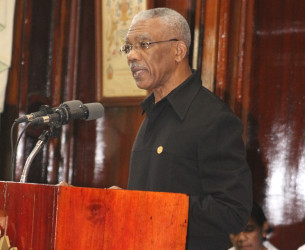

President David Granger yesterday continued the pressure on Venezuela over its stunning bid to appropriate Guyana’s Atlantic waters, declaring that a replacement decree issued by Caracas was still exceptionable and that Georgetown would broaden its diplomatic offensive to counter it.

Addressing the National Assembly for the second time in less than a month, Granger declared that the May 26th decree which sparked a crisis in relations with Venezuela was “like a fishbone in our throats”.

The Head of State and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces reiterated that the short-term objective was to have all threats withdrawn by Caracas while in the longer term Guyana would be pursuing a permanent juridical settlement.

Granger said that while the new Decree No. 1.859 of July 6th does not contain the coordinates of Decree No. 1.787, it does include a general description of all the defence zones, with the attributes of Eastern, Central, and Western regions, cohering with previous versions of the Decree.

“It goes further to state that these ‘defence zones’ are spaces created to plan and execute integral defence operations. This portion remains offensive to Guyana since there continues to be a threat of the use of force in these areas.

“The Co-operative Republic of Guyana therefore rejects the description of its maritime territory as a ‘defence zone’ of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela”, Granger declared to the assembly which comprised only APNU+AFC members as the PPP/C continues its boycott.

Caracas issued the July 6th decree in the wake of vocal criticism of the May 26th decree from Guyana, Colombia and Suriname. In addition, Guyana was able to mobilise solid support from the Commonwealth and over the last weekend, CARICOM called on Venezuela to withdraw the elements of the decree that were offensive to its member states.

The May 26th decree took aim at waters off Guyana’s Demerara coast which had hitherto not been targeted by Venezuela and was therefore immediately considered as an expansion of a territorial claim in violation of the 1966 Geneva Agreement which sets out the basis for finding a solution to the border controversy between the two countries. Importan-tly, just days before the decree, ExxonMobil had announced that it had found what appeared to be a significant oil deposit in the waters off Demerara.

Saying that he wanted to bring the National Assembly up to date with the two decrees issued by Venezuela and which have infringed on the exercise of the country’s sovereignty and rights to its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), Granger pointed to Venezuelan Presid-ent Nicolás Maduro announcement on July 6th that he had replaced the decree of May 26th.

Granger quoted Maduro as saying “”I have decided to take all the content of this decree 1787 to the State Council and the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ) and, in the meantime, taking the doctrinarian, constitutional criteria (…) issue a new decree to supersede it (the decree issued on May 27) in all its parts.”

Granger charged that Decree No. 1.787 sought to create the “Atlantic coast of Venezuela.”

“This geographical fiction purports to justify the extension of that country’s sovereignty over Guyana’s territorial waters in the Atlantic Ocean off the territory of five regions of the Essequibo and over a distance of 200 nautical miles range thereby completely blocking Guyana’s access to its own exclusive economic zone. The Decree also created so-called “Areas of Integral Defense of Marine Zones and Islands,” extending sovereignty even into part of Suriname’s maritime space”, Granger contended.

He said this was a flagrant violation of the Geneva Agreement and that the Venezuelan government therefore had no grounds under the Geneva Agreement or international law to oppose the work by ExxonMobil in the `Stabroek Block’ off the Demerara Coast.

Stating that Guyana has never used aggression against any state, Granger asserted that Georgetown would however not tolerate a threat to its territorial integrity and reiterated his position to the CARICOM Heads that decree 1.787 was an act of aggression against Guyana.

He pointed out that at the CARICOM meeting in Barbados, he met with UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and conveyed to him Guyana’s position on the decree. He noted that the Secretary General has committed to sending a mission to both countries and that Guyana would happily receive it.

Granger traced decades of Venezuela’s attempts to interfere with economic projects because of the border controversy and adverted to the 2013 incident where a Venezuelan Navy vessel detained a vessel conducting studies for US oil explorer Anadarko.

He said: “The expulsion of an unarmed, seismic survey vessel from Guyana’s exclusive economic zone by a Venezuelan naval corvette, therefore, was a dangerous and egregious exhibition of gunboat diplomacy. The corvette — PC 23 Yekuana — of the Bolivarian Navy of Venezuela entered Guyana’s exclusive economic zone around 16:00 h on Thursday 10th October 2013 and, under the threat of force, prevented the unarmed vessel — Teknik Perdana — from conducting seismic surveys. The Yekuana incident was (an) extreme use of armed force. It violated the Charter of the United Nations. It threatened regional peace and security. It contradicted the promise of President Nicolas Maduro Moros who, speaking at a public event in Nueva Esparta shortly after his visit to Georgetown in August 2013, solemnly promised:

`Any issues we have with our neighborly countries, either serious or not, will be solved peacefully through the diplomatic channels and international law. There will never be war. We have declared South America the land of peaceful people…’”

Granger described the efforts taken by a number of Venezuelan presidents since 1968 to economically undermine Guyana because of the border controversy.

* President Raúl Leoni Otero placed an advertisement in the Times newspaper of London on 15th June 1968 to the effect that the Essequibo belonged to Venezuela and that it would not recognize economic concessions granted there by the Guyana Government. He then issued Decreto No. 1.152 of 9th July 1968, purporting to annex a nine-mile wide belt of sea-space along Guyana’s entire Essequibo coast and requiring various agencies, including the Defence Ministry, to impose Venezuelan sovereignty over it.

* President Rafael Antonio Caldera Rodriguez blocked Guyana’s attempt to allow petroleum exploration rights in the Essequibo by DEMITEX, a German company.

* President Luis Herrera Campins reinforced the blockade by obstructing the development of the Upper Mazaruni Hydro-power Project. He issued a communiqué in April 1981 stating that, because of “Venezuela’s claim on the Essequibo territory,” it “asserted the rejection of Venezuela to the hydro-electric project of the upper Mazaruni.” Venezuela’s Foreign Minister, José Alberto Zambrano Velasco, wrote a letter giving the President of the World Bank an ultimatum to refrain from financing the Upper Mazaruni Hydro-Electric Project.

* President Carlos Andrés Pérez paid a visit to Guyana in 1978 during which he indicated Venezuela’s willingness to help finance the hydro-electric power project in the Cuyuni-Mazaruni Region of the Essequibo. Behind the apparent friendliness, however, the realpolitik of Venezuela’s geo-political interests remained unchanged. Perez frankly expressed Venezuela’s geopolitical interest in gaining a Salida al Atlantico – access to the Atlantic – from the Orinoco delta by offering to reduce the territorial claim to about 31,000 km2 in return for the Essequibo coast.

* President Jaime Ramón Lusinchi reaffirmed the claim of previous Presidents insisting that it could not be renounced.

* President Hugo Rafael Chávez Frias issued a July 2000 declaration to prevent the Beal Aerospace Corporation from establishing a satellite station in the Barima-Waini Region and opposed the issuance of petroleum exploration licences to American companies off the Essequibo coast.

* President NicolásMaduro Moros by issuing Decree No. 1.787 and Decree No. 1.859 in 2015 has continued the attitude of his predecessors.

Granger adumbrated a series of measures which Guyana took to counteract Venezuelan hostility including the Maritime Boundaries Act and the Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act, 1986. He said the enacting of legislation and the issuing of regulations meant that sovereignty and jurisdiction were openly and continuously exercised over these maritime areas by Guyana.

Defiantly, he said Guyana will continue furthering a wide range of diplomatic options as its first line of defence.

“Guyana will continue to pursue a wide range of diplomatic options as its first line of defence. Guyana remains resolute in defending itself against all forms of aggression. We remain wedded to the ideal of peace. We have never, as an independent state, provoked or used aggression against any other nation. We have never used our political clout to veto development projects in another country. We have never discouraged investors willing to invest in another country. We have never stymied development of another nation state. We do not expect, not will we condone, any country attempting to do the same to us”, Granger said.

Noting the sizes of the two countries, Granger said:

“Guyana has no interest or intention to be aggressive towards Venezuela, a country of 912,050 km2, more than four times the size of Guyana; a country with a population of more than forty times that of Guyana; a country with armed forces — the National Bolivarian Armed Forces — FANB – with more than twenty times as many members as Guyana’s Defence Force. How can Guyana launch an aggression against Venezuela?”

He asserted that he fully expects Venezuela to observe the 1897 Treaty, the 1899 arbitral award and the 1905 demarcation of the of the boundary between Guyana and Venezuela pursuant to the arbitral award.

In his address to the Venezuelan legislature on July 6th , Maduro announced the recall of Caracas’ envoy here for consultations and a review of relations with Guyana.