founded the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford, where he is Director of Journalism. Lloyd has written several books, including “What the Media Are Doing to Our Politics” (2004). He is also a contributing editor at FT and the founder of FT Magazine.

Any opinions expressed here are the author’s own.