Dear Editor,

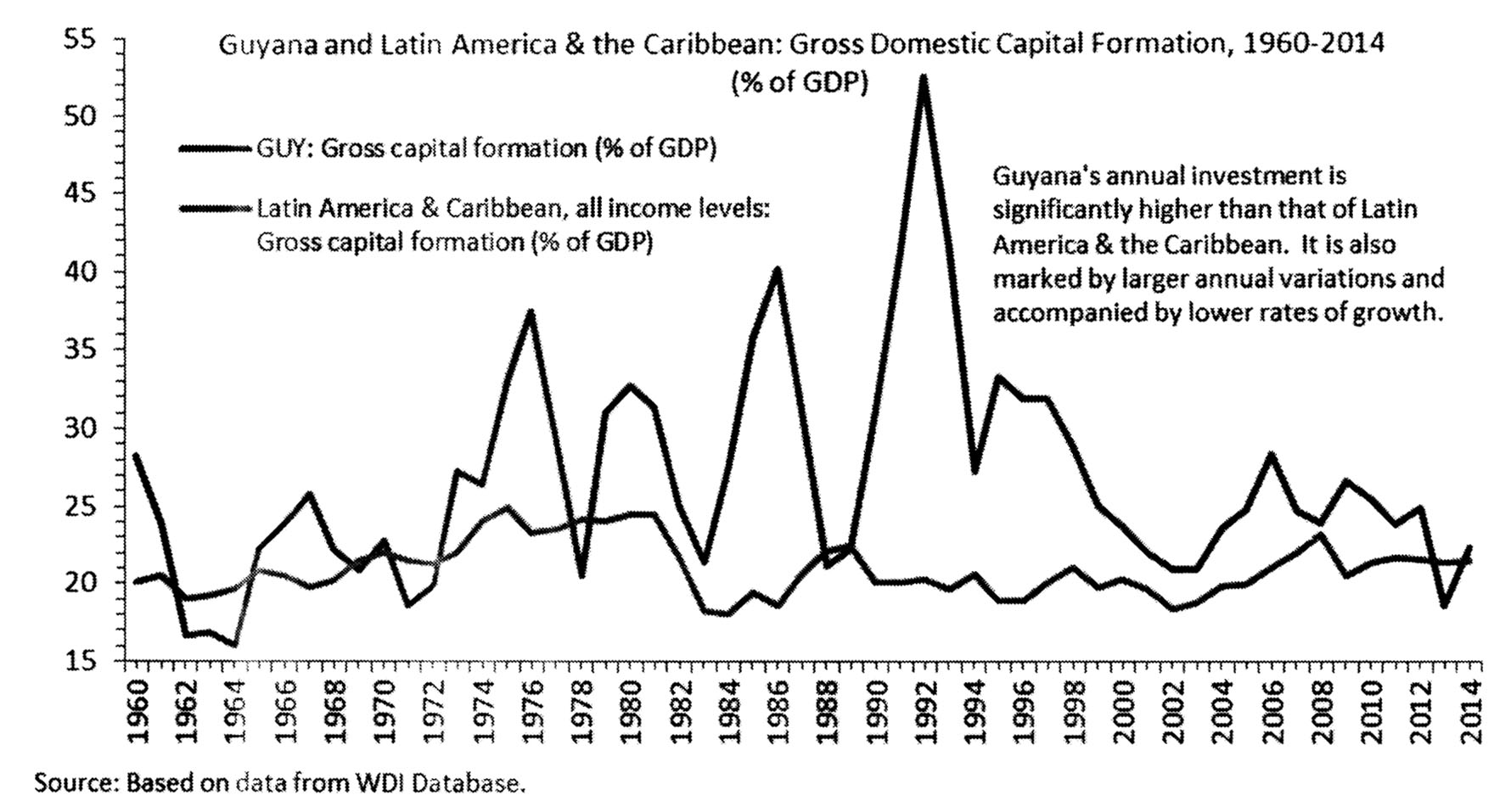

Investment is another issue I left dangling in my SN letter of 18 August. It is remarkable how high a share of its GDP Guyana has been investing during the last several decades. During the forty-five years from 1960 to 2014, Guyana invested an annual average of 26.7 per cent of its GDP compared to a significantly lower share by Trinidad (23 per cent), and Latin America and the Caribbean (21 per cent). Developing East Asia and the Pacific channelled an annual average of 33.2 per cent of its GDP to investment (see accompanying chart).

Despite this high level of investment, Guyana’s economy grew by a pathetic 1.9 per cent during the forty-five year period; that of Latin America and the Caribbean, by 3.8 per cent; and that of East Asia and the Pacific, by 7.3 per cent. There is wide agreement that capital accumulation is an engine of economic growth, and that economic growth is higher in countries with a relatively higher investment-to-GDP ratio. Then why was growth so puny in Guyana?

First, it is usual for the volume of investment and growth to move together in the same direction. But analytically, the interest is whether a change in investment leads to a change in growth. Visual inspection of Guyana’s data reveals that there are times when an increase in investment is associated with either a positive or negative growth, and when a decline in investment is associated with either a positive or negative growth. It is thus difficult to ascertain whether changes in year-to-year investment boost or hinders growth.

If it is difficult to tell whether investment this year yields a return immediately, could its effect be delayed; that is, investment this year will not bear fruit until next year? Because it takes time to build fixed capital, such as drainage and irrigation systems, roads, machinery and equipment, it is plausible that the growth effect of investment is delayed until next year (in the jargon: lagged by one period or more, depending upon the kind of investment). But visual inspection of the presumed delayed effect of investment on growth shows the same pattern as when the effect is assumed to happen without delay.

Is there a way out of the investment-growth conundrum? There is. One way is to look at the correlation between the two series. The result shows that changes in investment and growth are correlated, but the association is extremely weak (0.06); it is much stronger in Latin America and the Caribbean (0.57), and East Asia and the Pacific (0.77).

Ok, correlation is not causation. A better way to unbundle the relationship between changes in investment and growth is to employ a more sophisticated econometric technique known as Granger Causality, which determines whether or not one variable causes another. The most plausible results indicate that a change in investment this year and last year causes current growth. In other words, an increase or a decline in the volume of investment in Guyana (as elsewhere) drives economic growth up or down. By how much? It is difficult to say anything without further analysis. However, a quick regression shows that a 10 per cent increase in investment in Guyana causes growth to rise by 0.5 per cent. Different categories of investment have different effects on growth. For example, an extra 1 per cent of GDP invested in machinery and equipment increases GDP growth by one third of a percentage point. Foreign direct investment, private investment and public investment all have different impacts upon growth.

Second, growth in Guyana requires heavy investment in infrastructure to expand productive capacity; significantly more investment per unit of output in Guyana than in many other developing countries. The main reason for this lies in the topography of the land, especially the coastal areas where the bulk of agricultural activities are located. But poor construction, poorer maintenance, and corruption depreciate physical capital – roads, drainage and irrigation canals, bridges, sea defences, machinery, etc – faster than normal. The result is that the installed infrastructure functions way below capacity. In other words, a fair portion of Guyana’s investment is wasted and most of the wastage occurs with respect to public investment. Since 2009, private and public investment have been almost of the same magnitude, about 14 per cent of GDP.

Second, growth in Guyana requires heavy investment in infrastructure to expand productive capacity; significantly more investment per unit of output in Guyana than in many other developing countries. The main reason for this lies in the topography of the land, especially the coastal areas where the bulk of agricultural activities are located. But poor construction, poorer maintenance, and corruption depreciate physical capital – roads, drainage and irrigation canals, bridges, sea defences, machinery, etc – faster than normal. The result is that the installed infrastructure functions way below capacity. In other words, a fair portion of Guyana’s investment is wasted and most of the wastage occurs with respect to public investment. Since 2009, private and public investment have been almost of the same magnitude, about 14 per cent of GDP.

Third, there is the important issue of the extremely low productivity of capital in Guyana. This is as demonstrated by negative values for the gross incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR) for the economy as a whole, which ranges from very high negative to low positive values: from negative 28.7 in 1977 to positive 0.90 in 1974. Similarly, the marginal efficiency of capital (MEK) ranges from low negative to low positive values: from negative 0.73 in 1982 to positive 1.53 in 2006. Between forty-four years from 1961 and 2014, both the ICOR and MEK were negative thirteen times. The poor return to capital is also reflected in the lack of demand for investible funds and the abundance of excess liquidity in the system. Data does not exist for the calculation of sectoral ICORs, but it is likely that capital is far more productive in the mining and industrial sectors than in the agricultural sector, and in the private than public sector.

The annual ICOR series are marked by extreme variability. Negative values indicate the creation of unused capacity and low positive values indicate that capacity is being used faster than it is being created. The peculiarity of the ICOR and the associated low MEK are related to the very nature of the economy: deeply open (ie, a very high trade-to-GDP ratio), meaning that it is highly dependent upon exports and imports, and a narrow export commodity bundle. In a word, the local economy is highly vulnerable to fluctuations in the global economy, which is worsened by domestic factors. The latter includes the reels of red-tape that act as a barrier to starting and doing business, pervasive and rampant corruption, crime, discrimination, the lack of supportive policies, industrial discipline and competencies. Needless to say, these pernicious domestic factors derive from the king of them all: bitter and factitious ethnic politics.

Summing up, investment is a major driver of economic growth. That this is not the case in the land of many waters – early British writers used to call the country the ‘Magnificent Province’ because of its potential ‒ suggests that there is a need to examine critically the state of the nation’s physical infrastructure, to ensure that sufficient resources are available for the maintenance of this infrastructure, to invest strategically in the future, and to create the conditions that will ensure optimal use of investment. A precondition for this is governance with a human, not an ethnic, face; fairly and justly for all Guyanese, regardless of race, class, religion or other markers.

Yours faithfully,

Ramesh Gampat