By Tony Cozier

The topsy-turvy cricketing life of Denesh Ramdin has taken another back flip.

Given the history, it is premature to believe that his reliably reported omission from the West Indies team to the triangular ODI series in Zimbabwe next month is his last tumble.

Over the 15 years since he first played in West Indies colours in the champion team in the one-off under-15 international Costcutter Cup in England in 2000, Ramdin has experienced the idiosyncracies of West Indies administrators and selectors more than most others. Every time he has surmounted them.

Only Jeffrey Dujon of West Indies’ wicket-keepers has played more Tests, 79 to Ramdin’s 69; only Dujon (167) and Ridley Jacobs (147) have more than his 127 ODIs. Neither was ever dropped.

Only Jeffrey Dujon of West Indies’ wicket-keepers has played more Tests, 79 to Ramdin’s 69; only Dujon (167) and Ridley Jacobs (147) have more than his 127 ODIs. Neither was ever dropped.

Ramdin had seemingly made the position his own with impressive performances in both departments following his Test debut in a strike-weakened team in Sri Lanka in 2005; even after amassing 166, his first Test hundred, in a high-scoring match against England in Barbados in 2009, a couple of inadequate series subsequently in Australia and the Caribbean against South Africa prompted the selectors to turn to the diminutive Jamaican Carlton Baugh.

The unkindest rejection was the choice of the unproven young Antiguan, Devon Thomas, for the 2011 World Cup after Baugh’s withdrawal through injury.

Ramdin spent 16 Tests and almost two years biding his time. He regained his place for the series in England in the summer of 2012; in his first 12 Tests back, he had hundreds against England at Edgbaston, Bangladesh at Mirpur and New Zealand at Hamilton and averaged 53.61. More recently, there were two rapid hundreds in ODIs against England and Bangladesh at home. It was a turnaround that brought him the Test captaincy in June 2014 after Darren Sammy was replaced following calamitous series in India and New Zealand.

For all Ramdin’s experience, it was a curious choice for he had become embroiled in uncharacteristic controversy since his return to the team.

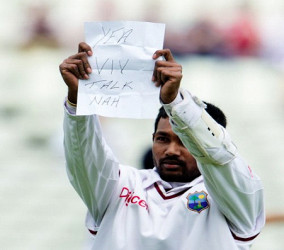

When, with the aid of last man Tino Best’s cavalier 95, he completed his hundred at Egbaston, he turned in the direction of the pavilion and produced a piece of paper from his trousers’ pocket.

“Yea Viv, talk nah” it read. It was a reproach to Sir Viv Richards who had previously questioned his contributions in the earlier matches. The ICC immediately fined him 20 per cent of his match fee for “conduct unbecoming”. Ramdin later apologised but it remains a prominent negative mark on his c.v..

Nor was it to be the only one. He copped an ICC two-match suspension during the Champions Trophy in England the following year for allegedly scooping the ball from the turf and claiming a catch in the match against India at the Oval. For all that, he was generally accepted in the West Indies as the only logical option. If his cautious tactics and losses to New Zealand and Australia in his 11 Tests at the helm have attracted adverse comments, they were counter-balanced by the clean 3-0 sweep over Bangladesh and a plucky 1-1 draw against England.

All were in the Caribbean; the greater challenge will be in Sri Lanka and Australia at the end of the year. His love-hate relationship with his own Trinidad and Tobago Cricket Board (TCCB) could determine whether he keeps the job.

After Ramdin’s highest score by a West Indian in a home ODI (169, including 11 sixes) against Bangladesh in St.Kitts last August, the TTCB was effusive in its praise. It was, it gushed in a media release, “a tribute to the hard work and commitment that he has been able to produce the kind of form this season and to show the unique talent and promise we at the TCCB had recognised many years ago”.

The mood markedly changed two months later after Ramdin returned from India with the team that prematurely abandoned the tour over a contracts dispute with the West Indies Cricket Board (WICB). Ramdin claimed that he had been restricted from participating in a practice session with the Trinidad and Tobago team; he felt “hurt and embarrassed”.

He said when he later met with the TTCB he was told that he “did not demonstrate proper leadership in relation to the tour of India”.

It advised him that he would be replaced as team captain by all-rounder Reyad Emrit for the inaugural WICB Professional Cricket League.

Ramdin saw this as punishment for being among the players who aborted the Indian tour “contrary to the undertaking given by the WICB” that there would be no discrimination or victimisation.

It was a widely held view that Dwayne Bravo’s forthright comments during the standoff with the WICB led directly to his removal as ODI captain. In spite of the WICB’s denials, Bravo clearly paid the price, as Ramdin did for Trinidad and Tobago. That Ramdin was retained as Test captain for the series against England and Australia was a paradox typical of the WICB. He might find the appointment of 23-year-old Jason Holder as the new ODI skipper instructive.

At that age he promised to develop into the long-term captain. He was captain of the under-19s in the ICC Youth World Cup in Bangladesh in 2004, leading them to the final against eventual champions Pakistan. He marked his Test debut in Sri Lanka in 2005 with a half-century, impressive his glovework and a composed attitude. A worthy replacement, in appeared, had been found for the long-serving Ridley Jacobs. His performances until his first slump in form put him on the sidelines five years later confirmed the optimism. On their first tour of Australia at the end of 2005, he and Dwayne Bravo saved some face in a 3-0 drubbing in the Tests with a seventh wicket partnership of 182 in the second in Hobart. Bravo’ 113 was in his eighth Test, Ramdin’s 71 in his fourth.

“Our goal is to play for 14 or 15 years so as to ensure that, when Brian (Lara), Shiv (Chanderpaul) and the senior guys move on, we can turn things around,” Bravo said at the time.

Future upheavals render that quote now sadly laughable.