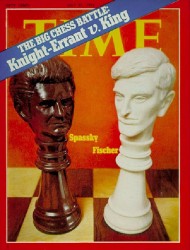

During the ‘Match’ following word that chess was categorized as another exciting version of the widespread draughts and which was delivered by a curious soldier of the former British empire who saw active service in the realm of the outer world, Mr Gomes, our village became a hub which was fired with a fervour for a board game which had not been noticeable in the past. For two months we discussed, argued about a game we knew nothing of, and generally engaged in nonsensical tidbits of news from afar. That vigorous event of 1972, the Spassky-Fischer chess match, became my initial virtual involvement with the rich ancient game.

Fischer’s impact on the game of chess has proven to be phenomenal. He designed a chess clock that complements a player’s time which has been adopted worldwide. He introduced the concept of Random Chess, where a player places the pieces in whichever positions he desires, and plays the game from there. He also promoted the idea that chess tournaments do not accurately determine the strength of a player and only a match would do so. And Fischer’s charisma altered the game in many ways. Before his match with Spassky, chess players were treated trivially. When Spassky won the title in 1969, he was paid US$2,000 for his efforts. Fischer changed that. In 1972, Fischer agreed to a purse of US$250, 000, in addition to thousands in endorsements. Also, it was Fischer who introduced the concept of elite chess players being paid appearance fees.

It was after Fischer that a new breed of chess hopefuls thrived intellectually on the game in Guyana and I was among them. Devoted parents, in my case my grandmother and grandfather, encouraged their progeny to pattern themselves after Fischer. Suddenly, one of the ways to secure wealth and fame in America was to become a great chess player. Naturally, this was not so. It was make-believe, a world of fantasy. In time, we realized we were not anywhere close to Fischer, and so our dreams came crashing down. For myself, however, chess remains a lifelong fulfillment of my spirit.

It was after Fischer that a new breed of chess hopefuls thrived intellectually on the game in Guyana and I was among them. Devoted parents, in my case my grandmother and grandfather, encouraged their progeny to pattern themselves after Fischer. Suddenly, one of the ways to secure wealth and fame in America was to become a great chess player. Naturally, this was not so. It was make-believe, a world of fantasy. In time, we realized we were not anywhere close to Fischer, and so our dreams came crashing down. For myself, however, chess remains a lifelong fulfillment of my spirit.

We continue with the Anatoly Karpov – Irwin Fisk interview:

AK: When I played my match with Korchnoi in 1978, I received only 20% of my prize.

IF: 80% went to the state?

AK: Yes, Spassky received 100%.

IF: So that hurt chess players from then on.

AK: Before Spassky lost to Fischer, and two years after, we didn’t give any money [to the state] from our prizes. From exhibitions, yes, but not from prizes. I was the biggest victim in 1978. We had good money in the Philippines, but I had to give most of my prize to the state.

IF: Did they call it a tax?

AK: No, actually it wasn’t a direct tax. We had to give it to the Sports Ministry. They called it participation in developing sport and chess in the country.

IF: Didn’t Spassky move to France?

AK: Yes, he moved to France in ’75. This was described when the leaders said, “This is enough. We gave chess players everything and they didn’t behave well.”

IF: At that point, did you know who would become the challenger?

AK: No, first I played in the Interzonal Tournament in Leningrad which was much stronger than its counterpart in Brazil. It became clear after the quarter finals that we had qualified already Spassky, Petrosian, Korchnoi and myself. I beat Spassky in the second match.

In the second match, the semi-finals, I lost the first game to Spassky, so this was the most difficult match for me. He wanted to play another match with Fischer, so he prepared quite well. When you lose the first game with white against Spassky, this is not a good start. But, then I started playing very well. I think I played my best match against Spassky. I won convincingly. I faced Korchnoi in the finals, who I beat. Before that Korchnoi had won his match against Petrosian.

We played in the Chess Olympiads in Nice, so this was not only important for chess but also for chess politics. If you remember, Fischer sent an ultimatum to the congress that was taking place in Nice during the Olympiads. I remember in this congress that I made a speech on behalf of myself and Korchnoi, because at that moment we were the two who could play Fischer. I was talking on behalf of two, so we discussed the things we should stress. Korchnoi asked me to talk because it was known that when he became emotional or nervous, he would say much more than he should. At that time we were friends. So I mentioned it to the delegates to the congress, but then when I beat Korchnoi, he gave an interview and changed his position completely. He said a completely different thing, so this was very unpleasant for me. The congress in Nice didn’t accept Fischer’s demands, and I must say that what he wanted was not realistic.

IF: So Fischer was making demands even before you became the challenger?

AK: Yes, then he continued to demand these conditions, so we had an extraordinary congress in ’75 after Nice. In this congress there was a big fight and in the end the delegates accepted one of Fischer’s conditions to play without limits to ten wins, which was crazy. Then Fischer sent them telegrams saying if they didn’t accept everything from his ultimatum, he wouldn’t play.

IF: At what point did you as the challenger know that you were not going to play Fischer?

AK: The first deadline was the first of April, so [Max] Euwe tried to contact Fischer for another two days, the second and third of April, and when he didn’t succeed on the fourth of April, he announced me as the new world champion.