“This is the final chess column to run in The New York Times” – Statement carried in the NYT on October 11, 2014 at the conclusion of an article by chess columnist, Dylan Loeb McClain.

When it was published, that terse statement came as a surprise to the chess world, especially for those aficionados who had grown accustomed to seeing the column as a weekend staple. The announcement by the Times elicited a number of comments; some enthusiasts naturally argued for the column’s continuation , while others demonstrated a quiet indifference.

Among the numerous reactions was a thoughtful article in Slate Magazine by Matt Gaffney, who wrote: “As a format, the weekly chess column is archaic, yet another in the infinitely long list of things rendered obsolete by the internet.” Obviously, Gaffney has a point here. Times have changed. Major tournaments are currently live-streamed and anyone with a laptop computer can access information about tournaments readily. We can tune in for the analyses and opinions of grandmasters while the games are in progress. There is more readily available information about the chess world that could possibly be digested.

But, according to Gaffney, the newspaper chess column has not been quite put to rest as yet. He speculates on what a relevant, interesting, weekly column could possibly look like, and lists three essential characteristics.

But, according to Gaffney, the newspaper chess column has not been quite put to rest as yet. He speculates on what a relevant, interesting, weekly column could possibly look like, and lists three essential characteristics.

- It must be written by someone who is deeply involved in the chess world.

- They have to be world-class players either past or present – most likely past, since you won’t find too many active top players willing to spend playing and preparation time writing a weekly column for a general audience.

- The person needs to be an engaging writer, highly opinionated and preferably, a bit of a character.

Gaffney expressed the view that the Times could either shutter the column altogether, or hire one of two distinguished English-language chess columnists, namely, Lubomir Kavalek or Nigel Short, a duo who boast a fine record of excellence in chess playing the game and in writing. Kavalek is a 71-year-old Czechoslovakia-born US grandmaster and a world class player of the 1960s and 1970s, who wrote a dazzling chess column for the Washington Post from 1986 to 2010. Currently, his chess column resides at the Huffington Post. Kavalek has been known to take unexpected and fascinating dives into chess history. Short is a 49-year-old English grandmaster who was ranked No 3 in the chess world during the late 1980s . He was Garry Kasparov’s challenger for the world championship title in 1993. Short crafted an enormously entertaining chess column for the Sunday Telegraph for a decade.

In countries wherever chess is played on a large scale, columnists are part of a distinct and respected group. For one thing, columnists are few, and vacancies, frankly, do not exist. McClain, the former Times columnist, was not a grandmaster. He peaked at 2300-plus but wrote some enjoyable columns.

He defeated a few grandmaster contenders for the job, most likely with his background as a journalist and his independence. McClain noted that he is beholden to no one in a story which was published on Chess Base. He pointed out: “The chess world is rife with conflicts of interest. Many people who might otherwise be qualified to write about chess with authority, have past or current business relationships with people or organizations they might, or would have to write about, or they are friends with those people. That makes them impossible to be unbiased or objective.”

It is refreshing to learn, however , that the die has not yet been cast in relation to the continuation of the chess column. Spokeswoman for the Times, Danielle Rhoades Ha explained as follows: “A final decision for the column [on all platforms] has not been made yet.” At present, chess is still being carried in the Times, albeit by Ben Greenman , an accomplished author.

Chess games

The following games were featured in the rapid section of the 2014 London Chess Classic tournament which was played from December 6-7. Grandmaster Hikaru Nakamura of the United States won the tournament ahead of Italy’s Fabiano Caruana and India’s Vishy Anand.

Caruana v Nakamura

White: Fabiano Caruana

Black: Hikaru Nakamura

- e4 c5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 e6 4. O-O Nge7 5. d4 cxd4 6. Nxd4 Ng6 7. Be2 Bc5 8. Nb3 Bb6 9. c4 d6 10. Nc3 a6 11. Kh1 e5 12. Nd5 Ba7 13. Bg4 O-O 14. Bxc8 Rxc8 15. Be3 Bxe3 16. Nxe3

Nge7 17. Rc1 a5 18. c5 dxc5 19. Nxc5 Nd4 20. Qd3 Qd6 21. Nb3 a4 22. Nxd4 Qxd4 23. Qb1 Qd2 24. Rcd1 Qb4 25. Rd7 Nc6 26. a3 Qb3 27. Rd3 Qb6 28. Nd5 Qb5 29. Rc1 Rcd8 30. b4 Nd4 31. Rc5 Qe8 32. Qd1 f5 33. exf5 Rxf5 34. f3 Rf8 35. Nc3 b6 36. Rc7 b5 37. Rc5 Rc8 38. Ne4 Rxc5 39. Nxc5 Qf7 40. h3 Qf5 41. Re3 h6 42. Qd2 Rd8 43. Re4 Kh7 44. Qf2 Rd5 45. Kh2 Nb3 46. Nxb3 axb3 47. Qe3 b2 48. Qe1 Rd4 0-1.

Hebden v Anand

White: Mark Hebden

Black: Viswanathan Anand

- d4 d5 2. Nf3 Nf6 3. e3 c5 4. c4 cxd4 5. exd4 g6 6. Nc3 Bg7 7. cxd5 Nxd5 8. Bc4 Nxc3 9. bxc3 Qc7 10. Qb3 O-O 11. O-O Nc6 12. Be2 Be6 13. Qa3 Rac8 14. Rb1 Rfd8 15. Be3 Na5 16. Rfc1 Nc4 17. Bxc4 Bxc4 18. Qxa7 Bd5 19. Qb6 Bxa2 20. Qxc7 Rxc7 21. Rb6 Rdc8 22. Bd2 Bd5 23. Ne5 e6 24. f3 Ra8 25. Nd3 Ra2 26. Rb2 Ra3 27. Nc5 e5 28. Rb4 exd4 29. cxd4 b6 30. Re1 f5 31. Bf4 Rca7 32. Bd6 bxc5 33. Bxc5 Ra1 34. Rxa1 Rxa1+ 35. Kf2 Kf7 36. h4 Bf6 0-1.

Giri v Kramnik

White: Anish Giri

Black: Vladimir Kramnik

- e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Nc3 Nf6 4. h3 Bb4 5. Bd3 O-O 6. O-O d6 7. a3 Bxc3 8. dxc3 Ne7 9. a4 h6 10. a5 Ng6 11. c4 Be6 12. Be3 Nd7 13. b4 Nf4 14. Re1 Qf6 15. Bf1 g5 16. Kh2 Kh8 17. g3 Nxh3 18. Bxh3 g4 19. Bg2 gxf3 20. Bxf3 Bxc4 21. Kg2 Kg7 22. Rh1 Rh8 23. Rh4 Nf8 24. Qd2 Ne6 25. Qc3 Bb5 26. Rah1 Kf8 27. Bg4 Bc6 28. Bxe6 Qxe6 29. b5 Bxb5 30. Rxh6 Rxh6 31. Rxh6 Qg4 32. f3 Qg7 33. Qxc7 a6 34. Qxd6+ Kg8 35. Rh5 1-0.

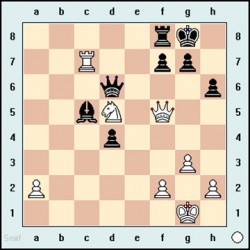

Chess puzzle

Hikaru Nakamura v Sergey Karjakin, Cuervanaca, 2004

White to play and win

Solution to last week’s chess puzzle

White played: Rxe5 if Qxe5 Bxh7+