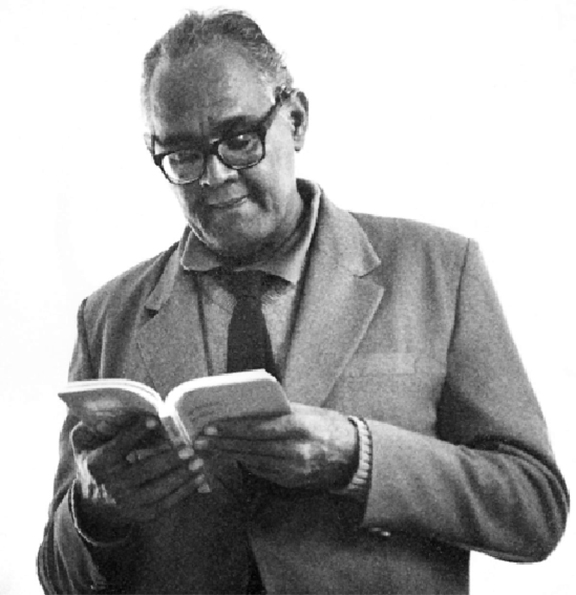

“When the people began to display their young vigour, Carter turned his attention to nurturing the forces of the radiant future.” So heralds Sydney King in his introduction to the London edition of Poems of Resistance from British Guiana published by the left-wing publishers, Lawrence and Wishart in 1954. Reading Martin Carter’s work as a direct expression of the mood and experiences of anti-colonialism in Guyana, King (now Eusi Kwayana), hoped that this poetry could be part of “sustaining the people in their struggle.” Although the collection ran to three editions between 1954 and 1978, you will be very lucky to see a copy of Poems of Resistance nowadays. A second-hand copy of the 1954 edition is rare and recent UK and US bookseller prices range from G$17,740 to G$33,940. While the poems from this collection have been reprinted in new Carter collections and anthologies over the years, on the 60th anniversary of the publication of this short incendiary collection of 18 poems, we should ask how well do we know this major landmark in Guyanese literary history.

In the preface to the 1964 second edition of the collection (abbreviated to Poems of Resistance) Neville Dawes wrote “the poems collected here may be regarded in one way as a single poem of resistance to the special oppression of 1953, one eloquent refusal to be dehumanised by imperialist bayonets and colonial prisons.” It is this collection that contains some of Carter’s most famous poems, ‘University of Hunger’, ‘This is the Dark Time My Love’ and ‘I Come from the Nigger Yard’. Certainly the London edition was explicitly linked to the political events at the time; at the end of the collection a letter was addressed to the ‘Reader’, informing him or her that “the author of these poems and four other members of the People’s Progressive Party in British Guiana were arrested and kept under detention for over two months without charges being instituted against them and without being brought to trial for any offence alleged to have been committed by them.” Donations were requested for the “Guiana Defence Fund” in order to establish legal representation for the men. The collection of poems becomes a medium for disseminating news of the political events in the colony, and for raising money. Although the anti-colonial goals of the PPP are not mentioned explicitly in this letter, Carter’s imprisonment is proof that Carter, the poet, and Carter, the political activist, share the same task: to offer resistance from British Guiana.

Lawrence and Wishart were clearly interested in the political situation in Guyana. Carter joined a publishing list that already included Cheddi Jagan’s Forbidden Freedom. When the collection was advertised in the 1954 catalogue, the publishers closed the gap further between the poems and the political events: “Martin Carter, the foremost poet of the Caribbean people, is a true people’s leader. A Minister in the democratically elected government of British Guiana, he was arrested when the Constitution was suppressed. Several of these poems were written in prison.” Some of the details are wrong (Carter was never a minister in a PPP government) and some offer intriguing puzzles: which poems were written in prison and how should we read these resistance poems?

To complicate matters further, there is not just one version of Poems of Resistance. By 1954 there were multiple versions of the collection in circulation around the world. Six anonymously written poems were seized by the police from the Magnet Printery in Georgetown shortly after Carter was arrested in October 1953, and these were sent to the Colonial Office in London. We must not underestimate the risks involved: Carter’s wife, Phyllis, and Janet Jagan arranged the publication of these six poems at a time when PPP literature was being seized and books confiscated from the homes of PPP members. The poems – ‘I Will Not Still My Voice’, ‘This Is the Dark Time My Love’, ‘Shines the Beauty of My Darling’, ‘Tomorrow and the World’, ‘Let Freedom Wake Him’ and ‘I Clench My Fist’ – were steadfast in their aim for a new kind of life.

To complicate matters further, there is not just one version of Poems of Resistance. By 1954 there were multiple versions of the collection in circulation around the world. Six anonymously written poems were seized by the police from the Magnet Printery in Georgetown shortly after Carter was arrested in October 1953, and these were sent to the Colonial Office in London. We must not underestimate the risks involved: Carter’s wife, Phyllis, and Janet Jagan arranged the publication of these six poems at a time when PPP literature was being seized and books confiscated from the homes of PPP members. The poems – ‘I Will Not Still My Voice’, ‘This Is the Dark Time My Love’, ‘Shines the Beauty of My Darling’, ‘Tomorrow and the World’, ‘Let Freedom Wake Him’ and ‘I Clench My Fist’ – were steadfast in their aim for a new kind of life.

For a while civil servants worried that the poems had been written by a senior civil servant, A J Seymour, but quickly realised that it was Carter, a well-known and therefore in some ways less threatening radical. But we should not rush to see these as poems written in prison. Half of them had been published before in The Hill of Fire Glows Red, and there were only four days between Carter’s arrest and the seizure of the poems. It is possible that the previously unpublished ‘Let Freedom Wake Him’, ‘I Clench My Fist’ and ‘This Is The Dark Time My Love’ were written in prison but there is no archive to help us prove this. Remembering these rebellious days, Phyllis Carter thought she could have smuggled these out, but she also remembered how difficult it was to discover where her husband was imprisoned and could not remember when she first saw him, so there is no evidence and nobody knows for sure any more. In ‘Let Freedom Wake Him’ Carter writes: “It is only the fury of my heart changing to scorn / At the sight of a soldier searching for me.” This discussion of ‘a soldier’ probably dates the composition between 8 and 25 October 1953, the period between the arrival of British soldiers and Carter’s arrest. However, what is most likely is that this anonymous, partial document, with no front cover is all that remains of the first version of Poems of Resistance.

Another publication titled ‘Poems of Resistance’ includes the same six poems and appeared later in 1953 in the left-wing US journal, Masses & Mainstream. These were sent to the journal by PPP Secretary and champion of Carter’s work, Janet Jagan, and published while Carter was imprisoned. There is a further undated pamphlet, titled ‘Poems of Resistance’, held in the National Library, Georgetown. It is a single sheet stating on its cover ‘Poems of Resistance by Martin Carter’, and includes only three poems: ‘Shines the Beauty of My Darling’, ‘Tomorrow and the World’ and ‘I Clinch My Fist’. Speaking recently (2014) about his memories of the period, Eric Huntley, another key member of the PPP, sheds more light on publishing Carter’s work. He was asked by Cheddi Jagan to take a typescript, titled Poems of Resistance, to the printer at the hospital in New Amsterdam. This would have been a government printery and as Huntley notes, the events say a lot about the individual printer who was “willing to take a chance” to help circulate these forbidden poems.

Once you start looking it becomes clear that the reach of Poems of Resistance was wide, involving a diverse network of publishers and readers. A further undated pamphlet published by the Education Department of the West Indian Independence Party of Trinidad is held in the New Beacon archives at the George Padmore Institute in London. This pamphlet is titled, I Sing My Song of Freedom – Poems of Resistance. It includes as a foreword a long quotation from Thomas Paine encouraging resistance in another time and place: “These are the times that try men’s souls … But he that stands NOW deserves the love and thanks of men and women.” Slightly misquoted, Paine’s 1819 work is re-presented for the contemporary moment, pressing for action in another time of crisis. So by the time Lawrence & Wishart – the publishing arm of the British Communist Party – published its Poems of Resistance from British Guiana, Carter’s urgent political poems were already making their way around the world.

Once you start looking it becomes clear that the reach of Poems of Resistance was wide, involving a diverse network of publishers and readers. A further undated pamphlet published by the Education Department of the West Indian Independence Party of Trinidad is held in the New Beacon archives at the George Padmore Institute in London. This pamphlet is titled, I Sing My Song of Freedom – Poems of Resistance. It includes as a foreword a long quotation from Thomas Paine encouraging resistance in another time and place: “These are the times that try men’s souls … But he that stands NOW deserves the love and thanks of men and women.” Slightly misquoted, Paine’s 1819 work is re-presented for the contemporary moment, pressing for action in another time of crisis. So by the time Lawrence & Wishart – the publishing arm of the British Communist Party – published its Poems of Resistance from British Guiana, Carter’s urgent political poems were already making their way around the world.

What is so interesting about these differing publications of the same poems is the map they create and web of relationships they suggest. Carter’s poems plot an international map of anti-colonialism, one which travels within Guyana and to the USA, to Trinidad, to the Colonial Office in the UK, and to supporters of the British Communist Party. We could guess by reading the poems that Carter’s work would circulate in this way, but it is also possible to reconstruct some of the journeys it did make. In a poem which contains the concluding words “although you point your gun straight at my heart / I clench my fist above my head! I sing my song of freedom,” its poetic achievement is strengthened by its ability to travel and agitate among different groups of readers and audiences. In ‘I Clench my Fist’ Carter does not just write about singing his song of freedom, his poem is that song. ‘Song’ then takes on a renewed sense of meaning, reminding us of oral traditions of protest and also helping us to recognise how this poetry connected people. When the Emergency in Guyana was announced in October 1953 the West Indian Independence Party held demonstrations in Woodford Square in Port of Spain, Trinidad. It’s very likely that Carter’s poetry was recited at these public demonstrations – certainly WIIP member, John La Rose, remembers reciting Carter’s work during the 1950s.

To discover that Carter’s poem-songs circulated through the Caribbean, America and Britain is one way to map their success. These discoveries, however, raise more questions about publishing and Carter’s readers than we can answer. What we have is the skeleton of a literary history, but still many gaps to fill in about who was reading Carter in this period and how his work entered the world.

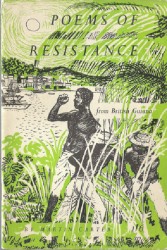

One intriguing aspect to the London edition of Poems of Resistance from British Guiana is its illustrated cover. The unattributed artwork is monochrome with block prints of green that suggest sugar cane and vegetation, but also energy fields swirling out from the sun. In the foreground stands a male sugar worker with a raised fist. Next to him are his labouring comrades and in the distance ships that echo not only the ships that would transport sugar from the colonies but also at this tense moment the arrival of British troops on warships to control the Emergency. The raised fist reminds us of Carter’s poem of anti-colonial rebellion and The Communist Manifesto’s rallying cry “Workers of the world, unite.”

And how might readers have viewed this image? I think it would depend on how well they knew Carter and the crisis taking place in Guyana. It would certainly have reminded some readers that Carter had been arrested at Plantation Blairmont and that there was strong PPP support within agricultural communities. For some it would have registered that this middle-class poet was extending his poetic voice to the workers whose life he hadn’t lived – that he was extending his voice to the Afro-Guyanese and the Indo-Guyanese workers who worked on the plantations in the past and present. For some the cover probably seemed like a portrait of the poet.

But Poems of Resistance from British Guiana does not offer a portrait of the poet, or at least it does not offer only this. The collection and its various editions offer a portrait of a people struggling to claim a place for themselves in the world. In his poem ‘I Come From The Nigger Yard’ Carter writes with the fervour of ‘negritude’, reclaiming racial identity in order to politicise life:

It is me the nigger boy turning to manhood

Linking my fingers, welding my flesh to freedom.

I come from the nigger yard of yesterday

leaping from the oppressor’s hate

and the scorn of myself.

In Carter’s violent image of welding “flesh to freedom” and the front cover’s insistently raised fist, we can track an important politicization of black identity. The poem combines Frantz Fanon’s recognition and censure of the objectification of blackness: the poet cannot ignore his imposed ‘nigger boy’ and ‘nigger yard’ identity. However, the energy and activity of the verbs – linking, welding, and leaping – are also suggestive of Fanon’s revolutionary dream: “to come lithe and young into the world that was ours.” When we look at the front cover again we see in the man with his raised fist both the colonial objectification that Fanon is so troubled by and the dream of liberation.

Furthermore, the man and his fellow workers are threshold figures that we must contemplate as we open and close this slim collection. The anonymous man stands against oppression, from the determinedly local site of ‘British Guiana’, but as Carter’s work reminds us this locality is not isolated from the rest of the world. The final lines of the 1954 edition read:

Like a web

is spun the pattern

all are involved!

all are consumed!

As the emerging publishing history of Poems of Resistance shows us, Carter’s insistently local work was leaping out from Guyana to reach a diverse global audience, both near and far. We may never be able to tell the complete story of how Carter was published and read in the 1950s, but (to use Rupert Roopnaraine’s poetic words) we can appreciate now more than ever Carter’s place in “the web of October.”