The Republic of Haiti holds an exceedingly significant place in the Caribbean. This is for different reasons, some recent: it will host Carifesta XII later this month; some historical: its role in Emancipation. But the country has found itself repeatedly in the news over recent years. It has attracted focus for the wrong reasons, including tragedy and natural disasters.

There are several factors contributing to an interest in Haiti as the next Carifesta venue – these are infinite, deep and inexhaustible in terms of art, culture, history, politics and socio-economics. The major focus will be on artistic and cultural matters, but these are all out-thrusts of history and politics.

West Indian sympathies have reached out to Haiti for its willingness to keep Carifesta alive as a newcomer to Caricom, but these sympathies arise even now, for less celebratory reasons. Even now, there are protests, outcry and solidarity coming from many West Indian quarters against the treatment of Haitians by oppressive policies and practises in the Dominican Republic. This response to political, social and human atrocities closely follow the larger reaching out to Haiti because of natural disasters. There was widespread positive support from many Caricom territories following the tragic earthquakes that seemed to further inflict a nation already struggling under economic poverty and internal political challenges.

West Indian sympathies have reached out to Haiti for its willingness to keep Carifesta alive as a newcomer to Caricom, but these sympathies arise even now, for less celebratory reasons. Even now, there are protests, outcry and solidarity coming from many West Indian quarters against the treatment of Haitians by oppressive policies and practises in the Dominican Republic. This response to political, social and human atrocities closely follow the larger reaching out to Haiti because of natural disasters. There was widespread positive support from many Caricom territories following the tragic earthquakes that seemed to further inflict a nation already struggling under economic poverty and internal political challenges.

History has left that nation in contrasting theatrical symbols – the alter-egos of tragedy and celebration. Emancipation from African slavery was commemorated in the Caribbean only a week ago, and Haiti was accorded a position of praise and triumph in many references to Emancipation and liberation. The Republic, and former Monarchy, was hailed as the founder of Caribbean independence.

History has left that nation in contrasting theatrical symbols – the alter-egos of tragedy and celebration. Emancipation from African slavery was commemorated in the Caribbean only a week ago, and Haiti was accorded a position of praise and triumph in many references to Emancipation and liberation. The Republic, and former Monarchy, was hailed as the founder of Caribbean independence.

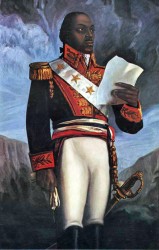

This was because of the already well known achievements. Haiti was the first Caribbean nation to gain independence, breaking from France in 1803. More than that, it had to defy all of the colonial powers, including Spain, England and even the then very young USA, as well as France, to do so. The Haitian Revolution famously led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, was the only fully successful slave revolt, and the only one that did not only abolish slavery, but founded a new independent state. Those triumphs are richer because they were accomplished entirely by inexperienced enslaved Africans.

Yet, that history itself seemed to have been followed by a curse, starting with Toussaint’s successors. Those were the revolutionary and Eurocentric Jean Jacques Dessalines who declared himself Emperor, and the conservative and Eurocentric Henri Christophe who appointed himself King. Their legacy included a cycle of despotism and poverty. Among their successors were the father and son presidents-for-life Francois Duvalier alias Papa Doc and Jean Claude Duvalier alias Baby Doc. The father was notorious for his reign of terror executed by the Tonton Macoutes, while his endearing feature is the belief that he was a spiritualist or obeahman.

That was the source of his nickname “Papa Doc”. But whether it was true, or it was a myth concocted to drive fear into and force respect from his subjects, that same heritage of spiritualism has helped to give Haiti an identity and a reputation of cultural power. Perhaps this early declaration of independence and its long history with no colonial power have contributed to the strength of Haiti’s African survival, the artistic uniqueness and cultural traditions for which it is famous.

For the third time in this century, then, Carifesta is being hosted by one of its newest non-English members. Interestingly, both of these, Suriname and Haiti, are known for the colourful cultural roots that they bring to the festival. Suriname’s distinguishing cultural diversity resulted from its history and its settlement. Developing from its Amerindian past, was a Dutch colonial settlement which brought African slavery and the various cultural traditions of those people. This background was further enriched by the settlers from India, China and the former Indonesia. Maronage helped to preserve spiritual traditions and multi-culturalism with communities of Javanese, Saramaccan, Ndjuka and East Indian, all of which were put on show in successive Carifesta performances.

Similar artistic and theatrical exhibitions may be expected in Haiti, given the equal strength of many African-derived spiritual and theatrical traditions, as well as styles of the visual arts. These tend to be somewhat stronger in form, diversity and African vestiges than what may be found in most of the Anglophone Caribbean. Cuba and the (currently villainous) Dominican Republic are as strong as Haiti in this respect.

A major feature of Haitian tourism has been its visual arts. These include the forms of intuitive (formerly known as ‘primitive’) art seen in the paintings. Best known are the crowded canvases, the detailed motifs and the sometimes bright primary colours. The sculptures exhibit intuition and traditions of wood carving associated with African spiritualism. Such trends are similar in the performing arts highly influenced by the African traditions and spiritual beliefs. The influence of Europe has made its mark, not least among the factors being the Roman Catholic rituals and symbolism known across the West Indian islands with a French historical background. Christianity and African religions have formed hybrids, or have influenced each other in very interesting ways.

Voodoo or Vodun in various forms now attract different attitudes. In the past they have been both sacred and feared, now they are tourism products, invoking more curiosity than fear. Voodoo is a religious ritual but a practice viewed with suspicion in the west because it can be employed as a weapon against persons. It is also performed for healing purposes and its ceremonies, conducted by knowledgeable practitioners are private affairs. Today, however, it is possible for command performances to be arranged for those who wish to see them. The same goes for other traditions which are theatrically performed or exercise influence over theatre. Many will go to Haiti looking forward to the enrichment from those traditional elements as was the case in Suriname. Already, the Carifesta programme does not intend to disappoint them as it has included opportunities on the schedule for both performances and field visits.

The Haitian contribution to Caribbean arts and culture goes even further afield. One significant factor is the prominent place claimed by Haitian writing. There are lights other than Edwidge Danticat being generated. Nowhere did this make more of a statement than in the fact that the first Guyana Prize for Literature Caribbean Award for Fiction in 2010 was claimed by a Haitian, Myriam Chancy, for her novel The Loneliness of Angels.

But Haiti has provided unending inspiration for West Indian writers as well. CLR James was moved by the example of Toussaint L’Ouverture to write both the history and the drama The Black Jacobins to highlight the Haitian revolution. The play was produced in London in 1936 and has been on stage repeatedly around the Caribbean for decades.

Derek Walcott has had a career-long interest in the former French territory, as he searched for heroes and heroism in local West Indian history. His probing produced works which he started very early in his career in Jamaica in the 1950s, developed and repeated in later years.

Those plays included Henri Christophe or Wine of the Country during the Jamaica years, followed by Drums and Colours commissioned for the opening of the official headquarters for the short-lived West Indian Federation in 1960. Since that epic drama directed in Port-of-Spain by Noel Vaz, Walcott’s major work on Haiti was The Haitian Earth. That drama was most recently brought back to celebrate both Walcott and Haiti at St Augustine in Trinidad. But the play itself is far from celebratory. It is tragic, taking a very hard look at what the dramatist sees as the tragedy of the country, inflicted upon it by the likes of Dessalines and Christophe. In a number of symbolic ways Walcott suggests the rape of the country.

Very significantly, among those who revere the revolution and its prime movers were persons who took strong objection to Walcott’s treatment. Some of them highlighted this by walking out on the performance of Walcott’s play at St Augustine. It raises questions about many things in the history. James, in calling his play The Black Jacobins, was employing major ironies in his dramatisation of menials in a humorous sub-plot, ordinary foot soldiers in Toussaint’s army, imitating the Jacobins of the French Revolution and taking their names without any understanding of what they were playing at. Walcott in The Haitian Earth obviously felt Dessalines had betrayed Toussaint, the revolution and the Haitian people, to the point where the very people who he claimed to have worked for, but had, instead, raped, cried “no! no more kings! No more kings!” when news came that Christophe had succeeded Dessalines and had been crowned King of Haiti.

Haitian sympathies and inspiration remain very high. Demonstrating this was a play for which very strong ally of Haiti Rawle Gibbons, who directed Black Jacobins in 1976, was joint writer and director of a most-modern and ritualistic improved drama on the UWI campus to celebrate the new alliances formed with Haitian students displaced by the earthquakes. This was a response in theatre that made laughter an effective art out of the Haitian question – an artistic response typical of Gibbons.

More artistic exchanges are therefore anticipated in Port Au Prince, Ptionville, Cap Haitien, San Souci and several other venues when Carifesta XII is staged there from August 21 – 30, 2015.