By Kathryn Cramer Brownell

(Reuters) – “Saturday Night Live” celebrates its 40th anniversary today, saluting the late-night comedy programme’s rich history with a three-hour show. But SNL is remarkable for more than its longevity, ratings and impressive list of comedians who began their TV careers as one of its Not Ready for Primetime Players.

Since its first season, “SNL” has lampooned the American presidency in ways that conflated distinctions between entertainment and politics. From Chevy Chase’s bumbling pratfalls as President Gerald R Ford to Tina Fey’s verbal pratfalls as Sarah Palin, the comic impersonations did more than just make viewers laugh. Unlike the political satire of Will Rogers, Johnny Carson or even CBS’s controversial The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, “SNL” sketches helped transform the US president into an “entertainer-in-chief.”

The comic personas that “Saturday Night Live” created have shaped news narratives and even subsumed actual political achievements in the public eye.

Watching comedians play out a president’s foibles and follies each week, viewers have also come to expect their politicians to lead by entertainment. The programme amplified the importance of ‘showbiz’ in modern politics. Its influence pushed many political hopefuls to appear on comedy shows and build their voting base. By expanding the audience for political comedy, “Saturday Night Live” helped usher in an age in which Jon Stewart’s “The Daily Show” could be regarded as a key source of news information.

Watergate. Vietnam. Stag-flation. The year that “Saturday Night Live” started, 1975, was filled with frustration, anger and disappointment — a time ripe to launch a comedy show. The live comedy-sketch show capitalized on younger viewers’ distrust of all aspects of the ‘establishment’, from corporations to the military to the White House.

During the first season, Chevy Chase quickly broke out as a star of the ensemble by playing a dimwitted and clumsy Ford. Tripping down steps, spilling water, even stapling himself in the head, Chase gained fame and fortune — for himself and the show — by satirizing the president. No previous show or comedian had personally targeted a sitting president with such derision.

By the next year, SNL’s skyrocketing popularity made it increasingly difficult for Ford to neutralize this “bumbler” persona. He had initially felt going on any late night comedy show would be undignified. But he agreed to have his press secretary Ron Nessen serve as a guest host. Ford even put in an appearance during the programme with pre-taped clips from the Oval Office.

Nessen and Ford seemed somewhat awkward participants on a cutting-edge, live-television show. Yet Nessen’s appearance gave the programme political credibility. It also established a strong connection between presidential politics and SNL that has expanded the audience —and intensified the demand — for political entertainment.

Over the past 40 years, presidential hopefuls, Cabinet secretaries, senators and representatives have hoped to reverse Ford’s electoral misfortunes by laughing alongside their comedic impersonators, inviting them to White House dinners or even appearing as guests on their shows.

Though these politicians may have attempted to co-opt “Saturday Night Live’s” satire, this proved difficult. From Dana Carvey’s impersonation of George H W Bush to Will Farrell’s “Janet Reno’s Dance Party” sequence to the 2012 GOP “Sing-along,” “SNL” sketches created defining political tropes that frequently overshadowed elected officials’ accomplishments.

Ford’s comic persona as a klutz, for example, shaped a national narrative of his “accidental presidency” — despite Ford’s distinguished congressional career and collegiate athletic prowess. Darrell Hammond’s uncanny depiction of Al Gore’s 2000 presidential debate performances generated a public conversation about the vice president’s stiff pompousness.

Tina Fey’s impersonation of GOP vice presidential nominee Palin’s loopy ignorance evolved into serious obstacles on the campaign trail.

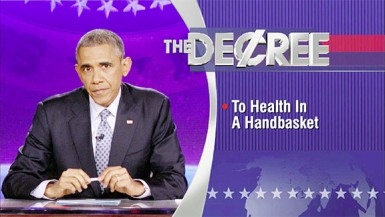

Others, like President Barack Obama, have learned to use political comedy to promote policies and reach new voters. Like President Bill Clinton before him, Obama has flourished in the role of entertainer-in-chief, heightening expectations for his successors to do as well.

Obama sat down with Zach Galifanaki on “Between Two Ferns”, a widely popular Internet show, to discuss the Affordable Care Act. Obama’s recent appearance on the “Colbert Report” displayed his humour as he confronted, and then dismantled, criticisms of his presidency — frequently created by Colbert.

“You have been taking shots at my job,” Obama told the Comedy Central host, “I’ve decided to take a shot at yours.” He then took the host’s chair. “How hard can this be?”

Ford might have answered, “very hard” as he struggled to reassert the “dignity of the presidency” despite Chase’s effective satire.

But this job as entertainer-in-chief has grown easier for politicians because the qualifications for the Oval Office have gone from backroom political negotiations to television tryouts, with fans frequently casting votes for their favourite performer.

The first episode of “SNL” aired on October 11, 1975. But celebrating the history of the television programme in the middle of awards season and right before Presidents’ Day is appropriate. “SNL” has continued to make the entertainment industry relevant politically while providing a platform for political candidates to expand the reach of their message to younger voters, many of whom share the 1970s attitudes of cynicism and distrust.

The irony: “SNL” succeeded by appealing to viewers who distrusted the establishment in 1975. Today, this alternative style of political engagement has become institutionalized in modern politics, while also helping to bring younger voters to the polls.

The question remains: Do they vote for the person or the comic persona?