Democracy and accountability are the twin sides of the same coin. Democracy facilitates accountability which in turn facilitates development. A lack of democracy results in a lack of accountability which in turn stagnates development.

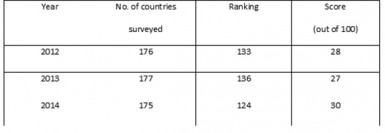

Three major events took place on the anti-corruption front in the last few days. The first was the release of Transparency International’s 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) which placed Guyana at 124 out of 175 countries surveyed, with a score of 30 out of 100. This represents a slight improvement over 2013, when Guyana scored 27 from 136 out of 177 countries. However, we still continue to occupy the position of the second lowest in the Caribbean, Haiti being the lowest with a score of 19.

The second event was the observance of International Anti-Corruption Day on 9 December. It was 11 years ago on this day that the United Nations Anti-Corruption Convention came into being. Guyana acceded to the Convention on 16 April 2008. The local transparency body, Transparency Institute Guyana Inc., marked the occasion with its second annual march from Umana Yana to Parliament Buildings and well as with its third annual fundraising dinner.

The third event was a joint statement from six Caribbean countries – The Bahamas, Barbados, Haiti, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago – emphasizing the Region’s commitment to transparency and integrity at a meeting of Ministers of economy and finance held on 5 December in Miami, also to mark International Anti-Corruption Day. It is unfortunate that Guyana was not one of the signatories, and it is unclear whether our Minister of Finance attended the meeting.

2014 Corruption Perceptions Index

Corruption is the misuse or abuse of public power for private gain, and in so doing, the public interest is sacrificed in favour of private interest. Given the opaque nature of corruption, it is not possible to measure actual levels of corruption in a country. It was for this reason that the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) was developed in 1995 to measure perceived levels of corruption in the public sector. The CPI is calculated based on surveys carried out of the perceptions of knowledgeable people, such as senior businessmen and political country analysts, about levels of corruption. For the 2014 CPI, twelve data sources were used, including the Economist Intelligence Unit, the World Bank and the World Economic Forum.

5Most of the countries surveyed regard the CPI as an authoritative pronouncement as the best substitute measure for actual levels of corruption. Those who share a deep concern for good governance, transparency and accountability view the index as an important measure in any fight against corruption. An improvement in the CPI score and ranking is an indicator of a reduction in the level of corruption. The first step therefore is for a country to accept in good faith the CPI score and ranking; recognize that corruption exists and the extent to which it is perceived to be so, and taken appropriate measures to bring about an improvement in its score and ranking.

5Most of the countries surveyed regard the CPI as an authoritative pronouncement as the best substitute measure for actual levels of corruption. Those who share a deep concern for good governance, transparency and accountability view the index as an important measure in any fight against corruption. An improvement in the CPI score and ranking is an indicator of a reduction in the level of corruption. The first step therefore is for a country to accept in good faith the CPI score and ranking; recognize that corruption exists and the extent to which it is perceived to be so, and taken appropriate measures to bring about an improvement in its score and ranking.

In releasing the 2014, Chairman of Transparency International, Mr. José Ugaz, stated that the index shows that economic growth is undermined and efforts to stop corruption fade when leaders and high level officials abuse power to appropriate public funds for personal gain. He further stated that:

Corrupt officials smuggle ill-gotten assets into safe havens through offshore companies with absolute impunity…Countries at the bottom need to adopt radical anti-corruption measures in favour of their people. Countries at the top of the index should make sure they don’t export corrupt practices to underdeveloped countries.

Grand corruption in big economies not only blocks basic human rights for the poorest but also creates governance problems and instability. Fast-growing economies whose governments refuse to be transparent and tolerate corruption, create a culture of impunity in which corruption thrives.

The CPI and Guyana

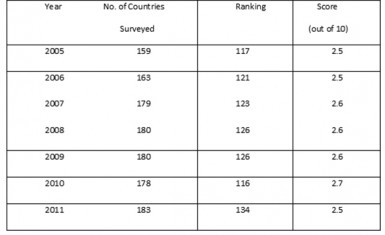

Since 2005, Transparency International has included Guyana in the CPI assessment. Table I shows Guyana’s ranking and score prior to 2012, using an earlier

methodology and scoring system whereby countries were rated on a scale of 0 to 10. In 2012, the methodology and scoring system changed. Countries are now ranked on a score of 0 to 100. The results for Guyana are shown at Table II.

Table I

Guyana’s Ranking and Score on the CPI (2005-2011)

Table II

Guyana’s Ranking and Score on the CPI (2012-2014)

As can be noted, there has been no noticeable improvement in our standing during the last ten years, despite several reform initiatives that took place over the years. These include:

Establishment of the Integrity Commission in 1997 to provide for the annual declarations of income, and assets and liabilities of Ministers of the Government, Members of Parliament and senior public officials;

Introduction of Programme Budgeting in 1998 which is a form of results-based budgeting aimed at strengthening the budget process. The emphasis is accountability for outputs, outcomes and impacts rather than for inputs – a kind of value-for-money approach;

Creation of the Guyana Revenue Authority (GRA) in 2000 to give it greater autonomy and flexibility in the assessment and collection of public revenues, without government interference;

Amendment to the Constitution to provide for, among others, the establishment of the Public Procurement Commission to ensure greater competition, transparency, fairness and equity in the procurement of goods and services and in the execution of works;

Passing of the Procurement Act in 2003 to give effect to the constitutional provision, and to provide for a detailed set of rules for public procurement, codified in the form of legislation;

Passing of the Fiscal Management and Accountability (FMA) Act in 2003 to strengthen the management of and accountability for public resources;

Introduction of the Integrated Financial Management and Accountability System (IFMAS) in 2004 to keep abreast in the use of information technology;

Passing of the Audit Act in 2004 to strengthen the independence of the Auditor General, to provide for greater autonomy and flexibility in the conduct of public audits and in reporting the results, and to provide for oversight role of the Audit Office by the Public Accounts Committee; and

Passing of the Access to Information Act in 2011 to provide citizens to reasonable access to government’s programmes and activities.

Assessment of the reform initiatives

Most of the reform initiatives outlined above, although laudable, were not voluntary acts on our part, freely and consciously given out of a concern to improve our governance and accountability arrangements. Rather, they were conditionalities set by the international financial institutions for access to much-needed loans and grants. These institutions recognized the weaknesses in our system of governance and accountability, out of concern have insisted that we effect improvements, and have provided the necessary funding to do so.

However, we have, by and large, squandered the opportunity to translate these initiatives into real benefits. The reason is simple. Accountability is enriched if it is voluntarily given rather than being imposed. Imposed accountability, regardless of how worthwhile it may be, is likely to result in minimum compliance. If a person does not believe in undertaking a particular course of action but is forced to follow it because of the carrot and stick approach, as soon as backs are turned he/she reverts to the status quo. This is a sad reality with which we are faced. We have collectively failed the Nation in our attempts to own up to these initiatives and to enthusiastically embrace them as champions. There is no denying that we have very good laws on governance and accountability, comparable to international best practice. However, we give lukewarm attention to their implementation, and in many cases we fail to uphold them, especially when they do not serve our purpose.

We are all aware of the non-functioning Integrity Commission where in the absence of a Chairman, no meetings of the Commission can be convened to scrutinize the returns that have been submitted. This is a retrograde step in our fight against corruption. It is public knowledge that several senior public officials flaunt unexplained wealth with impunity.

The Public Procurement Commission is yet to be established despite the lapse of 13 years because of the refusal of the Cabinet to surrender its role to the Commission. Under the watch of the Cabinet, there is evidence of contracts being awarded to individuals and firms without the requisite experience, defective work being performed, undue delays in executing the works, overpayment to contractors and suppliers, and the failure to secure performance bonds to guard against unsatisfactory performance. We have also seen how the pre-qualifications procedures for the supply of drugs and medical supplies were biased in favour of a particular supplier.

Programme Budgeting is given cosmetic treatment in the presentation of the National Budget, and two of the important modules of IFMAS – procurement and asset accounting – are yet to be implemented. In addition, despite the passage of the Access to Information Act and the appointment of a Commissioner of Information, the service is not utilized in any meaningful way. There was evidence of on at least two occasions where access to information was denied on very flimsy grounds.

Finally, for a variety of reasons, the Audit Office is hamstrung in terms its ability to deliver the level of service consistent with its role as the watchdog of public accountability.