By Nigel Westmaas

Nigel Westmaas teaches at Hamilton College

The rejection of the old politics was implicit in the election campaign and platform of the APNU +AFC coalition. It was fashioned and agreed upon by a process of give and take, and a sense that Guyana had to emerge from its morass of corruption and misrule through a format of partnership and consensus. Even though the electoral mandate in May 2015 was razor slim, and in spite of its imperfections, the Cummingsburg Accord allowed for a glimmer of possibility for a broad- based inclusive government. For the Cummingsburg Accord to work, however, it must be transformed into a national unity accord- one that rejects the old political culture and politics of racism, assassination, corruption, paramountcy, and the stultifying culture of absolute obedience to the party line. And no matter how difficult the process, this has to be key ingredient of the new government’s political and social mission. Complacency on these and other critical issues is perilous for the country’s future. Guyana has for far too long been in a national slumber on the way forward. Crisis after crisis swarms over the country and we have witnessed administration after administration attempting failed prescription after failed prescription. The old limited forms of engagement just cannot work given the widespread nature of the country’s complications. Just witness a few:

-There is a security crisis in which communities feel under siege from crime and criminals

-There is a security crisis in which communities feel under siege from crime and criminals

-There is a social crisis in domestic violence and suicide

– There is a crisis in the cost of living for ordinary Guyanese.

-There is a crisis in race relations and its alter egos national unity and reconciliation.

-There is a longstanding necessity for constitutional reform (although we see positive signs from the new regime on this front).

The APNU+AFC government has only been in office now for just about three months, so it is inconceivable that critics can come hard at them as a coalition now adjusting to the reins of power and policy formulation. But early indications point in certain directions and not all criticism is invalid. Indeed, social media and public opinion encountered a “viral moment” when it was announced that Ministerial salaries were to be raised. In fact, the people would have imagined (and expected) that a powerful message and example to the public would have been a cut in Minister’s salaries rather than an increase as a way of making a transparent statement in leading the nation in a different moral and political direction in respect of political culture and economic equality for all. Indeed the inspiration of the APNU+AFC campaign and one of its strongest planks was the coalition’s strident denunciation of the high salaries and corruption of the previous regime.

In a society where the poor and the powerless have little to no protection from crime and the high cost of living, it would have been a travesty to raise already high ministerial wages. There were different views on the subject of increased salaries for Ministers from various spokespersons but at the end of the day the government sensibly placed the idea on the back burner.

This is a serious matter, as we well know how one whiff of comfort leads to more and more gratification by those too weak to keep their integrity. That is how corruption begins – with small unaccountable, unchallenged steps. There have also been other missteps – the gender balance of the Boards and cabinet positions is one since ventilated publicly in the media and thankfully there was a frank response by the state to reconsider the composition of the boards.

The APNU+AFC administration and the whole country has commendably came out forcefully in defence of Guyana’s territorial integrity, an issue long settled by the 1899 arbitral award. This in response to Venezuela’s latest salvo against Guyana in the gazetted decree on the “Atlantic coast of Venezuela”. Guyana also took its campaign to CARICOM and the international community. Guyana’s foreign policy should however not be honed to a single trajectory. It would be decent for the government to go on a human rights offensive in the region. For example, Guyana ought to come out and comment strenuously on the racist and discriminatory laws instituted by the Dominican Republic directed against and intended for the mass deportation of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian heritage. Guyana, since independence and with lulls here and there, has shown its commitment to major regional and international issues especially from the 1970s. We can’t afford to ignore issues like discrimination in immigration issues like the one in the Dominican Republic especially as Guyanese travellers and immigrants have faced some of the same evils in the region.

A national response for national unity

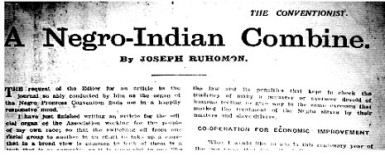

The struggle for multiracial unity or national accord on race relations arguably remains the most crucial element that informs responses to all the other national crises. Ignoring the discomfort of addressing the racial issue, the elephant in the room, will not lead to its obsolescence. All Guyanese know in their daily lives, or are subconsciously aware, that the race or ethnic problem (using these terms interchangeably) is a longer issue that looms as far back as the post emancipation period. And is one that requires more participation, thought, energy and vision than appears to be currently ensconced in the Ministry of Social Cohesion. The title and mission of this ministry – under the leadership of Amna Ally – has already been queried in sections of the press. If we apply the term assigned to this Ministry, than one can suggest that all Ministers and public servants should be tasked with the necessity of “social cohesion” and bring the multiracial message along with their portfolios. All that we have seen so far in the last 50 years and earlier is the eviscerating anxiety and trauma of bad race relations. In 1938 Joseph Ruhoman, the prominent Indian Guyanese activist and intellectual of the period, was invited to pen an article in the Conventionist, the newspaper of the Negro Progress Convention (an organisation established in 1922 to support the cultural and economic development of African Guyanese). Ruhomon articulated “cooperation” between the races. The 1950s with its brief sparks of multiracial unity regressed into the horrible open racial crisis and violence of the early 1960s. The independence and republic periods emerged and now in 2015 we are still beset with the largely the same issues of race and ethnic insecurity and its effects. The new regime obviously cannot solve the race issue on their own or quickly but they are in a good position, as a fresh government, to go to the villages and towns and wards and provide newer perspectives on these difficult issues – trying new things in contrast to efforts that have never worked. The Cuffy250 committee has commenced important social and educational work in the African-Guyanese villages. This is an important step because it is organic work not necessarily connected to party political mobilization and can act as a stimulus against complacency and the dependence of “waiting on the state” in all Guyanese communities, Will there be independent or semi-independent organisations doing comparable work in Indian Guyanese and Amerindian communities? For its part the APNU+AFC administration, with its coalition vison in tow, cannot leave the task of education, economic turnaround and social activism in Indian Guyanese communities to the PPP as this, given the latter’s track record, will only result in electoral and ethnic consolidation.

The struggle for multiracial unity or national accord on race relations arguably remains the most crucial element that informs responses to all the other national crises. Ignoring the discomfort of addressing the racial issue, the elephant in the room, will not lead to its obsolescence. All Guyanese know in their daily lives, or are subconsciously aware, that the race or ethnic problem (using these terms interchangeably) is a longer issue that looms as far back as the post emancipation period. And is one that requires more participation, thought, energy and vision than appears to be currently ensconced in the Ministry of Social Cohesion. The title and mission of this ministry – under the leadership of Amna Ally – has already been queried in sections of the press. If we apply the term assigned to this Ministry, than one can suggest that all Ministers and public servants should be tasked with the necessity of “social cohesion” and bring the multiracial message along with their portfolios. All that we have seen so far in the last 50 years and earlier is the eviscerating anxiety and trauma of bad race relations. In 1938 Joseph Ruhoman, the prominent Indian Guyanese activist and intellectual of the period, was invited to pen an article in the Conventionist, the newspaper of the Negro Progress Convention (an organisation established in 1922 to support the cultural and economic development of African Guyanese). Ruhomon articulated “cooperation” between the races. The 1950s with its brief sparks of multiracial unity regressed into the horrible open racial crisis and violence of the early 1960s. The independence and republic periods emerged and now in 2015 we are still beset with the largely the same issues of race and ethnic insecurity and its effects. The new regime obviously cannot solve the race issue on their own or quickly but they are in a good position, as a fresh government, to go to the villages and towns and wards and provide newer perspectives on these difficult issues – trying new things in contrast to efforts that have never worked. The Cuffy250 committee has commenced important social and educational work in the African-Guyanese villages. This is an important step because it is organic work not necessarily connected to party political mobilization and can act as a stimulus against complacency and the dependence of “waiting on the state” in all Guyanese communities, Will there be independent or semi-independent organisations doing comparable work in Indian Guyanese and Amerindian communities? For its part the APNU+AFC administration, with its coalition vison in tow, cannot leave the task of education, economic turnaround and social activism in Indian Guyanese communities to the PPP as this, given the latter’s track record, will only result in electoral and ethnic consolidation.

Racism and race relations have been an overriding discomfort. Openness on the subject can be fraught with minefields and risks connected with one’s intent. Silence and a silent narrative protecting one’s turf from the marauding ‘other’ has been the leitmotif of our collective response to race and race relations. Evasion of the issue of race until “elections” and then a scramble to formulate an “ethnic” policy to garner support from the “other side” as national elections looms has been the pattern. This approach from “both sides” has been the problem solving design for what seems forever. For the most part it has failed. In a very important article published in 1978, Eusi Kwayana reasoned that Guyana’s race problem was rooted in “ethnic insecurity” and called for a “new system” of response. In support of his point Kwayana wrote,

“Revolution at the level of the political system will not introduce at once ideal race relations. It will not mean everybody at once loving everybody. It will begin the process leading towards the ideal by taking the most irritating factor, races, out of political exchange. Only in such circumstances can any genuine revolution proceed. Racial insecurity will remain, at even less intense level, until the masses of people experience the working of the new system and its emphasis on the security and dignity of the masses of the working people and of the whole nation…”

As a response to the host of problems the country faces – more properly defined as a national crisis – we actually need compassionate Ministers open to criticism and available to the public. State officials from the President down cannot present themselves in the old colonial fashion of only visibly pandering to diplomats and outsiders but must prioritize the immense prize within – the Guyanese people and especially the Guyanese working people who have suffered so long. The late great trade unionist and nationalist Hubert Critchlow would expect no less than Guyanese development built on the material basis of and struggle of labour before and after independence.

Next year the country will celebrate its 50th anniversary as an independent nation. The celebrations next year should not only be an occasion for backslapping and self-congratulations and fireworks, but a time to think through and offer even more creative solutions to issues like race and other social divisions. In other terms, the opportunity of our 50th anniversary should be used to involve a forthright national discussion on what we did right and wrong as a nation and how well we are prepared for the next fifty.