Introduction

In last week’s column, I began my response to a question that I have been asked repeatedly in recent times: that is, whether I believe the Sustainable Development Goals, (SDGs), which are slated to be adopted at the United Nations Summit later this month as an integral element of its Post-2015 Development Agenda, offer a sound and adequate planning framework for Caricom and Guyana’s long-term development over its projected life, 2015-30? As stated in that column, my response to this query has always been a resounding yes. This positive response is based on two major considerations. The first is that, the development framework of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs 2000-2015), which preceded the SDGs (that will come into force at the end of this year) was, by any reasonable measure, a considerable success for the region. And, the second consideration is predicated on the current impasses, which are constraining the long-term development of the region (including Guyana).

Significantly, earlier in the week (September 14) the local media carried a feature released by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (UNECLAC) highlighting the region’s striking successes in the attainment of the MDGs, 2000-2015. That feature provided summary information on the region’s performance for each MDG. I strongly recommend this feature to interested readers.

Growth and national savings

Because of this recent UNECLAC feature release, today’s column will focus primarily on continuing my elaboration of the second consideration indicated above. Readers would recall that, in this regard, I had stressed last week the impact of two fundamental development constraints which are facing the region (and Guyana). The first has been the long-term trajectory (over five decades) of low economic growth. And, the second has been the lower than other developing regions’ average rate of national savings, which the region and Guyana have experienced during the decade of the 2000s. This has led to a high dependence on foreign savings, and therefore, all the risks arising from this circumstance. Thus for the region as a whole, foreign direct capital inflows (FDI) had peaked at US$6.5 billion in 2008, and by 2013, as a result of the global financial collapse (The Great Recession), it fell to only US$1.2 billion, or 80 per cent less. As the former United Nations statistician (Ramesh Gampat) has recently reminded us in the Stabroek News letter columns, between 1960 and 2014 Guyana’s economic growth was somewhat lower than 2 per cent per annum. This has meant that, using 2005 prices as the base year, Guyana’s GDP did not even double over this long period; indeed, it rose from US$770 million in 1960 to only US$1,381 million by 2014.

More strikingly, it is clear that the region’s economy has been particularly stalled since the start of the Great Recession in 2008. This has been largely the case for its tourism-dependent economies. Thus, for example, last year’s economic growth in Barbados has been negative (minus 0.3 per cent) and in Jamaica, quite anaemic (1.4 per cent).

Transformation

As I have stressed before, the SDGs as they are presently constructed, focus on several policies and programmes which are quite central to the successful long-term transformation of the region (including Guyana). These are firstly, their focus on structural change and the transitioning of economies out of their present narrow undiversified overspecialization that so typifies the region’s productive sector. Secondly, the SDGs focus on competitiveness. This is an absolutely essential requirement if the region is to participate in the global economy on the basis of a sound regional platform. Thirdly, the region’s (and Guyana’s) low long run economic growth has, regrettably, demonstrated intrinsic tendencies to promote and foster inequalities at all levels ‒ personal, income, wealth, locational, (especially between city and rural areas, and in Guyana, coastal and hinterland areas as well); social groups (classes, race, and gender).

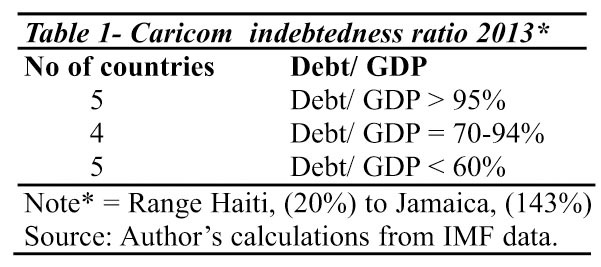

Fourthly, readers need to recall that there remain at present soon-to-expire MDGs that have not been fully attained. The SDGs therefore offer the region an opportunity to complete the unfinished goals and targets set by the MDGs. Fifthly, the extremely high public indebtedness of the region’s economies and its restriction on economic growth, is well known. The data in Table 1 show that, in 2013 five of the 14 listed Caricom member states had a reported debt to GDP ratio of 95 per cent and more. Four member states had debt/GDP ratios between 70-94 per cent. Five of the member states had a debt/GDP ratio of less than 60 per cent. The range of these ratios across the region remains very wide, from 20 per cent in Haiti, to as much as 143 per cent in Jamaica (2014).

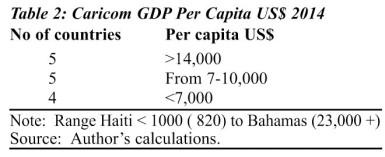

At this point it is worth observing that the level of per capita GDP across the region’s member states is equally varied. Thus Table 2 reveals that five member states had a per capita GDP greater than US$14,000 in 2014. Similarly, five had a per capita GDP ranging from US$7,000 to US$10,000 in that year. And, four had per capita GDP of less than US$7,000. The range shown in the dataset is very wide, from less than US$1,000 in Haiti (US$820) to the Bahamas, greater than US$23,000.

Next week I shall continue the discussion from this observation.