Guyana has had a sad history of public accountability since it attained its Independence. A culture of “non-accountability” had developed at almost all levels of government so much so that by 1981 public accountability was brought to a standstill. While accountability was restored in 1992 and there is now annual financial reporting and audit of the public accounts, there is evidence of a marked decline, especially over the last ten years.

Today, we begin the first in a series of articles on Guyana’s system of public financial management since the end of the Burnham era in 1985. We will trace the efforts made during the two periods i.e. 1985-1992 and 1992-present date to address the issue of public accountability. We will then attempt to take stock of the progress we have made so far. Arising out of this review and analysis, we will propose an action plan for consideration by the new Administration that will emerge out of the 11 May 2015 elections.

Public financial management in the pre-1992 period

When the Hoyte Administration took over in 1985, the economy was in complete ruin; the country was technically bankrupt; and we were unable to service our external debts estimated at US$2.1 billion in 1992. Approximately US$1.5 billion of this amount was in relation to accumulated interest and penalties. While some efforts were made to address the issue of public accountability, priority had to be given to rebuilding of the economy, through various other measures. These included: (a) reducing the size of the public sector estimated at 80 per cent of the economy; (b) freeing up the economy to market forces as a replacement to a system of state control; and (c) entering into a Structural Adjustment Programme with the International Financial Institutions (IFIs). These austerity measures were necessary to arrest the decline and to turn the economy around. As a result, Guyana recorded seven years of sustained economic growth of on average 7.1 per cent during the period 1991 -1997, one of the fastest growth rates in the Caribbean region and among low income countries.

It was a remarkable achievement in such a short period of time, considering the untold damage done the economy during the Burnham era with the “critical support” from the then Opposition, now in power. It is therefore unfair for the Administration to remind us of what we had to endure in the pre-1992 period without: (a) admitting its own role in prodding the Burnham Administration towards a path of economic ruin through its failed experimentation with socialist concepts; and (b) acknowledging with some degree of appreciation the Hoyte Administration’s efforts to steer the economy back on course.

It was a remarkable achievement in such a short period of time, considering the untold damage done the economy during the Burnham era with the “critical support” from the then Opposition, now in power. It is therefore unfair for the Administration to remind us of what we had to endure in the pre-1992 period without: (a) admitting its own role in prodding the Burnham Administration towards a path of economic ruin through its failed experimentation with socialist concepts; and (b) acknowledging with some degree of appreciation the Hoyte Administration’s efforts to steer the economy back on course.

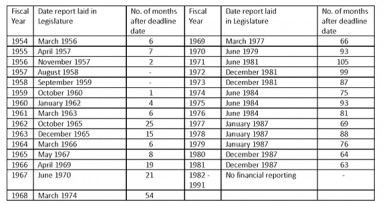

As at 1985, financial reporting and audit of the public accounts were eight years in arrears, as can be noted from the table below.

Trends in financial reporting and audit: 1954 – 1991

When we were a British colony, generally there was timely financial reporting and audit, except for the 1962-1963 period. However, the post-Independence period was characterized by a progressive deterioration, and it was evident that unless extreme measures were taken to reverse this trend, public accountability would be brought to a standstill, which was what happened.

In order to address the backlogged situation, the audits for the years 1977-1979 and 1980-1981 were undertaken together, and the related reports were tabled in the National Assembly in January 1987 and December 1987 respectively. This practice of auditing and reporting several years at the same time started in 1972, after a delay of nine years was experienced in producing the 1971 accounts. It is therefore not true to attribute the decay in public financial management to the Hoyte Administration. Rather, the reverse is true but his Administration was not afforded the luxury of time to have a complete sweep of the mess and decay that it inherited.

Public financial management in the post-1992 period

The current Administration reaped a windfall gain by pursuing the same economic policies inherited from the Hoyte Administration. It was, however, inevitable that at some point in time the foundation that was laid by the Economic Recovery Programme had to be re-evaluated and the necessary modifications introduced to sustain the momentum. Instead, we became preoccupied with the vigorous pursuit of negotiations with the IFIs with debt relief and write-offs, almost to the exclusion of programmes and activities would have ensured economic and social prosperity. It was therefore not surprising the economy plunged into a decline during the period 1998-2004 with an average growth rate of 0.6 per cent.

The Audit Office had almost single-handedly championed the cause of public accountability since 1990. It, however, took almost three years for its efforts to be realized. Based on a proposal for a two-pronged approach to be undertaken, public accountability was restored to some degree of respectability with effect from 1992. There is now annual financial reporting and audit of the public accounts. However, the Ministry of Finance’s attempts to put together the backlogged accounts were unsuccessful, and the effort had to be abandoned. The ten-year gap covering the period 1982-1991 would remain a significant blemish in our history of public accountability.

Politicians from both sides on the House sought to cast blame on the Audit Office for this gap. On the one hand, in its efforts to take credit for the restoration of public accountability, the present Administration accused the Audit Office of colluding with the previous Administration not to produce audited public accounts in an attempt to malign the main political Opposition, APNU. On the other hand, APNU felt that the Audit Office conspired with the present Administration not to have audited public accounts in order to put it (APNU/PNC) in bad light. Media reports of the early 1990s would confirm the falsehood in both assertions.

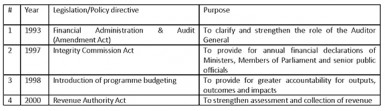

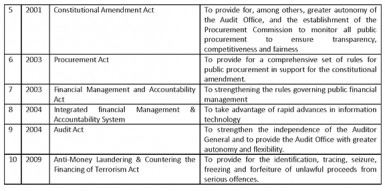

Reform initiatives in the post-1992 period

A number of reform initiatives in public financial management took place in the post-1992 period, mainly in relation to new legislation and policy directives, as shown below.

Laudable as they were, the implementation of these initiatives was a major issue. Most of them were not voluntary acts on our part. Rather, they were impositions by the IFIs as conditionalities for the rescheduling and write-offs of our external debts on the one hand, and for accessing new loans and grants. After all, no one would have been willing to grant us debt relief or other forms of financial assistance unless we demonstrated a serious commitment to improvement our public management systems and to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. However, experience has shown that accountability that is imposed is likely to result in minimum compliance. On the other hand, accountability freely and voluntarily given is so much enriched and long-lasting. This is especially so when we consider that being accountable is our moral duty and an act of ethical conduct.

Next week, we will review the above initiatives, and assess the extent to which they were implemented and their related impact.