Critics of the popular play in contemporary drama, and very specifically those in the Caribbean and Guyana, often hold it up against what is called ‘serious’ theatre. The popular play is held to be inferior to the more serious genres of greater substance, form and subject, including drama of the ‘classical’ type, or even the classical plays themselves, which were the models of western drama. But repeatedly, close analyses tend to reveal not only the growing influence of the popular play on the more serious forms, but the deep, substantial, ancient roots of much of the popular theatre, and even the common roots of both the popular and the serious.

To go further, one will find popular intentions and focus in the best of classical drama, the best of theatre generally, and the consistently dominant influence of the audience throughout history. All theatre is a relationship between the audience and the performance, and this has perennially influenced form.

It is easy to do a study of the popular elements, the attempts of audience appeal, and the strong audience factor in what are looked upon as the best models in western theatre. It is not difficult to find commonality in the roots and development of both the popular and the prestigious models. This includes the behaviour of the audience and the attempts by playwrights to appeal to and respond to that behaviour. A very good example is the rise of farce and slapstick in the morality plays of the mediaeval era, and how these evolved into their refined handling in the Elizabethan era including Shakespeare. Similar roots, evolution and influence make very interesting study in the Caribbean.

It is easy to do a study of the popular elements, the attempts of audience appeal, and the strong audience factor in what are looked upon as the best models in western theatre. It is not difficult to find commonality in the roots and development of both the popular and the prestigious models. This includes the behaviour of the audience and the attempts by playwrights to appeal to and respond to that behaviour. A very good example is the rise of farce and slapstick in the morality plays of the mediaeval era, and how these evolved into their refined handling in the Elizabethan era including Shakespeare. Similar roots, evolution and influence make very interesting study in the Caribbean.

However, the focus here is on one type of classical drama and its powerful influence. It shows some of the common roots, the similar persuasions and the importance of the audience in both what is considered popular and what is considered the best of drama. It also shows the serious influences of the former on the latter.

That form of theatre in focus here is the Senecan drama, which may also be referred to as the Revenge Tragedy, the Revenge Play and the Senecan Revenge Tragedy. It belongs to the line of drama considered the best in western eyes, that is, classical theatre. Moreover, it was a source of much that was developed, and much that was copied in the Elizabethan theatre of the sixteenth century and after. It served as a model for and became an influence of some of the best plays of all time.

None of the sources consulted describe the revenge tragedy as a popular play. Much is made of its moralistic concerns and function. The accounts dwell on its treatment of the serious subject of vengeance and the way Senecan drama handles the thin line between revenge and justice. They interpret the plays as pointing to the errors of private vengeance and even punishing the hero of the plays for avenging murder with murder. Elizabethan prose writer Francis Bacon comments on this in his treatment of revenge, which he says brings the avenger down to the level of the murderer, and that it is superior and “princely” to forgive. The accounts show the handling of the Senecan models by sixteenth century playwrights as meritorious use of form in drama. And the critics of the popular play in the Caribbean revere the Elizabethan plays as serious classics in theatre.

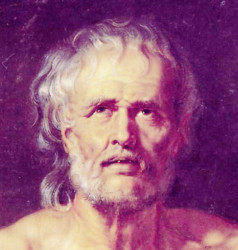

The Revenge Tragedy and the Revenge Play were named after the man regarded as its founder – the Roman playwright Seneca (circa 4 BC – 65 AD). Scholar and biographer Miriam Griffin cautions about accepting some of the ‘facts’ about Seneca, claiming that some of it might be from the “imagination” of writers confronting a paucity of evidence. However, Lucius Annaeus Seneca, is also described as a stoic philosopher and a politician – advisor to Roman Emperor Nero. He wrote 9 or 10 plays which survived (sources differ on whether 9 or 10, with one or two where authorship was disputed). He became quite wealthy and influential in his lifetime.

The plays developed a kind of formula which gave rise to the revenge tragedy and were extremely popular in the Elizabethan period and after, following their rediscovery in the sixteenth century. In the formula, the plot surrounds the quest for revenge by the hero following a wrong committed against him or the murder of a relative or someone close. Ghosts appear in the plays often acting as agent provocateurs urging the hero to achieve vengeance. In some plays there is actually a character named ‘Revenge’ who performs this function. Seneca’s revenge plays are exceedingly bloodthirsty, often the pursuit of vengeance becomes complicated and fraught with errors. There are killings, murders, carnage and mayhem, with the stage strewn with several corpses at the end.

Seneca’s plays were influenced by the Greek drama as well as Roman poetry and theatre that emerged after the heights of Greek theatre in Athens, 5th – 4th Century BC. It must be pointed out that in the Greek plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, the tragedians who influenced Seneca, no violence is actually shown on stage. Any killings and bloodshed are not seen by the audience – they take place off-stage and only the results are exposed on stage afterwards. But in Rome the violence is quite a part of stage business.

It goes further that this was a major contributor to the popularity of the plays. The audience liked the carnage as they did the various intrigues surrounding the pursuit of vengeance. These were major features which made this type of play popular in the late 16th Century. By that time, the slapstick of the late Middle Ages had continued and was drawn on in serious plays by some of the best dramatists including Christopher Marlowe (in Doctor Faustus, for instance).

The best and most obvious Elizabethan play to draw directly on the Senecan formula is The Spanish Tragedy (circa 1587) by Thomas Kyd. It was also exceedingly popular with several performances and re-stagings over many years. Although the play begins with an end to the war between Spain and Portugal, it continues with a recurring cycle of murders, killings, hangings, violent attacks, suicides, betrayals, treachery and deceit. The play’s revenge motif is driven by two ghosts – the character Revenge and the ghost of Andrea, who pushes for his own killing to be avenged. Two main characters, the heroine Bel-Imperia and Don Hieronimo are aggrieved parties who decide to seek vengeance since they were being denied justice. The plot is full of deceptions, notoriously led by Lorenzo against his own sister, Bel-Imperia. It uses the technique of the play-within-a-play and the many complications all leading to more bloodshed.

The Spanish Tragedy was a very popular play in its time, which testifies to the audience demand. More than most other revenge plays, it follows Seneca closely and even acknowledges the debt within the text of the play. Yet critical accounts treat it as a serious examination of vengeance versus justice and the cult of vengeance associated with the Spanish Court. But it is a play with obvious roots in a popular genre, made superior by skilled treatment in the hands of Kyd.

Not only the popular elements of Seneca, but the very play The Spanish Tragedy, inspired the best of them all, William Shakespeare. The Bard of Avon, who unashamedly made use of the popular audience appeals of mediaeval extraction in many plays, did it again in some of the most accomplished and acclaimed tragedies. These include the tragedy of Hamlet, the one most directly influenced by The Spanish Tragedy. The ghost of King Hamlet appears in the role of Revenge, while the Prince, his son, embarks on the quest for vengeance for the murder of his father. Like Bel-Imperia and Hieronimo, Prince Hamlet uses the play-within-a-play to catch his villain, encounters multiple complications and ends with the usual multitude of slain persons strewn about the stage.

Yet Hamlet is one of the world’s great tragedies, by no means ever mentioned as a popular play. Of course, it deals with several weighty issues and the supposed reluctance of the prince to kill his father’s murderer is one of them. His many moral principles get in the way of cold-blooded murder, even if it would be justice. Doing the right thing weighed heavily on Hamlet’s mind and feed the worthy themes of the play. Yet Hamlet proves himself over and over in the drama to be cold-blooded when he is so moved, quick to action, violent and murderous. He satisfies the Elizabethan (and the Roman) thirst for blood and hot action. These come in the way he treats both his girlfriend and his mother, his ruthless killing of Polonius, his calculated design to send Claudius straight to the cauldrons of hell, his vicious attacks against the savage pirates at sea, and his cool, cold-blooded sending of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to their deaths in England.

Shakespeare was at it again in the Roman tragedy of Julius Caesar. Mark Antony invokes Até, the goddess of spite, fury and vengeance as well as the demons from hell when he calls for revenge to get justice for the assassination of Caesar. “Woe to the hands that shed this costly blood,” he swears. “That this fell deed shall smell above the earth,/With carrion men groaning for burial.” He sounds the Senecan battle cry: “And Caesar’s spirit ranging for revenge/With Até by his side come hot from hell/And in these confines in a monarch’s voice/Cry ‘Havoc!’ and let slip the dogs of war.” Caesar’s ghost was equal to the challenge and appears in the guise of the character Revenge to the two architects of his murder when he tells them, “I shall see thee at Philippi.” Then after their defeat at the battle of Philippi, both Cassius and Brutus acknowledge the successful achievement of vengeance and justice with the separate words, “Caesar, thou art avenged, even with the/Sword that killed thee,” and “Caesar’s spirit now be still, I killed not/Thee with half so good a will.”

The most bloody revenge drama of them all has to be Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus. It is a chilling, blood-curdling play with scene after scene of spite, adultery, betrayals, murder, rape, mutilation and revenge slaughter. It has as much of these elements as a popular audience could demand. There are intrigues, roguery, deceptions and vindictiveness. The queen has a child for her secret lover, Aaron, a black man who is as vicious in his own defence as he is in vengeance. The child, who is, of course, half black, could not be revealed to the Court, but Aaron hatches a scheme to save his offspring and the honour of the queen by substituting the child with another white baby born at the same time.

Yet later in the play this same child is slaughtered as an act of vengeance against Aaron, who is himself far from innocent of ruthless vengeful action. And still, he is no equal to the white courtiers. A mother gives over the daughter of her antagonist to her two sons to be raped as an act of vengeful vindictiveness. After carrying out the rape they cut out her tongue so she could not tell of the deed, and chop off her two hands so she could not write any note with their names. And it gets worse. Yet this play contains one of Shakespeare’s most moving, sympathetic and rhetorical speeches, delivered by Aaron calling for justice for the murder of his child.

Considering the form and content of his theatre, it is interesting that according to one source, Seneca was hailed and praised by the early Roman Catholic Church. This was most ironic since the same church a few centuries later condemned the theatre and vociferously disapproved of it because of plays such as those written by Seneca. That same dramatist, the source says, was converted to Christianity by no less a Christian than Saint Paul himself!

But please… remember Miriam Griffin’s caution.