A 2010 McKinsey follow-up study, ‘How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better’ made the obvious but yet noteworthy point that improvements in the education system are possible from any level of development. It also concluded that, ‘The school systems examined in this report show that the improvement journey can never be over. … systems must keep expending energy in order to continue to move forward: without doing so, the system can fall back, and thereby threaten our children’s well-being.’

Every country in the world is focused on education reform but the process of reform needs to be properly understood. England reformed the funding of schools; school governance; curriculum standards; assessment and testing; the inspection of quality; the roles of local and national governments; the range and nature of national agencies; the relationship of schools to communities; school admissions, etc. ‘Yet a report published by the National Foundation for Education Research in 1996 demonstrated that between 1948 and 1996, despite 50 years of reform, there had been no measurable improvement in standards of literacy and numeracy in English primary schools’ (How the world’s best performing school system come out on top. McKinsey Co., 2007).

Every country in the world is focused on education reform but the process of reform needs to be properly understood. England reformed the funding of schools; school governance; curriculum standards; assessment and testing; the inspection of quality; the roles of local and national governments; the range and nature of national agencies; the relationship of schools to communities; school admissions, etc. ‘Yet a report published by the National Foundation for Education Research in 1996 demonstrated that between 1948 and 1996, despite 50 years of reform, there had been no measurable improvement in standards of literacy and numeracy in English primary schools’ (How the world’s best performing school system come out on top. McKinsey Co., 2007).

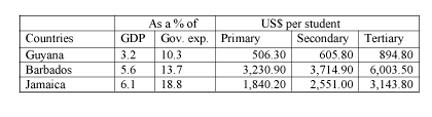

In Guyana too, every strategic plan that has been consistently delivered since about 1990, together with the many reputable international interventions, have attempted to incorporate new knowledge into the education system. But whether or not