As the Minister of Public Health Dr. George Norton completes his fact-finding walkabout, sooner or later he will have to put to us some holistic organisational solutions to the problems in the health sector as he envisages them. Therefore, before concluding, as promised last week; with some extrapolations, let me make a trite point that is usually neglected in the firmament of political competition.

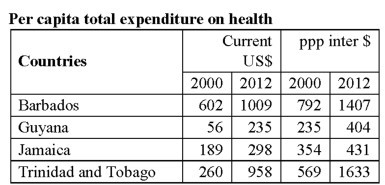

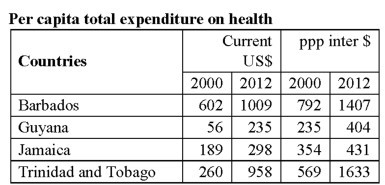

As with the other social services, health outcomes are very much related to the level of economic resources available to the sector. But as the figures below indicate, there is also deep interconnectedness with other factors, e.g. culture, general poverty, geography and the level of education.

World health statistics 2015, WHO

International $ = one US dollar

* Life expectancy at birth

** Probability of dying by age 1 per 1000 birth

***Per 100,000 birth

Although the situation has improved significantly since 2000, in terms of the actual number of dollars going to the health sector, Guyana still has less than other major Caricom countries. This has more to do with the fact that Guyana is poorer than those countries than with the parsimony of the government. At 6.6% of GDP in 2012, Guyana was spending a larger proportion of its income on the health sector (Ibid).

À propos the deep interplay suggested above, one would have expected that the significant progress made in poverty reduction over the years would have impacted life expectancy more positively, but if the above figures are correct, it has hardly improved since 1990.

As is pretty well known, notwithstanding the hype about Guyana becoming a health leader in the Caribbean, on most indicators Guyana lags far behind the other countries. For example, a pregnant woman in Guyana is more than four times more likely to die in childbirth than her counterpart in Barbados. And even if she succeeds in giving birth, her child is twice as likely to die before reaching her/his first birthday.

But again, the vast disparities of outcomes (e.g. infant and maternal mortality in Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago) when related to available resources, speak to a more varied connection and most importantly suggest that with a different focus much more might be achieved with far less.

These observations should help the minister to understand that he would do both the country and himself a great disservice if, under the usual political pressure to deliver, he ignores this vital (even if multidimensional) relationship and sets himself all kinds of unrealistic objectives.

I concluded last week that although legislative, personnel and other institutional changes are important, the real value of creating autonomous management bodies is derived from our being able to properly set and monitor targets that encourage improvements in service delivery. Management must be presented with clearly achievable goals against which it can be held accountable.

Of course this kind of arrangement runs somewhat counter to the commonplace notion that management requires as detailed as possible oversight of the managers’ obligations. Furthermore, we live in a political context in which day-to-day intervention routinely results from the demands of some of the very people who persistently complain about micromanagement and political patronage. How can one justifiably hold a manager accountable if the minister consistently intervenes and directs the day-to-day operations of the organisation?

An important early decision one has to make, therefore, is whether the extant system, including the expectations of functional superiors, is consistent with this type of management arrangement. Sometimes it is not and in those circumstances it may be better to look at other ways of managing the sector. Indeed, the earlier efforts at reforms at the Georgetown Public Hospital provide a good example of a variant of this very point.

As we have seen, the health system proper (and hospitals in particular) is not responsible, e.g., for all the maternal deaths that take place. To create proper achievable indicators one would have to assess the level of deaths that are the result of hospital interventions and create goals that the hospital administration can be expected to fulfill in a given time frame.

In a large established institution such as the Georgetown Public Hospital, after properly benchmarking the level of the present services, hundreds of indicators and sub-indicators will have to be created and effectively monitored by both the administration and periodically by the subject ministry. This raises the question of the scheduling of the reforms: at what rate and in which areas are the reforms to be initiated.

Partly to help to benchmark the services the hospital was providing but also to try to institutionalise public transparency as another level of pressure on the hospital management to perform, in 2000 the ministry completed the first – and I believe last – public hospital inspection under the chairmanship of Dr. Vibart Shury.

The Shury inspections sought to be comprehensive, touching upon some seventy services. In many ways the report was quite scathing, the media picked up on it and elements in the political establishment, rather than seeing it as something that should be periodically done to help improve care delivery, thought that it played too much to opposition propaganda. The inspection of private hospitals is institutionalised in the ministry but the public hospital was thought immune from such inspections even though a semi-independent board was being put in place!

As a matter of principle, whether or not one continues with establishing autonomous authorities in the health system, the minister, as part of his drive to improve transparency and delivery, should institutionalise regular neutral inspection and reporting on the conditions at all public hospitals. Then he will not have to wait until he makes his rounds to have some better understanding of the real conditions on the ground.

In my opinion, the health sector requires major reforms and the minister should eschew short term fixes and the pressure towards micromanagement. He should seek to put in place arrangements that will allow management to be creative and to set and monitor targets based upon performance incentives and sanctions. In itself, whatever system he chooses, this would be a formidable enterprise that will only become embedded if followed persistently over many years.