Dear Editor,

The recent letters of Dr Ramesh Gampat (SN, September 15) and Mr Rajendra Rampersaud (SN, September 24) in drawing attention to Guyana’s high investment/low growth puzzle raise important questions of relevance to future development strategy. Unfor-tunately, this useful discussion seems to be descending into a rather sterile back-and-forth about the merits of total factor productivity which threatens to overshadow and obscure the important points of the original discussion (see SN September 29).

Going back to the original puzzle that Dr Gampat posed: How is it that even in the presence of relatively high investment rates Guyana could muster such poor GDP growth as has been experienced over past decades given the expectation supported by economic analysis that investment plays a significant positive role in economic growth? As he shows, in the 55 years from 1960 to 2014, investment averaged 27 per cent of GDP while GDP grew by a paltry 1.9 per cent annually. He shows Guyana’s investment ratio to be higher than that of Trinidad and Tobago or the Latin American and Caribbean average while average growth for those countries was considerably higher (3.8 per cent) than ours.

This goes to the heart of the question, still unresolved after nearly half a century of independence, of what is the appropriate development strategy for Guyana. Ruling out significant measurement error and accepting that it is reasonable to expect investment to provide a significant positive stimulus to production and welfare in the underdeveloped conditions of Guyana, then it’s a fair conclusion that what we have is a problem of the high inefficiency of investment in Guyana in terms of achieving desired development outcomes. Therefore a big part of crafting a development strategy is to understand what impediments to efficient investment have to be overcome and what conditions are necessary for investment to have maximum impact.

This goes to the heart of the question, still unresolved after nearly half a century of independence, of what is the appropriate development strategy for Guyana. Ruling out significant measurement error and accepting that it is reasonable to expect investment to provide a significant positive stimulus to production and welfare in the underdeveloped conditions of Guyana, then it’s a fair conclusion that what we have is a problem of the high inefficiency of investment in Guyana in terms of achieving desired development outcomes. Therefore a big part of crafting a development strategy is to understand what impediments to efficient investment have to be overcome and what conditions are necessary for investment to have maximum impact.

This also involves addressing the composition of investment (touched on by Gampat) and the institutional setting within which the major players will interact and cooperate for development.

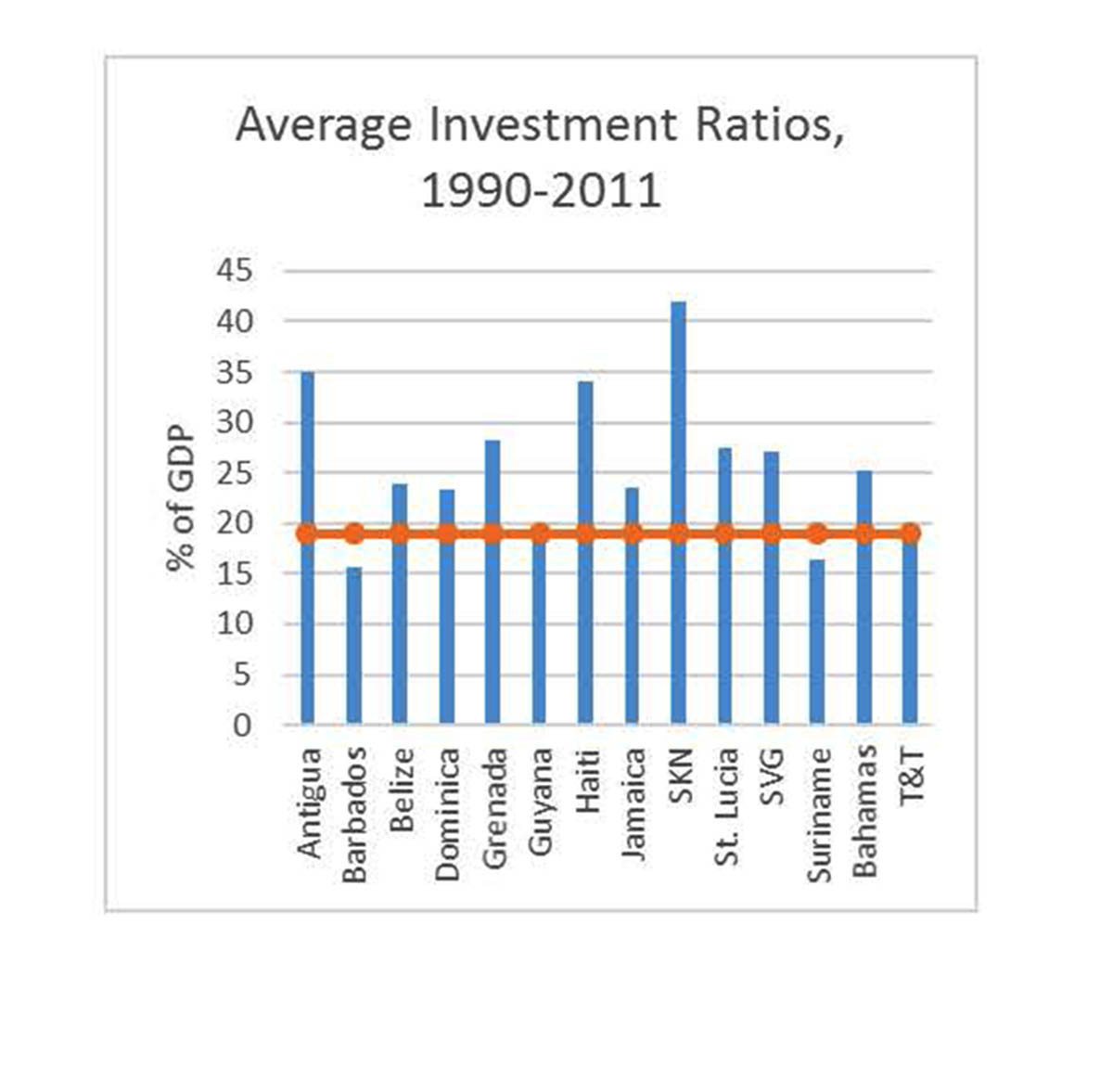

Before giving my take on this issue, it is important to observe that this puzzle is not peculiar to Guyana alone but is in fact a Caribbean-wide phenomenon. As the chart shows, Caribbean countries typically have achieved pretty decent investment ratios, generally above the average for 18 Latin American countries for which data were readily available (indicated by the horizontal line). This chart is reproduced from a presentation I made to a meeting at the UWI in Jamaica in April this year where I highlighted this phenomenon. The value in recognising the regional dimension is to encourage caution in rushing to judgement on the possible underlying causes in the Guyana case. At the same time, we have to be careful not to assume that the same factors uniformly apply to different countries of the Caribbean Region.

Then what explanations can we offer for the evident inefficiency of investment in Guyana? Messrs Gampat and Rampersaud offer some useful suggestions. They acknowledge Guyana’s topography and far-flung communities as an issue calling for high levels of infrastructure spending (sea defence, roads, bridges, drainage and irrigation, etc). It cannot be denied that Guyana’s infrastructure needs impose a heavy burden, but when we consider the virtual collapse of our infrastructure over the decades (roads, electricity, water, etc), it’s hard to say that this is where the high investment money went. Besides, the other Caribbean countries don’t face the same infrastructural challenges as Guyana so one feels that there’s more to the issue. At the same time it has to be recognised that the poor condition of the infrastructure would have been a significant factor holding back development in Guyana.

Rajendra Rampersaud goes on to make a case for technological progress or, as he puts it, “technology with a high level of human capital.” This is an important point, especially in Guyana where for generations there seems to be a belief that our rich endowment of natural resources will be our salvation. When you look at the highly developed countries, there’s little evidence to suggest that their progress depended critically on their own natural resources. It cannot be stressed enough that our most valuable resource, notwithstanding all the gold and bauxite and manganese and timber and now oil and God knows what, is the human resource. It must be nurtured and invested in heavily. But would a heavier injection of investment in human capital be enough to deliver the improved development we need? I doubt it. After all, Caribbean countries can boast a pretty decent record as far as education is concerned, for example, but they still have not achieved high growth.

In general, I support the points made by Messrs Gampat and Rampersaud (with the caveats mentioned), in particular, the important roles of infrastructure, technological progress and human capital investment (bearing in mind that technological progress is as much a product as it is a cause of development). There is however a key element that needs to be added to the discourse, especially in the Guyana context, and that is the institutional setting. This consists in the political, social and legal framework which determines the environment and the rules of the game for the different participants in the process of economic development. Institutional strengthening also has to pay attention to the international setting, doing all that it can to ensure that Guyanese producers and exporters get to participate in the global economy on terms that are favourable. Investment will work more efficiently when different groups in the society are pulling together, confident in the working of institutions to guard their interests and in the existence of channels for their voices to be heard. At the present time this enabling institutional environment is weak and needs strengthening. I would also stress that in Guyana, institutional strengthening has to be built on the foundation of vital constitutional reform. As I have said before, constitutional reform is a top priority in Guyana for strengthening and improving the functioning of the political system (‘The Meaning of Change’ Guyana Chronicle, June 6, 2015).

On the regional level, the low efficiency of investment is an indication that the Region is still caught in a post-colonial time warp, unable to transition to more productive strategies, to find the keys to sounder, more sustained growth in changing international circumstances. Its political, professional, business and other elites appear unable to formulate and execute clear direction and strategies to boost development, leaving the countries teetering in states of chronic pre-crisis with anaemic growth and oppressive fiscal instability. The apparent inability to make serious headway with regard to implementation of the Caricom Single Market and Economy (CSME) is just one example of the general policy paralysis that seems to have gripped the Region.

Yours faithfully,

Desmond Thomas