Dear Editor,

Suppose net migration, and hence remittances, was zero over the past several years. How would this have affected the Guyanese economy? This letter is an exploratory attempt to provide an answer.

To do this, I make three assumptions. First, zero net migration, which simply means that in- and out-migration cancel each other out, or, more strictly, a closed population. Second, those who migrated and settled overseas would have to be added to the population, since by assumption they never went abroad. Here I assume, quite reasonably, that the death rate of migrants added back to the population is the same as that for the country as a whole. Third, that the birth rate would have been unchanged for the assumed closed population. In addition, I use data published by the World Bank, the US Department of Justice, the US Department of Homeland Security, the Government of Canada, Baksh (1977), and Index Nundi. I assume that these data are accurate, which is most likely an unreasonable assumption.

These assumptions result in a significant underestimation of net migration. Thus, my data show that a total of 432,167 Guyanese left to settle permanently abroad during 1960 to 2014, which seems low. According to the Caribbean Graphic (September 16), President David Granger told a gathering of Guyanese in Toronto that Guyana could be found on two continents, because “25% of us live in South America while the other 75% live in North America.” Newnow.gy (September 18) estimates that 365,000 Guyanese live in Canada. Also excluded from my data are the thousands of Guyanese living illegally in North America, and those living – legally or illegally ‒ in Europe, Brazil, Venezuela, Suriname, Trinidad, Barbados, and other Caribbean countries. Underestimation of net migration biases steeply upward my estimate of income per person in the absence of migration.

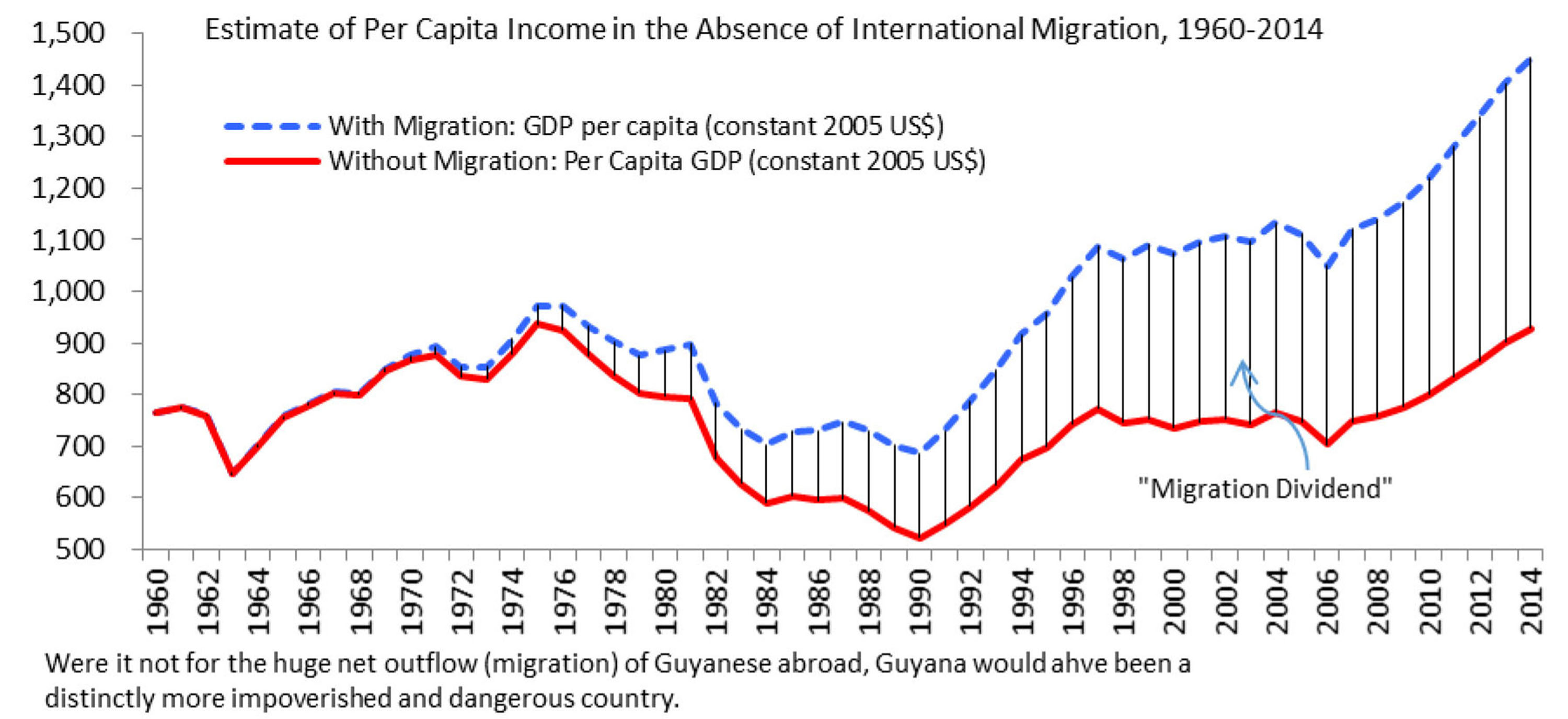

Now consider the estimate (chart). The net outflow of Guyanese abroad really began in the early 1960s following civil disturbances, including strikes, that led to a large number of deaths and grave injuries, huge loss of property (to fire, looting, and robbing), and losses due to closure of businesses. It was during this period, too, that a capital flight began – people follow their money. Income per person in 1960 (constant 2005 US dollar) was $764 but rose to $1,452 in 2014. This represents an increase of 90 per cent in 55 years. If net migration were zero, the corresponding figures are $764 and US$928, which amounts to an increase of just 25 per cent. In other words, if the country’s borders were closed and people did not venture to greener pastures, per capita income would have been $525 lower last year than it actually was. The estimate also shows a growing per capita income gap between a population subject to migration and one bereft of this safety valve. Migration, in other words, is good for growth of income per person. See accompanying chart, which traces income per person for a population with and without migration.

So what does this all mean? Guyana would have been a distinctly poorer and more dangerous country. Income of the average Guyanese in 2014 would have been only twice that of Haiti, instead of three times as big as it actually was. Second, poverty would have been far higher than it actually is today. Data on poverty in Guyana is as scarce and as guarded as plutonium. Nevertheless, the available data reveal that 43.2 per cent of the country’s population lived in poverty in 1992, but this figure dropped to 36.4 per cent in 1999, and was just a smidgen lower in 2006 (35 per cent).

Next, consider the international poverty lines of $1.25 and $2 a day in 2005 prices, converted to local currency using the

purchasing power parity conversion factors. In 1992, 7 per cent of the Guyanese population lived on less than $1.25 per day, while 17 per cent did so on less than $2.00 a day. These figures rose to 9 and 18 per cent, respectively, in 1998. Data for later years are not available. Without migration, these figures would have higher.

But if poverty remains stubbornly high in Guyana today, it would have been significantly higher without the benefit of migration and remittances. It is likely, too, that violence, crime, corruption, suicide, human trafficking and smuggling would have been higher as well. Guyana would have been a considerably more impoverished, illiterate and less connected to the rest of the world via the worldwide web. In addition, the income and wealth gaps between the rich and poor (inequality) would have been wider. Even in its present configuration, the latest IMF report on Guyana argues for greater equity: “On growth and poverty reduction, staff recommended modernizing traditional sectors and further diversifying the economy to spread the benefits of growth across the wider population, particularly those living in underprivileged areas in extreme poverty.”

One other conclusion may be drawn from the data. It is that the PPP benefited tremendously from the lucky remittances boom, which began in 2002 (although I am not sure why). The sustained windfall was a blessing from Marx and Lenin after the stream ran out from the Hoyte-Greenidge negotiated ERP. Without remittances and assuming that all other things remain unchanged, mean growth of the economy during 2002-2014 would have been minus 3 per cent. For the entire PPP regime (1992-2014), average growth would have been an imperceptible 0.20 per cent compared to 2.7 per cent with migration and remittances. On the other hand, mean growth was 1.11 per cent during the 28 years of the PNC. So without migration and remittances, the last half a century from 1964 to 2014 would have been a remarkable period of stagnation when the economy would have expanded by just about 0.7 per cent per annum. Perhaps the situation might have been marginally better because some the people (migrants) added to the population would have produced marketable goods and services.

Yours faithfully,

Ramesh Gampat