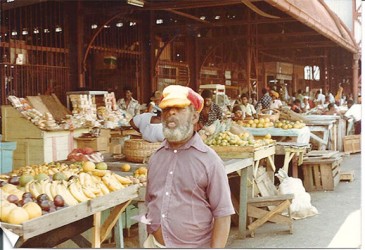

The vending row begins on Water Street just outside Bounty Supermarket, pushes west on the pavement towards Stabroek Market then forks sharply in the direction of Demico House. The other fork continues on its southward path, extending towards the furthest extreme of the market. It is, almost certainly, the most congested single trading space in the city, populated overwhelmingly by female vendors offering vegetables, fruit, groceries and assorted items from makeshift stalls packed tightly together.

Some of the vendors are veterans of the streets who have survived what they say were the “bad old days” when the City Constabulary swooped down on pavement vendors with monotonous regularity, seized and impounded their goods and made them pay to retrieve them. These days, the vendors say, the relationship with the Constabulary is one of greater “understanding.” It is a matter, one vendore told Stabroek Business, of “living along.” At nights, the presence nearby of the City Constabulary as well as a Guyana Police Force outpost provides a measure of peace of mind.

There may well be at least 100 vendors trading in what is a highly populated and favoured locale. In the evenings, particularly, people making their way to the bus park to travel to any location in or out of the city find themselves close to this extended outdoor arcade. Not surprisingly, trading is brisk in the evenings.

Some of the women vendors with whom Stabroek Business spoke live in villages west of the Demerara River. They cross the river by way of the Demerara Harbour Bridge early in the mornings and late at nights. Some bring their goods with them. Others have their greens and vegetables sent across the river by boat.

Some of the women selling fruit in the area closest to Demico House are from villages on the East Coast Demerara. Carol has been vending in the same spot for more than five years. Business, she says, is usually “up and down.” Other vendors appear comfortable in what is a far from convivial circumstance. Some of them bring infants and small children with them and using an assortment of cardboard and sponge to create makeshift beds. It is clearly a demanding routine.

Some of the women vendors come from farming families. Perhaps not surprisingly, their spouses and children work on the farms whilst they take care of what Rhoni calls “the business side of things.” She believes that women are usually better at doing business though she concedes that in her particular case it is her husband’s fondness for more than the occasional drink that has caused her to take on the vending.

The stall next to Rhoni’s was being tended by a stern-faced mixed-race woman who declined to say her name. She did say, however, that she lived “across the river” and that she had come from a farming family. She seemed entirely focused on selling an enormous pile of impressive-looking tomatoes. At $90 a pound there was simply no competition close to her and she was plying her trade with a certain casualness, not particularly bothered that a few shoppers were simply stopping to have a look and moving one. She seemed to feel sure that at least some of them, having discovered that there was no better bargain to be had, would return. She appeared rather less mindful of getting rid of a sizeable basket of celery, mostly not bothering to answer when enquiries were made about the price.

The end of the regular working day had come and gone and people were beginning to find their way to the open-air ‘arcade.’ The human and vehicular traffic was beginning to create a somewhat dangerous congestion. No one seemed to mind, however. Apart from the stern-faced woman with the good-looking tomatoes the vendors were offering pumpkin, squash, bora and celery. Judging from the enthusiasm with which people were shopping it appeared that the prices were good.

The first woman selling bananas on the fork that headed towards Demico House appeared to have given up on doing business for the day. In the light of the setting sun it was obvious that the day’s sun had taken full toll on her fruit stall. She had already ‘written off’ a heap of avocadoes and cherries, pushing them to one side of the stall, a sign that she was no longer under any illusions that they were saleable. Her energies were barely focused on selling off the bananas that remained. There was a sign lying on the stall marked 2 pounds for $100, though it was evident that the information no longer applied to the woebegone-looking fruit nearby and that she would simply accept the first reasonable offer for them. A man with a little boy stopped at the stall and after a brief and less than intense period of negotiation took the entire lot of bananas – probably about ten pounds – for two hundred dollars. He said he was buying the fruit for his parrots.

Once she had disposed of the bananas Blossom dipped two fingers laden down with rings into the pockets of a huge apron tied around her waist to remove huge quantities of grubby looking banknotes. She sat down and began to order them. Simultaneously, she spoke with Stabroek Business about her life as a vendor. She had worked as domestic, but had left the job after the husband of the woman who had employed her had demanded that they have a sexual relationship. Afterwards she had bought and sold fish but the earnings were not sufficient to keep herself and her son. Buying and selling fruit meant that she had to travel from her home at West Coast Berbice to the city every day. But there was more money to be made in selling fruit.

Darkness hides the unseemly piles of garbage sitting on the pavement and in the gutter close to where the vendors ply their trade. There is, clearly, a disconnect with the environment in which they ply their trade. The relationship between them and the municipal authorities as far as garbage disposal is concerned is unclear.

One of the more interesting features of downtown street trading is the relationship between the traders and the drug addicts. The latter function as general helpers, running errands and moving ‘loads’ from one place to the next. They appear to work for particular groups of vendors though what they get paid is unclear. One woman told us that some of them would work for food or for the price of a ‘smoke.’ Whatever the arrangements they are not entirely trusted by the vendors.

Southward, towards the furthest extreme of Stabroek Market the pattern of vending changes. A smaller number of vendors offer groceries: bread, milk, butter, onions, potatoes and canned items. Most of them are not disposed to talking. Vern says that if you get distracted customers could pass you by. Apart from her mini supermarket on the stretch of road outside the market she runs a similar service in a small area in the yard where she lives. Her prices are marginally higher than those in the supermarkets but her opening hours justify higher prices. She has been throwing weekly box for about seven years. That helps her to keep her grocery shops stocked. Asked about the prospects of starting an established grocery of her own she laughs. It was a laugh that said that – for the time being at least – such ambitions were the last thing on her mind.