The Nixon Decision

It is quite possible to contend that the price at which gold is able to trade today is a consequence of the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. On August 15, 1971, the then President of the United States, the late Richard Nixon, decided to suspend the convertibility of the US dollar into gold. That decision brought the Bretton Woods system to a screeching halt, and efforts to revive it came to an end in March 1973.

It is quite possible to contend that the price at which gold is able to trade today is a consequence of the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. On August 15, 1971, the then President of the United States, the late Richard Nixon, decided to suspend the convertibility of the US dollar into gold. That decision brought the Bretton Woods system to a screeching halt, and efforts to revive it came to an end in March 1973.

The decision also put the final nail in the coffin of lingering hopes to bring back the classical gold standard that reigned supreme from 1880 to 1914. The Nixon decision ushered in the era of floating exchange rates as well. Some 43 years later, the effects of the Nixon decision are now permeating the Guyana economy with the price of gold being 2,788 percent higher than it was in 1971 and allowing many Guyanese adventurous enough to brave the harsh forests and terrain to escape the clutches of poverty. One might no doubt wonder about the reason that the Bretton Woods System was created and how could a decision of one person bring it down much to the benefit of a country like Guyana so many years later.

Long March

The long march to favourable gold prices started from Bretton Woods, a town in New Hampshire, where the agreement to set up the

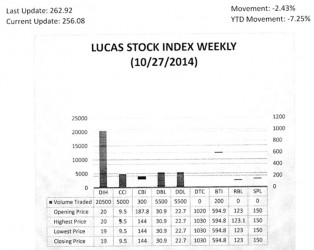

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) dropped 2.43 percent in trading during the final period of October 2014. The stocks of six companies were traded with 37,000 shares changing hands. There were no Climbers and three Tumblers. The value of the stocks of Banks DIH (DIH) fell 5 percent on the sale of 20,500 shares while the value of the stocks of Citizens Bank Incorporated (CBI) fell 23.36 percent on the sale of 300 shares. The value of the shares of Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (BTI) fell 0.02 percent on the trade of 200 shares. In the meanwhile, the value of the shares of Caribbean Container Incorporated (CCI), Demerara Bank Limited (DBL) and Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) remained unchanged on the sale of 5,000; 5,500 and 5,500 shares respectively.

International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (now known as the World Bank) was made.

The purpose of the system was to create confidence in international trade among countries by ensuring that there was sufficient liquidity to finance world trade, countries did not impose restrictions on private citizens to send money out of the country and that there was stability among exchange rates used in international transactions. It did so by fixing the value of the US dollar to the price of gold and allowing other countries to fix the value of their own currencies to that of the US dollar. When desired, countries could exchange their US dollars for gold.

Par Value System

This exchange rate arrangement was referred to as the par value system or fixed exchange rate regime and the US became known as the banker to the world. Some persons described it as the gold exchange standard since limited amounts of foreign currency could be used in composing international reserves.

This situation, in effect, meant that only the US Treasury could determine the price of gold and the price could not move much vis-à-vis the currency of another country unless that country was experiencing severe balance-of-payments disequilibrium. Under the Bretton Woods System, the IMF was given the responsibility of managing the exchange rate arrangement among member countries and there was little room for the price of gold to move without the permission of the IMF unless a country went rogue.

Increasing Pressure

Nothing works to plan and from around 1968, increasing pressure was placed on the price of gold. In the year that President Nixon took the decision, gold was trading at US$40.62 per Troy ounce and US short-term obligations to the world were becoming due faster than it could handle. From 1850 to 1967, the price of gold moved 85 percent, reflecting a situation in which average gold prices moved rather infrequently and extremely slowly. In the 120 years between 1851 and 1971, gold prices moved 114 percent in stark contrast to the rapid price movements of contemporary times. The emphasis on holding gold prices steady derived from the positive economic experiences under the classical gold standard and the disappointing encounters in the years between 1914 and 1939 that could not avert or contain the economic depression of the period and the eventual eruption of the Second World War.

By several accounts, the classical gold standard commenced around 1880 and continued until 1914 when the First World War started. Under the gold standard, there was reportedly remarkable growth in per capita real income. This suggests that it was a period characterized by stable or declining prices and expanding output. The other contribution of the gold standard was to the expansion of international trade. Many writers point out too that capital did not encounter restrictions in its movement and flowed to wherever productivity was highest. In many instances, national policy was subordinated to international interests and international cooperation was thought to be the result of the efficient functioning of the gold standard. Whether caused by the working of the gold standard or not, people spoke fondly of the era in which government intervention was at a minimum and governments themselves obeyed rules of international behaviour.

Economic Dynamics

This era of the gold standard was often compared to the interwar period of 1914 to 1939 which was characterized by frequent currency devaluations, restrictions on the movement of capital and periods of high tariff barriers, and delinquent international behaviour. So after the Second World War and countries were searching for economic stability and ways to prevent future wars, they tried again to recreate the classical gold standard. It was not possible however because global economic dynamics had changed and the US was holding large current account surpluses while the European economies, battered from the Second World War and increasingly losing colonies, had large deficits.

During this period, Guyana was under British rule and did not decide many aspects of its economic policy by itself. By 1971, however, Guyana had been part of the Bretton Woods System for five years as an independent country. The collapse of the global management arrangement of the fixed exchange rate regime meant that countries like Guyana were left without a well calibrated global monetary compass to help with economic decision-making. To make matters worse, the price of oil, a principal driver of the world economy, rose sharply at the same time and left many countries in economic ruin and the IMF scrambling to find solutions to the financial imbalances that were emerging. The US dollar was valued around G$2.40 at the time and the IMF was gathering its own thoughts about its future role in the international monetary system. The IMF therefore did not present the rest of the international community with any measure of confidence that it could actually help developing countries like Guyana whose problems kept multiplying with each increase in the price of oil.

Collapse of System

The collapse of the Bretton Woods System also meant that gold as a commodity was within its own right to trade at whatever price the market determined. The rise in average annual prices started slowly, rising 137 percent from 1971 to 1973 and accelerated by 528 percent by 1980. Though it could not sustain the relatively high price of 1980, gold remained well over 900 percent of its 1971 price during the 1980s. Gold prices remained tempered during the 1990s up until 2007 when it began a round of sustained upward movements. During the period of the 1980s, production responded slowly to the price movements, averaging about 15,000 ounces annually. However, production has shifted gears and has averaged 326,000 ounces in the last eight years, nearly 22 times more than the output of the 1980s. The industry now employs well over 12,000 persons on a full time equivalent basis and has become increasingly dependent on mechanization to extract the mineral. This change in the production process is expected to intensify as larger foreign players get involved further in the industry.

Transformation

The transformation of the industry has also seen a transformation of its impact on the national economy. Gold output accounts for over 75 percent of output of the extractive industry. The revenue received from gold sales amounted to an annual average of G$66 billion, peaking in 2012 at G$109 billion. This change in outcome arose from both the increase in output and prices for the precious metal. Output grew at an annual average of 13 percent while prices exhibited a 21 percent growth from 2007 to 2011. As a result, gold accounts for a very large share of the total foreign earnings of Guyana.

But the positive effects of gold must be tempered by the significant decline in the value of the Guyana dollar, the inadequate amount of value-added shown by the industry and the possible impact on deforestation and the country’s ecosystem. In 1971, G$2.40 was worth US$1. Today, the exchange rate is G$208.44 to US$1, signaling that the Guyana dollar lost 100 percent of its value from 1971 to present. Despite the 2,888 percent surge in gold prices, Guyana was still unable to recover all of the foreign exchange value that it lost since 1971. Further, with prices as high as they are, industry representatives believe that more gold is being sold than is being converted into jewelry. Furthermore, the higher prices for gold make it harder for many Guyanese on their current level of income to purchase gold jewelry on the same scale and frequency as in the past. The likelihood exists that goldsmiths are not doing too well.

Use Money Wisely

It has taken a long time for Guyana to obtain benefits from an industry that has long received the attention of the entire world community. Gold has been involved in the personal and economic lives of people since its discovery as a store of value and medium of exchange. Freeing it from its restrictive role in the monetary system has made it possible for countries that possess the metal to take advantage of what this natural capital can do for them. Guyana must now decide to use money earned from gold wisely to take care of its current and future population. That also means taking care of its environment and ecosystems for the time will come when the flow of income would be commercially insignificant.