Reggae fi Radni

(to the memory of Walter Rodney)

yu no si how de cloud

dem jus come satta pan mi dream

like a daak silk screen

owevah di vizshan I ad seen

di vizshan I ad seen

di vizshan I ad seen

some may say dat Waltah Radni

woz a victim af hate

some wi she dat him gaan

through heaven’s gate

some wi she dat Waltah Radni

shoodn tek-up history weight

an go carry it pan him back

like him did wear him anarack

but look how di cloud

dem jus come satta pan mi dream

sit upon mi dream

like a shout ar a scream

a shout ar a scream [. . .]

Linton Kwesi Johnson

Liesence fi Kill

Sometime mi tink mi co-workah crazy

di way kristeen woodah gwaan jokey-jokey

den a nex time now a no-nonsense stance

di way she wine-dung di place laas krismus dance

di way she love fi taak conspirahcy

mi an kristeen inna di canteen a taak

bout did et a black people inna custody

how nat a cat mek meow ar a dyam daag baak

how nohbady high-up inna society

can awfah explaneashan nar remedy

wen kristeen nit-up her brow

like seh a rhow she agoh rhow

screw –up her face

like she a trace she agoh trace

hear her now:

yu tink a jus hem-high-five an James Ban

an polece an solja owevah nawt highalan wan

wen it come to black people Winstan

some polece inna Inglan got liesense fi kill

well notn Kristeen she surprise me still

but hear mi now:

whey u mean Kristeen

a who tell yu dat

a mussi waan idiat

yu cyan prove dat

a who tell mi fig oh she dat

Kristeen kiss her teet

an she cut mi wid her yeye

an shi she yu waan proof

yu cyan awsk Clinton McCurbin

bout him hafixiashan

an yu cyan awsk Joy Gardner

bout her sufficaeshan

yu cyan awsk Colin Roach

if him really shoot himself

an yu cyan awsk Vincent Graham

if a him stab himself

but yu can awsk di Commishinah

bout di liesense fi kill

awsk Sir Paul Condon

bout di liesense fi kill [. . .]

yu fi awsk Maggi Tatcha

bout di liesense fi kill

yu can awsk Jan Mayja

bout di liesense fi kill

yu fi awsk Mykal Howad

bout di liesense fi kill

an yu can awsk Jak Straw

bout di rule af law

yu fi awsk Tony Blare

if him is aware ar if him care

bout di liesense fi kill

dat plenty polece feel dem gat [. . .]

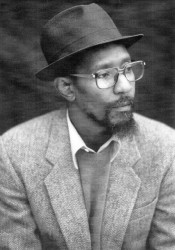

Linton Kwesi Johnson is very prominent in the United Kingdom in literature and performance. He is the leading dub poet in Britain, very celebrated, in demand, highly recognized and established among English poets generally. His entry into this hallowed company came early – in 1975 while he was a student at Goldsmith’s College, University of London when dub poetry itself was just on the rise in Europe. He was one of its pioneers and took his place very quickly, foremost among Jamaican poets performing in this genre.

He was born in Jamaica but went to London at age eleven to join his mother who had migrated. He grew up in the British society that he has so incisively criticised in verse, but the verse in which he became most proficient is a form that originated in Jamaica around 1970, grounded in the rhythms of reggae and Jamaican culture, a performance-oriented poetry heavily influenced by the music, by the DJ tradition and oral poetry. Yet it is a scribal craft that works on the page like any literary work as effectively as it does on the stage.

Dub poetry emerged during the significant cultural upheaval in Jamaica (and to a lesser extent across the Caribbean, especially Trinidad) between 1968 and 1970 following the wave of protests, reactions and responses to the expulsion by Prime Minister Hugh Shearer of Walter Rodney from Jamaica. Many currents were running, including Black Power, Rastafari, African consciousness, political consciousness, protest poetry, grassroots theatrical and literary outreach, poetry readings in Yard Theatre (unconventional venues). This was accompanied by the growing influence of Creole poetry, the use of Creole and a strong sense of orality and oral qualities in Standard English poetry.

Leading mainstream poets were involved in this – prominent among them being Mervyn Morris, Kamau Brathwaite and Dennis Scott, who performed in the Yards.

Their poetry is known to include much of these performance driven oral qualities, dread talk and creole language. At the same time a new group was emerging which began writing what came to be called dub poetry, first recognised by the journal Savacou on the UWI, Mona Campus which published the first collection of it in the 1970-71 issue. Following this was the rise of Linton Kwesi Johnson in England, Alan Mutabaruka, Mikey Smith, Orlando Wong and Jean Breeze.

Before long this form of poetry was well established and publications began to appear both in book form and as sound recordings. This new development was acknowledged by the publication of Voiceprint by Longmans (1979) edited by Stewart Brown, Gordon Rohlehr and Mervyn Morris. Brown commented that Caribbean poetry included what was in books but just as much incorporated what was on “the cassette tape”.

Johnson has been involved in those developments from the release of his ‘Sonny’s Lettah’, a very early work, performed with instrumental back-up to very famous pieces like ‘Reggae fi Radni’, ‘Reggae fi Dada’ and later work like ‘Liesense fi Kill’. He is quite versatile, with a range of poems including many that are not of the ‘dub’ variety. In Guyana, one of the very outstanding works done by the National Dance Company is by Vivienne Daniel which is danced to a reading with a reggae musical accompaniment of Martin Carter’s ‘Poems of Shape and Motion’. The voice on the recording is that of Johnson.

‘Reggae fi Radni’ was written in the 1980s dedicated to the memory of Walter Rodney and demonstrates excellently how Johnson’s poetry works on the page. Its literary qualities are taut and include the way the images/metaphors serve the mood of the poem and the state of mind of the persona. At the same time the poem contains an oral quality that includes its rhythm and its occasional echoing repetitions. He has learnt to write creole (Jamaican ‘patois’) in neat crisp phrases that flow fluently with an orthography that is easy to read. The poem stands as one of the memorable works out of the several written for Rodney. Although in circulation since the 1980s it is here published in a recent collection Selected Poems (Penguin, 2006) which was featured at the Caribbean Poetry Project Conference at University of Cambridge in September 2012.

‘Liesense fi Kill’ is more recent and an even more remarkable poem, written in the nineties and published in the same collection. It is in the tradition of dub poetry, which, for a long time was protest poetry, very radical in political outlook and rooted in a Jamaican proletarian sub-culture. Johnson carried the form very famously in London and this is a British poem, one of many in which he interrogates English society. In the same tradition of sounding a voice for the oppressed, the dispossessed and unprivileged he engages social wrongs.

Note the dramatic neatness of the verses – the poem is a dialogue with choral commentary complete with irony and skilful characterisation. Kristeen (most likely Christine) is a careful study in which the persona observes and reveals her (unlikely) political consciousness and keen sense of social injustice. She speaks up against the treatment of the ‘Other’ in British society which betrays her characteristic “jokey-jokey” exterior, “winin dung di place” at a party or her apparent craziness. One who might easily be not taken seriously, even to the point of talking about “conspiracy”.

Johnson turns that incorrect superficial image on its head with a telling closing irony in which her conspiracy theories are endorsed by the persona not as conspiracy fantasies, but as the truth.