Dear Editor,

The governing Santa agency has published a clause in its agenda to make its annual year-end retrospective payout to what are called ‘public servants’, which leaves opportunity for the GRA to collect extra income in December not totally unanticipated.

The familiar repetition of this imposition on the ‘public’ reflects their perceived status as ‘servants’, not to mention an arrogance towards (if not ignorance of) the real substance of compensation management.

Reproduced in the Annual Estimates (2014) are bona fide categories of public servants distributed over fourteen job grades. These are –

- i) Administrative

- ii) Senior Technical

iii) Other Technical & Craft Skilled

- iv) Clerical & Other Support

- v) Semi-skilled Operatives & Unskilled

The 14-grade job structure must by now be about three decades old, and has been progressively honoured in the breach. Not only have the 14 salary bands been rendered meaningless by the simplistic application of across-the-board increases, but also the system has been polluted by the exponential use of the device of recruiting persons on a contract basis, and ignoring relevant scales in the process.

So that in the last decade or more the category of ‘contracted employees’ has been formally added to those mentioned above.

Perhaps the more fundamental implication is the absence of a much needed job evaluation exercise to take account of the varying values of new jobs that several new technologies have created in the last two decades. The absence of any such central direction is compounded by the freedom (or licence) with which individual agencies can and do have to employ ‘contracted employees’ amongst others, thus increasingly rendering the Public Service Commission, for example, quite irrelevant of its purpose.

The practice of employing contracted employees is so pervasive that it is not identifiable in the official Estimates at which level of employment the recruits are placed. Once again the 14-grade job structure becomes irrelevant. It is overtaken by the application of the theory of relativity, that is, looking after one’s relatives (and friends).

Amongst the myriad other significant defects in this perjured exercise is the flagrant non-recognition of the different levels of productivity over a specific work period, so that the across-the-board imposition makes no distinction between those who perform beyond the call of duty, and the regular absentee office assistant. This constitutes a level of insensitivity that invites the strongest condemnation.

There is therefore none of the traditional performance incremental reward, measureable against specific job descriptions, if at all they exist. The result of the imposition is merely the adjustment of the minima and maxima of scales that are in fact not utilised. Consequently those public servants who were recruited at the minimum of a scale of ten years ago would be earning exactly the same salary as the recruit in 2014 – at the minimum.Space does not provide opportunity to amplify on other fault lines, so that it is most inadequate to observe this travesty of justice as just a ‘freck’ as pronounced by one politician, clearly admitting a lack of appreciation of the scale of the inequity and iniquity of the issue.

But for the time being public servants, their employers, and their clients at large, need to be reminded of the virtual deconstruction of the public service through the recruitment of ‘contracted employees’, who are not necessarily constrained by the maximum of a given salary scale, but on the other hand benefit from receipt of a gratuity (non-taxable) in lieu of pension of 22.5% of basic salary payable every six months. This adds up to an increase of 45% on annual salary.

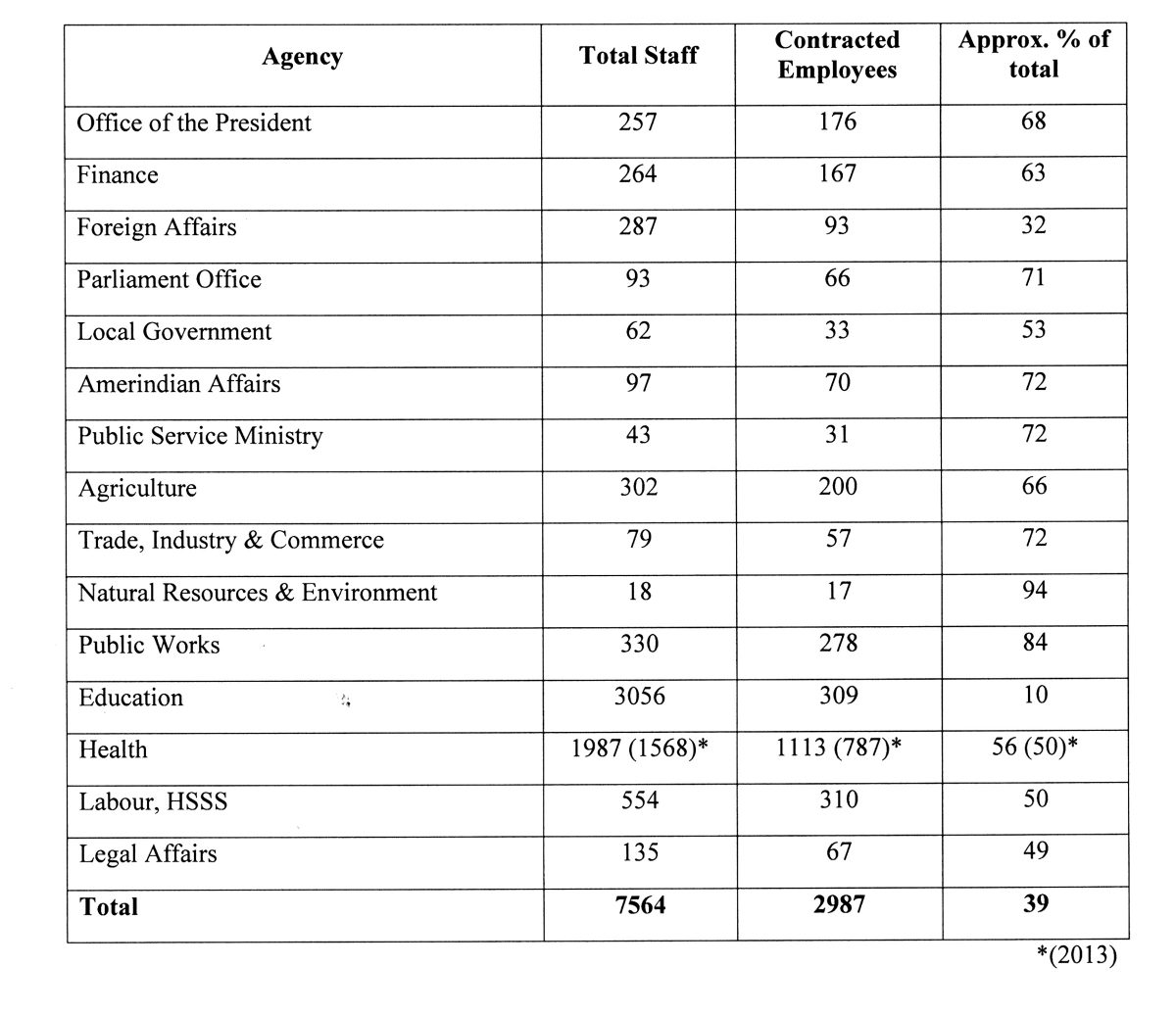

Some numbers may help to put the problem in starker perspective. For example the following should speak for themselves:

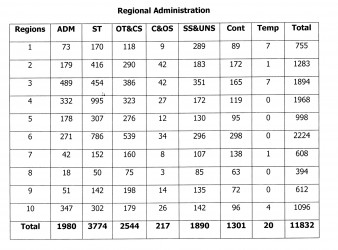

Obviously a few agencies like GPHC, Gecom, the Supreme Court and others have been omitted; while the Regional Administration deserves separate and more detailed attention, if only to reflect the wide scope of authority delegated to the regions in the area of recruitment.

What has been reflected is a significant, if not yet complete deconstruction of the ‘public service’ as once known. It is now a muddled mismanagement of human resources understood by few, if any; one that has palpably failed to keep the pious undertakings given during more than one elaborate overseas consultancy to professionalise a modern public service that would be productive and satisfy normal organisational management expectations.

Yours faithfully,

E B John