Dear Editor,

More than a decade ago the Government of Guyana undertook an imaginative initiative to modernise the public sector in general and more specifically the public service. A massive donor-funded consultancy was contracted to guide the process. Indeed as a result of extensive discussion a vision was developed and expressed as follows:

“Within ten years, the Guyana Public Service will be a customer driven institution providing quality services for the economic stability and sustained development of Guyana through the twenty-first century. The Public Service will be small, comparatively well paid, efficient and effective, undertaking planning, supervisory and regulatory functions, facilitating and encouraging investment and the private sector, and operating within sustainable cost limits related to national economic performance.

“In the wider public sector, agencies must be setup and operated efficiently and effectively according to clearly established procedures. The government in its regulatory capacity will ensure this.”

“In the wider public sector, agencies must be setup and operated efficiently and effectively according to clearly established procedures. The government in its regulatory capacity will ensure this.”

In a consultancy report of May 2002, the Minister for Public Service was quoted as follows:

“No longer can the public sector function in the old traditional mode. This new era will require a more flexible institution and the emphasis must be on the strategic approaches to planning. The reformed public sector therefore must be infused with new values, a higher sense of mission and purpose, and be totally conceptualised with a spirit of new professionalism.

“The reform should focus on people, organisational processes and structures.”

The study identified five cornerstones on which to modernise Guyana’s public sector management, namely:

- i) strengthen policy development and coordination;

- ii) build performance monitoring and evaluation structure;

iii) establish a new human resources management infrastructure;

- iv) develop a management framework for arm’s length agencies and strengthen their accountability;

- v) foster transparency and integrity of the public sector.

A three-stage approach towards modernising the human resources capacity was proposed:

-To develop a solid human resources management strategy.

-Focus on putting in place human resources’ management policies and practices.

-Focus on capacity building and institutionalising a results-based performance management and incentive system.

It is against this background and more that a number of factors need to be taken into account, including the institutions and methodologies being utilised in measuring the achievement of the vaunted development of human capital.

While the relevance of the quoted vision to reality would be a matter of conjecture, one could only deal with certain facts, examples of which are discussed below:

The Public Service Ministry (PSM) itself had to be revamped in order to become responsible for implementing a human resource management and development programme.

Additionally the Public Service Rules were to be updated – a project in fact undertaken by another consultancy some years after the initial recommendations on modernisation. As it turned out the PSM, which was to be the pivotal agency in the change process, has since been miniaturised, as if no one else in authority had read, or heeded, the consultants’ critical recommendations, many of which emerged out of intensive discussions with representatives of all the operational agencies.

Additionally the Public Service Rules were to be updated – a project in fact undertaken by another consultancy some years after the initial recommendations on modernisation. As it turned out the PSM, which was to be the pivotal agency in the change process, has since been miniaturised, as if no one else in authority had read, or heeded, the consultants’ critical recommendations, many of which emerged out of intensive discussions with representatives of all the operational agencies.

The capacity of the PSM has since been severely decimated, with staffing of 52 in 2012 reduced to 31 in 2013.

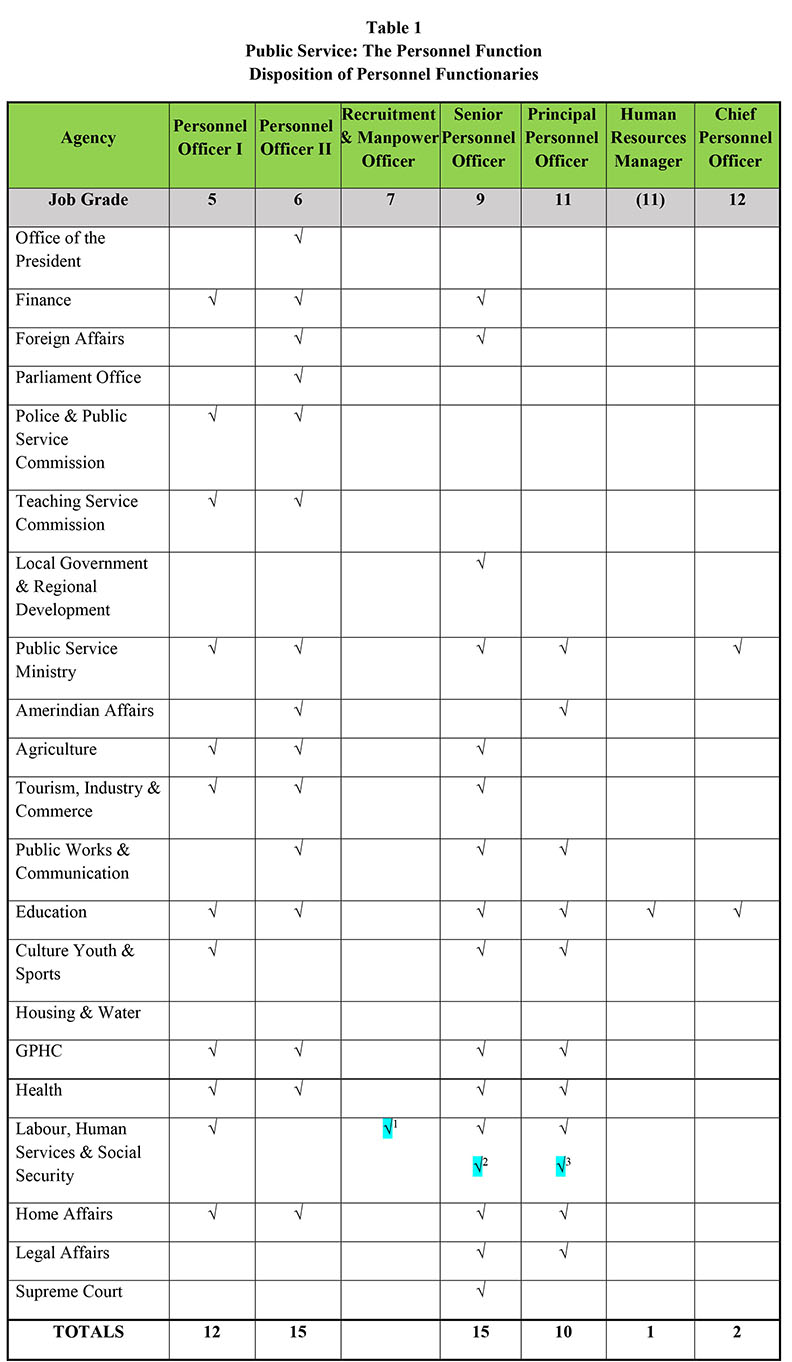

In the meantime there has been no attempt to institutionalise any policies and practices of human resource management and development. To date the National Estimates still refer to ‘Personnel Officers’ – in the following order of seniority: Chief Personnel Officer; Principal Personnel Officer; Senior Personnel Officer; Personnel Officer II; Personnel Officer I. By some rare decision there is also in the PSM a Junior Human Resources Officer. Note there is a Human Resources Manager in the Ministry of Education That apart, what the above explicitly indicates is that one can grow over a period of years from the lowest to the highest grade of ‘Personnel Officer’ (not unusually) in the same agency, since account is taken more of familiarity with the extant environment, rather than of relevant specialist qualifications.

For what it is worth the following Table 1 offers a view of the disposition of ‘Personnel’ functionaries in the Public Service (2013).

1 Recruitment & Manpower Officer

2 Senior Recruitment & Manpower

Officer

3 Chief Recruitment & Manpower

Officer

(Not included in Totals)

Of relevance must be the role of the Public Service Commission (PSC). Originally established to control, direct and monitor the consistency with which levels of recruitment, transfers and promotions, and disciplinary actions are effected, many of these responsibilities have been deliberately devolved to the various public service agencies over the years. The situation can be described as having depreciated to the extent that the PSC has almost become irrelevant.

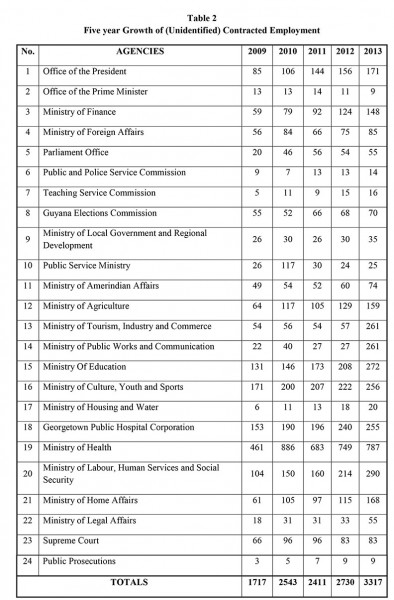

For example the PSC has no control over the exponentially increasing recruitment of ‘contracted employees,’ a practice which fundamentally counters the myth of developing human capital.

Hopefully Table 2 below showing the disproportionate growth of ‘contracted employees’ in the traditional public service, may be of interest.

But to revert briefly to the incapacity of the PSC, one can point to the high incidence of acting appointments (some two and more grades above the substantive posts) which have continued for several years.

There is the egregious example where in one legal agency (since reorganised) the acting incumbency of more than a decade as Deputy Head remains overlooked for confirmation.

Meanwhile it has to be noted that in the (traditional) public service there is a position titled Regional Executive Officer – in charge of each of the ten regional administrations, but not shown in the National Estimates. The incumbents are all political appointees, and it would be exceptional for the Deputy REO (an established position in the public service) to be promoted to that higher level.

This is one of the more outstanding contradictions of the development of human capital in the public sector. The truth is that there is no comprehensive strategy, no grand succession planning, according to which human capital in the public sector can be meaningfully developed, in the face of clear predilection for unidentified ‘contracted employees.’

The teaching service

Arguably the foundation of any course for human development must be education. In Guyana the public education system is the subject of much debate, with the uncertainty surrounding its efficacy resulting in a burgeoning private education sub-sector.

Nevertheless there is much annual cheer for the comparatively limited number of successes, matched by an eloquent silence regarding the substantial proportion of failures.

Part of this problem in early human resources development has to do not only with the quantity of teachers in the system, and importantly the hostile environment with which they must cope, but moreso with the poor compensation paid for the statutory requirement of appropriate qualifications, and the demand to achieve work targets on a timely basis.

The truth is that by comparison with many in the public service who graduate in their careers essentially by years of service, and whose performance is not evaluated, while being virtually assured of annual increases, the agents of early development of human capital are substantially cheated.

The compensation structure which reflects the job structure in the teaching service is archaic, thanks partly to the ineptitude of the representative union. There are 20 (putative) job grades as compared to 14 in the public service. One only has to be at Grade 10 in the public service to match the TSC’s Grade 19. Above that the respective positions of Principal of Queen’s College and the Cyril Potter College of Education are assigned a fixed salary. This grade is described as ‘Special.’

The differentiations between the salary structure in the teaching profession and that of public servants within the very Ministry of Education are too numerous to mention. Suffice it to say that they are substantially at the disadvantage of the former.

For example the differential in bandwidth (ie, between minimum and maximum of a scale) defies credulity. At 2013 say, in the case of the TSC the bandwidth ranged from 4.63% in the lowest scale to 11.45%. This compares with a bandwidth of 12.36% at the lowest and 39.85% at the highest in the PSC salary structure.

It is difficult to contemplate movement within the TSC scales, almost as if there were no intention to do so, given the rigid conditionalities which apply.

What needs clarification is the concept of being promoted, for example, from Pupil Teacher to Temporary Unqualified Master. And there are also such permanent positions as Temporary Qualified Master of different grades. There is the further conundrum in which non-graduate and graduate masters can carry the same level of responsibilities for significant differentials in pay. In short the structure abounds in confusion. There is a crying need for a comprehensive overhaul (including a job evaluation exercise) of an institution that is so critical to the development of human capital needed in our society, or else the several hundred vacancies that are advertised annually will never be filled.

Yours faithfully,

E B John