Dear Editor,

I thank Mr Rajendra Rampersaud for his letter (SN, September 24), which endeavoured to add nuances to mine (SN, September 15). His main argument for the poor performance of the economy “is that Total Factor Productivity (TFP) has been marginal or negative most of the time. It is also possible for economic growth to be negative despite high investment due to negative TFP impact.” This letter argues that TFP is not a deep, fundamental, explanation of growth; it is a derived but convenient explanation. To understand why, it is merely necessary to ask if TFP is a major source of growth, then how do we boost it?

First, a short piece on growth theory from the 1950s or so. The Solow growth model is dependent upon continuing improvements in technology for growth. The problem is that it assumes that technical advance is “exogenous;” that is, it is something that happens outside of the model and over which economic agents have no control. So the model explains everything but long-run growth. It also suggests that government policies, or the social or geographical status of a country, play only a very limited role in fostering economic growth. While exciting and elegant, the model did not reflect the messier world that humans inhabit.

To fix this shortcoming, economists extended the model by postulating that the rate of technical progress is not exogenous to a country; instead, it was “endogenous,” something determined within the model, something businesses and governments can influence. For example, government affects technical progress via polices, institutions or investment in nutrition, health and education. Economic agents make conscious decisions about technical progress rather than assuming that it inexplicably arises out of nowhere. The fact that government can influence the rate of technical progress opened the way for the Washington Consensus (WC), or unadulterated free marketism. Policies recommended include those linked to devaluation, reduction of budget deficits, liberalization of prices and interest rates, and privatization. The WC failed and we are back to square one. So while economists have identified numerous factors that supposedly drive growth since the 1950s, none is so robust that it holds over time and place. Perhaps investment has the closest relationship to growth more than any other indicator in the literature, as the mountain of cross-country regressions have demonstrated. Yet no magic bullet has been discovered; growth appears to be a more complex process than can be captured in universal models.

While TFP accounts for a significant part of growth, the issue is how to get it to play an even more important role. But first it is necessary to understand how economists measure the relative contributions of factors of production and TFP to growth. By employing a technique called growth accounting, which decomposes the overall growth in output into growth in factor inputs (capital and labour) and TFP, economists discovered that only a portion of economic growth is explained by the growth of inputs. The unexplained (or Solow residual) portion presumably reflects advances in production technology and processes, which are conventionally attributed to all production factors together, and is referred to as TFP growth. TFP is thus an amorphous entity, but may be taken as a measure of an economy’s long-term technological dynamism.

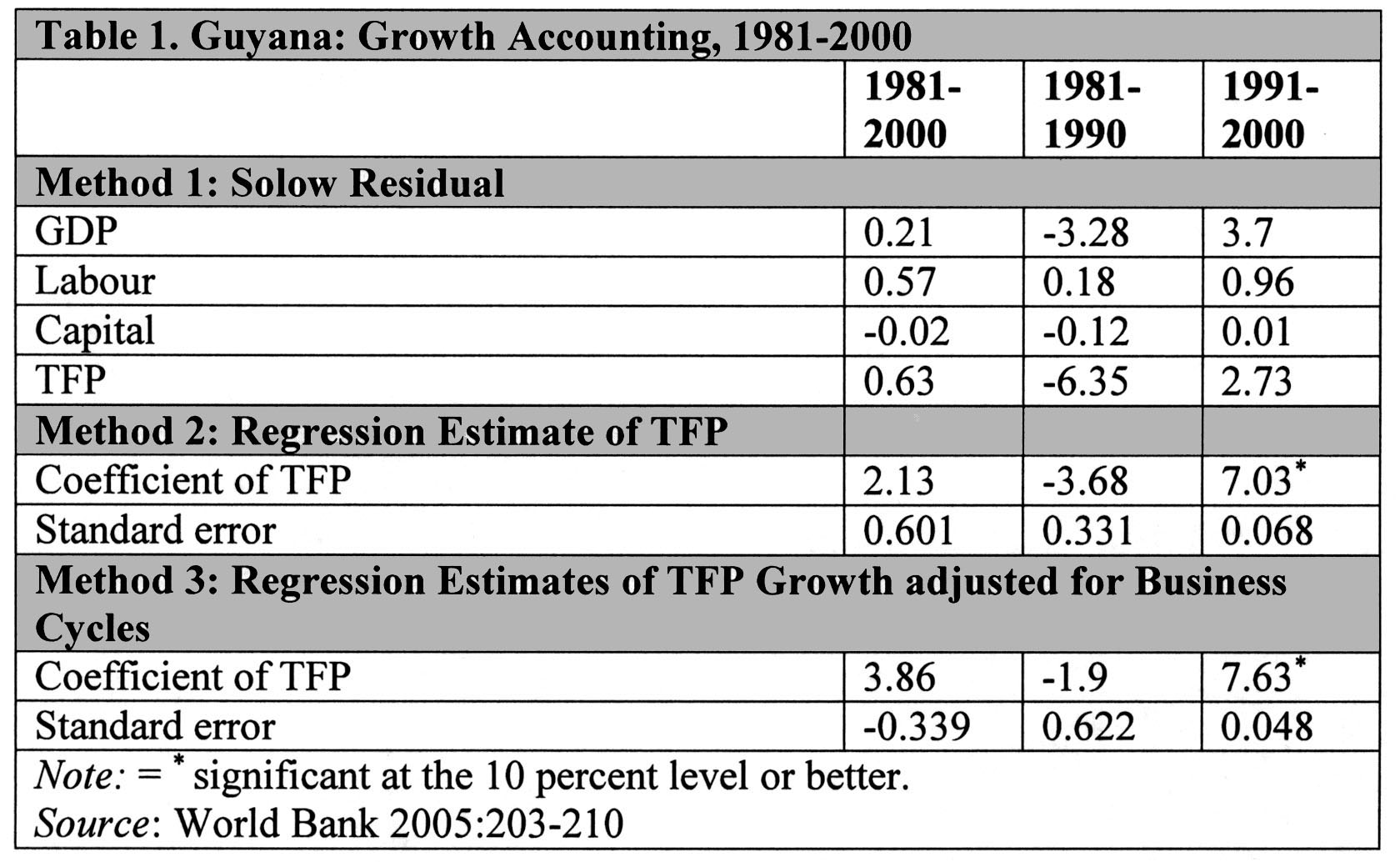

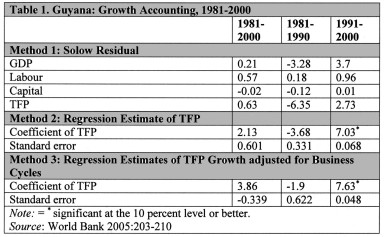

Because the measurement of TFP is fraught with difficulties, at least three different metrics are employed: Solow residuals, regression estimates, cyclical adjustments, each with its strengths and weaknesses. A 2005 study by the World Bank of the Caribbean points to one clear conclusion: a sharp decline in productivity gains between the 1980s and the 1990s, irrespective of methodology. In fact, after adjustments are made for short-run cyclical fluctuations, the contribution of productivity gains to growth in the 1990s becomes negative. In the 1980s, on the other hand, most estimates show a significant contribution of productivity gains to growth. In other words, growth in factor inputs contributed more to economic growth in the 1990s than in the 1980s. In Chapter 16 of my PhD dissertation I noted – from my regression analysis ‒ that technical progress in Guyana is characterized by a downward trend during 1960-1988.

The estimate of the Solow residual for Guyana shows that TFP grew during 1981-2000, declined steeply during 1981-1990 and recovered strongly in 1991-2000. For the longer period both labour and TFP contributed almost equally to growth, while capital exerted a slight drag. TFP was low during the entire period, 1981-2000, largely because the country’s stock of capital has deteriorated and a fair portion non-functional, capital has been built with outdated technology, poor nutrition and health, an educational system that produces functional illiteracy, and the brain drain. If there is one persistent finding, it is that labour is an important contributor to growth. The two regression estimates support this view, but with different magnitudes of the size of TFP (See Table ).

What does all this mean? That Mr Rampersaud is correct only if one forgets that technical change is not a disembodied entity floating in space or descended, like manna, from heaven. Rather, it is an inherent property of investment in physical and human capital; it is embodied in physical and human capital. From this standpoint, investment is the driver of technical change and thus TFP. For Guyana, the World Bank (2007: 49) finds that “in almost all cases, manager’s education is a significant determinant of the total factor productivity, a key ingredient into firm’s competitiveness.” This is also true of nutrition as an input in human capital. Robert Fogel (2002: 26) observes that the “increase in the labour force participation rate made possible by raising the nutrition of the bottom fifth of consuming units above the threshold required for work, by itself, contributed 0.12 per cent to the annual British growth rate between 1800 and 1980.” In a recent paper on TFP in the US, Robert Shakleton (2013) “notes the correlation between TFP growth and improvements in general health and well-being as reflected in changes in life expectancy.”

It seems, then, that the main problem arises from how investment is conceptualized, which Mr Rampersaud apparently views as merely fixed capital, possibly bereft of technology. Gross investment – not allowing for depreciation ‒ includes changes in inventories, physical capital, purposive research and development, and investment in human capital, or in the language of development fashion, expanded human capabilities. Technical advance is embodied in fixed capital, while investment in education, nutrition and health increases the efficiency of human capital and thus boosts technical change and TFP.

Yours faithfully,

Ramesh Gampat