Change in mindset

Last week’s article began a discussion on the economics of unity. The article set out what was at stake in the upcoming elections for the Guyana economy. As the Abilene Paradox reminds us, no one person or no one party could guarantee success without dissent and healthy debate. An effort would be made this week to define the economics of unity as it applies to Guyana and extend its application to the future prospects of the country. This effort is being made in the context of the goals that government is expected to achieve within the economy. As a reminder, the goals that government must achieve are security, liberty, equity and efficiency. For this writer and many others, the economics of unity is about minimizing tensions in the society, maximizing the value of the diversity of Guyana and providing equal opportunity to all Guyanese who are capable and willing to participate in the society. In other words, it is about tackling the factors that have kept this nation divided and that prevented it from moving forward. The effort, in parts, draws on post-emancipation history and sees the need for a change in the mindset that has plagued this country for a long time.

Minimizing tensions

Guyana is a multiracial society which was gripped by racial troubles before, particularly in the 1960s when there were open clashes between the two major races, Guyanese of African and Indian descent. Those unhappy events have led to lingering suspicions and phobia of each other. Some of these fears are being deliberately stoked by leaders of the incumbent party in an effort to bring suspicion and uncertainty to the fore in the upcoming elections in what appears to be an effort to turn the choice for government into a racial selection. While the tendency of many writers is to focus on the political discord of the 1950s, the modern day problem has its genesis in post-emancipation events that suppressed the economic opportunities of freed Afro-Guyanese.

In 10 days, Indo-Guyanese would celebrate their arrival in Guyana. Today, the event is a happy occasion, but it must have been traumatic for them to arrive in a strange land and to encounter unfamiliar faces during the indenture scheme. Little did they know that they too would become part of the exploitative game of the colonial planter who needed an adequate supply of labour on his sugar estate. In support of this viewpoint, reference is made to a citation of Walter Rodney’s finding by Da Costa in a 2007 Working Paper for the IMF. Therein Da Costa noted that Sandbach Parker, a colonial planter, reasoned that “so long as an estate has a large Coolie gang, Creoles must give way in prices asked or see the work done by indentured labourers”. Da Costa further observed in the paper that indentured workers arrived in Guyana “at a time when the supply of labour in Guyana appeared to be adequate, as evidenced by the groups of former slaves moving from estate to estate seeking work…”

In 10 days, Indo-Guyanese would celebrate their arrival in Guyana. Today, the event is a happy occasion, but it must have been traumatic for them to arrive in a strange land and to encounter unfamiliar faces during the indenture scheme. Little did they know that they too would become part of the exploitative game of the colonial planter who needed an adequate supply of labour on his sugar estate. In support of this viewpoint, reference is made to a citation of Walter Rodney’s finding by Da Costa in a 2007 Working Paper for the IMF. Therein Da Costa noted that Sandbach Parker, a colonial planter, reasoned that “so long as an estate has a large Coolie gang, Creoles must give way in prices asked or see the work done by indentured labourers”. Da Costa further observed in the paper that indentured workers arrived in Guyana “at a time when the supply of labour in Guyana appeared to be adequate, as evidenced by the groups of former slaves moving from estate to estate seeking work…”

No one could or should blame indentured workers for the way the colonial masters used them to undermine the economic progress of freed Afro-Guyanese. The arriving indentured workers could not have known the type of destabilizing impact their arrival in Guyana 177 years ago would have had on the economic situation of Afro-Guyanese who had just emerged from slavery. At the same time, one should not be annoyed with Afro-Guyanese for expressing frustration at the restraints placed on their economic progress even before they could get started on their journey of economic independence. Their purchase of land was rapidly being curtailed by colonial laws that were introduced in the 1850s that “prohibited the sale of land to groups of freed slaves and required the partition and taxation of land held by more than 10 persons”. Freed Afro-Guyanese saw their employment opportunities on the estates dwindle and the face in their place was an Indo-Guyanese.

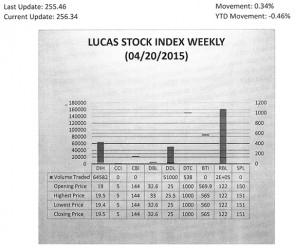

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) rose slightly by 0.34 percent in trading during the third period of April 2015. The stocks of four companies were traded with 278,142 shares changing hands. There was one Climber and no Tumblers. The stocks of Banks DIH (DIH) rose 2.63 percent on the sale of 64,582 shares. In the meanwhile, the stocks of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL), Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC) and Republic Bank Limited (RBL) remained unchanged on the sale of 51,000; 538; and 162,022 shares respectively.

Only the insensitive, knowing what challenges Afro-Guyanese faced each step after emancipation, would not see how and why Afro-Guyanese would be suspicious and even resentful of others who appeared to be obstructing their progress. There was no doubt that those in control of the country at the time wanted to keep wages of both indentured workers and freed Afro-Guyanese low and to prevent them from cooperating. Confronted by discriminatory labour practices and the unlikelihood of a long-term relationship with the sugar estates, Afro-Guyanese took the risk and moved away from their familiar surroundings and went into the towns and the “bush” to search for a living. Many became artisans while others found refuge in the bauxite industry after it began operations in 1916 in what is now Linden. Others went deeper to bleed balata and to search for gold. Those who could left the country.

It is not clear to this writer that Afro and Indo-Guyanese have stopped long enough to think about the economic effects they have had on each other. Even with the common identity of Guyanese, this writer also holds the view that Guyanese have not worked together consistently to bridge their differences and to achieve purposes common to all. The last 10 years of the PPP rule cannot escape such criticism. In assessing the performance of the PPP/C government over the last 10 years, one could argue that it has done the same things that the colonial masters did. Much of its public investment has been on infrastructural works with the construction being carried out by firms mainly from China that bring their own workers. In essence, the government has come up with no ideas better than those of 177 years ago in which foreign labour was used to suppress the wages and employment of local workers. In this instance again, all Guyanese workers are victims.

Further, Guyanese have seen a constant influx of Chinese investors and workers into Guyana over the past 10 years. This has happened at a time when there seems to be an adequate supply of workers as evidenced from the high unemployment rate among graduates from the University of Guyana and the large army of idle youths in the villages.

In addition, the PPP/C government adopted practices similar to those of colonial masters of using tax policy to help finance the importation of foreign workers into Guyana. This practice is leading also to the displacement of small and medium-scale Guyanese investors who find it difficult to compete with Chinese investors who enjoy greater economic and fiscal privileges than Guyanese. Important sectors of forestry, mining, telecommunications and the wholesale and distribution trade are under the control of Chinese investors too. If not stopped, soon the taxpayer funded Marriott will likely be sold at a deep discount to an investor of Chinese origin. In passing, it is interesting to note too that the government complains perennially about a labour shortage in the sugar industry but makes no effort to direct Chinese labour to the sugar estates. Again, this is being done without any effort to make the integration of the new Chinese arrival harmonious and smooth. The people of this country must have serious and open debates about the future labour, investment and commercial policies of the country. The economics of unity must not merely encourage that action. It must demand it if the country is to allocate and use its resources in a more efficient and less contentious manner.

Politicians and even academics have been in the habit of focusing on personalities and not the root cause of the problem of social and economic tension in Guyana. The government is continuing the discredited colonial practice of economic suppression and, as its current campaign shows, is clinging to racial incitement to make it sustainable. The use of crude, derogatory and contemptuous language sees current and ex-members of the disciplined services being openly maligned by persons whom they serve and protect. Divisive and unsubstantiated remarks that cast aspersions about the integrity of the military are not part of the economics of unity and should be condemned in the strongest terms. It is this sort of untruth and doubt that the economics of unity must confront and take Guyana off the treacherous track on which racial hatred, distrust and disrespect are being transported. It must make use of the laws against racial incitement and open discrimination against any religious, ethnic, gender or social groups with legitimate purposes. Remarks of the type being peddled by the incumbent government would not be necessary if it was interested in building a unified Guyana. Such positive upliftment is only possible through the economics of unity where government accepts, develops and faithfully carries out policies that seek to include all Guyanese in determining the direction and development of the country.

Maximizing diversity

A multiracial society contains people of diverse cultures and background. Ultimately, it is the condition of the nation state that matters and that is a result of how the cultures interact and fuse with each other. The economic history of Guyana as explained by some historians and economists reveals that the socialization process of Afro and Indo-Guyanese was not easy. The experience of countries like Belgium, Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Turkey for example, with longer histories than that of Guyana, confirms that the process is complex and can contain many hazards and setbacks like the tracks to the several peaks of the Himalayas. Historians point out that language was a major problem in the case of Guyana, and so were culture and religion. The language barrier made communication difficult and the exclusive nature of the culture and the Hindu religion made the acculturation process near impossible.

But Guyana’s diversity can be its strength and it must be used that way. Beyond the personal, Guyana’s diversity should allow it to be much more creative and form new knowledge from the separate sets of culture, information, skills and experience that could emerge from a united effort. The exposure to new ideas and experiences can strengthen the intellectual capacity of the country and expand the understanding of each other and the geographic space in which Guyanese must dwell. The biased allocation of resources such as the radio and TV licences are unhelpful to any process that seeks to maximize diversity.

(To be continued)