The practice of producing plays on the public stage for the benefit of CXC study is back. Wole Soyinka’s The Lion and the Jewel has just been performed at the Theatre Guild and preparations have begun for Julius Caesar to be staged in April.

Dramatist Godfrey Naughton, who has been foremost in producing the CXC plays and has directed such dramas as August Wilson’s Fences and Trevor Rhone’s Old Story Time, was responsible for The Lion and The Jewel at the Guild. He worked with Kefa Smith as Lakunle and Mosa Telford as Sidi very enthusiastically supported by Candacy Baveghems as Sadiku, Clinton Duncan and Godfrey Naughton as Baruka and Kim Fernandes as Ailatu. There was further energetic support from the Bishops’ High School performing arts class who provided a chorus of villagers. There is added significance in this inclusion, since Andrew Kendall, a lecturer at the National School of Theatre Arts and Drama, has given new life to drama at his school with the introduction of the CXC subject at CAPE and ordinary levels.

Naughton’s team succeeded in achieving the overall purpose of bringing the drama to life on stage to clarify the script and make it more meaningful for those who have to study it. This happened very much on stage with this production which made a very significant mark with its quite robust acting performances and its set. The play is a comedy very much in the African tradition and these performances very sharply brought out the humour, the dramatic situation and the characterisation. There was creditable attempt to place it in its Nigerian setting with performance style and atmosphere.

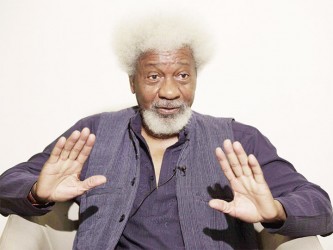

The Lion and The Jewel, first produced in Nigeria in 1959 and published by Oxford in 1962, is not one of Soyinka’s best or most outstanding plays, but it has its fair share of importance and historical significance. It is one of his early plays written in his developing career when African literature was beginning to make its mark on the world stage, in England, in France and in the west. It is a Yoruba play, but written in English and took a prominent place in the forward march of plays, poetry and fiction from West and East Africa in both Commonwealth Literature and the Negritude movement of Francophone origins.

Soyinka, the first black winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, was very much at the centre of those developments in the 1950s and 1960s along with Léopold Sédar Senghor, Aimé Césaire, Léon Damas, Chinua Achebe, Amos Tutuola, Kofi Awoonor Williams and Ama Ata Aidoo, et al. Now writing in English (in some cases, French as well) and widely published, these writers were creating the African Literature that gained in importance and examined, sometimes questioned, African societies and traditional cultures. This was what developed as a part of Commonwealth Literature, but gained an identity of its own and was later to contribute significantly to post-colonial literature along with the works from India and the West Indies as they developed in the United Kingdom.

In terms of drama, Soyinka and Aidoo were foremost in the interrogation of their cultures as they came into contact with colonialism and western society. Aidoo followed Soyinka in this, emerging in 1964 with Dilemma of A Ghost (published 1965). Soyinka began his explorations of cultural dilemmas with Lion and was to further these examinations in greater depths with later plays. Lion is a fairly short play but despite its minor status it is the work of a genius, has a place as an important pioneering drama, and treats cultural conflicts with a good deal of humour.

It is set in a Nigerian Yoruba village still steeped in its traditional way of life but skirting on the edge of modern development and the intrusion of western culture. Eager to see the onrush of this English ‘civilisation’ is the village school teacher Lakunle who has little patience for what he regards as savagery in the traditional customs. On the other side is Baruka, the Bale or traditional Chief enjoying the perks of his office, his dozens of wives and concubines, who has no intention of allowing this to change. He represents tradition and consciously blocks ‘modern’ development from entering the village. Soyinka dramatises this conflict further by having these protagonists not only at opposite political poles, but in competition for marrying Sidi, the “jewel”, the prize. These are symbols and metaphors in the play. Baruka is “the lion”, the powerful, strong, crafty/cunning monarch of the community – the other symbol/metaphor used in the play’s title.

Yet other large issues and conflicts were made very clear in the performance as the battle of gender and the battle of egos and strong personalities were played out, representing the rich complexities in the way Soyinka crafted the struggle between tradition and modernity. Kefa Smith portrayed the zeal and arrogance, the boasts of Lakunle who also came over humorously as really fighting with the modern ways because he wanted to marry Sidi without paying the bride price that the tradition demanded. On the other hand, both Duncan and Naughton played effectively, the ego of the Bale, in his ostentatious shows of prowess, boasting of his conquests in wrestling and new wives.

On the other side, Mosa Telford led the women in their own displays of egoism. She moved easily and with telling virtuosity from the village maiden protesting the insults of her betrothed Lakunle and the proud independent woman refusing the luring entrapments of the powerful Chief, to the taunting temptress ridiculing him when she thought he was impotent. But the high point of Telford’s spirited, graded performance was the very important show of vanity and conceit that became her downfall. She was thoroughly flattered by the appearance of her pictures in the Lagos magazine that filled her with pride and arrogance of her own. Soyinka mixes vices with virtues in the many ironies that he introduces in the play within the battle of gender.

Candacy Baveghems joined Telford in this. The loyal Head Wife of Baruka very believably became the overjoyed and vengeful champion of womanhood in her supposed triumph over her husband’s failure. Baveghems exhibited the fine skills in portrayal of the woman who pretended loyalty while sacrificing to Ogun to wreak revenge over patriarchy. She was convincing in spite of the little and insufficient effort made to age her. Even Kimberly Fernandes in the minor role of the “favourite wife” of Baroka came in very effectively and with humour on the gender war as she too rebels against the tradition of her husband continually taking new wives.

However, all these several combatants are defeated by the wily craft of the old Baruka who proves his potency all round. He outwits Sadiku, tricks Sidi and shows Lakunle that he is no match for him even in the area of intellect, which is supposed to be the teacher’s strong suit. The ironies continue because Soyinka does not even give a neat victory of tradition over western cultural intrusion. The play laughs at the way all the modern advancements and technology, the might of womanhood and the superficial new fashion are no match for the native wisdom of the old chief. The audience has a laugh but is left a bit unsure whether the playwright is supporting traditional patriarchy over justice for women.

Both Baveghems and Smith handle with dexterity the extended battle waged on behalf of women by Sadiku against Lakunle. Their exchanges are reminiscent of the bawdy verbal confrontations between the Greek soldiers and the women in Aristophanes’ Lysistrata. Soyinka was, in fact, more than a bit influenced by the Greek. They also mastered the language, with Telford joining them in the way they captured the Nigerian speech within their stride. Both Naughton and Duncan were also tutored in fluent delivery of it although it occasionally interfered with their clarity.

While Smith was generally strong one wonders why he was made to dance to a song “Love Me for What I Am” by Lobo. Both song and dance were quite out of style with the rhythm of the play and its setting and seemed something just dropped in. Contrarily, where traditional styles and rhythm worked, there was not enough attention paid to choreography in the dances of the chorus and a wrestling match which was too static and lacking in violence when Duncan played it.

Naughton seemed to have taken the time to research the play, but did so to the point of taking some techniques in the use of the chorus with details right out of Wikipedia. The theme song used in the play also did not quite fit, and although impressively well sung by Kimberly Fernandes, also seemed dropped in for a lengthy sequence at the end. One had to wonder about how it fitted, particularly since it is not a Yoruba song.

But the production overall was efficiently directed on a set that was appropriately designed and thoroughly used. The acting was strong all round and there was energy and clarity in the performance. As a production aimed at bringing Soyinka’s comedy to life it worked very well.