We have already commented that the ‘summer’ of 2015 was like a field lying fallow in the production of theatre in Guyana. After a fair burst in popular theatre there was quite a retreat.

Some producers explained that this quiet period, which continues up to now, is a reflection of the market forces – it was not a good time for ticket sales, for reasons not plain enough to be articulated here. But it has not been so very quiet behind the scenes and off-stage, and what has been going on there can offer good reasons for the lull. There was Carifesta XII, which occupied quite a few of the major players; additionally, it is now the period which will lead up to the annual National Drama Festival in November 2015 with many groups and companies preparing plays for that.

Some producers explained that this quiet period, which continues up to now, is a reflection of the market forces – it was not a good time for ticket sales, for reasons not plain enough to be articulated here. But it has not been so very quiet behind the scenes and off-stage, and what has been going on there can offer good reasons for the lull. There was Carifesta XII, which occupied quite a few of the major players; additionally, it is now the period which will lead up to the annual National Drama Festival in November 2015 with many groups and companies preparing plays for that.

While public and commercial productions are few, the action behind the curtains is very busy. Several groups, including professional companies, have ex-pressed their intention to enter the NDF with new, current and old plays. Some of them have gone into rehearsals. The National School of Theatre Arts and Drama has just opened for new students, but is very busy outside of the lecture room with workshops, outreach and training for anyone desiring refresher courses or technical boosts in the preparation of their own entries for the Festival. Among the areas being visited are Bartica, Linden, New Amsterdam, Anna Regina, Charity, and other parts of the Essequibo Coast.

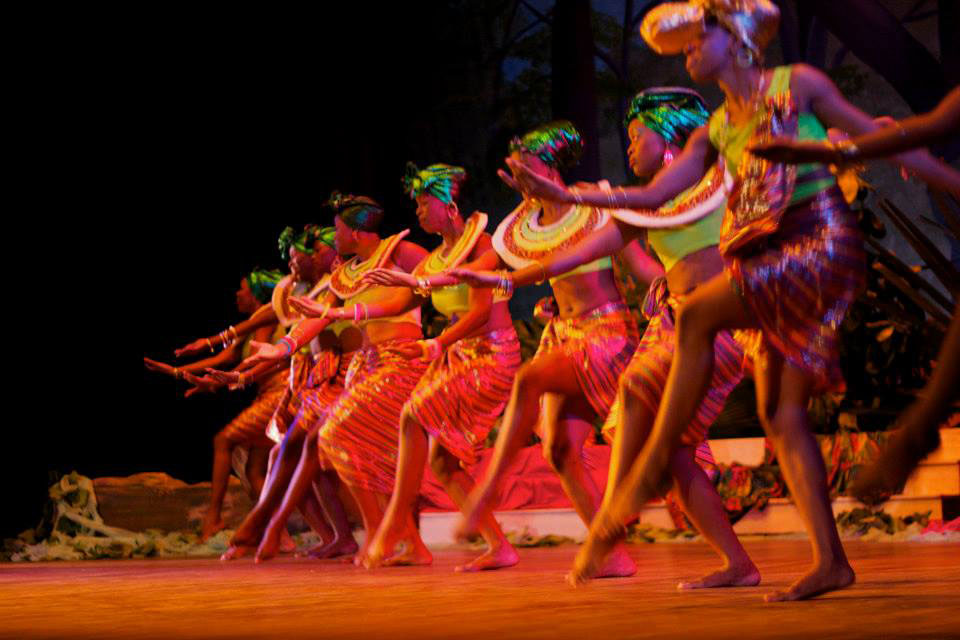

And it is the Season of Dance in Guyana.

And it is the Season of Dance in Guyana.

Tonight at the National Cultural Centre is the second and closing performance of Dance Season 36, the 2015 edition of the annual major production of the National Dance Company. October is the usual time for these performances which do not depend upon market forces or fit into the calendar of popular plays. It is significant that this is “Season” number 36 for the Company since it signals the tradition of full dance theatre productions in Guyana which have their genesis in the 1970s, an important period for the development and professionalising of dance in the country.

The NDC has been at the frontier in national dance theatre reflected in the way it has experimented with these full productions. This, which is its major annual show, demonstrates the work it has been doing for the past year in different forms of dance. It does not seem to consider itself a repertory company and rarely revisits its great choreographies of the past, but instead tries to forge new ways of presenting current preoccupations. The Company’s sense of theatre is always strong as it endeavours to keep the audience in mind in performance.

Cock Fight

In a much different sphere was the production of the popular play Cock Fight by Mike Bartlett produced and directed by Godfrey Naughton. This was the only play on stage during the quiet period and it was interestingly brought back for a second short run. But while this was quite against the grain, the play itself, its type and preoccupations, very well reflected current trends on stage in Guyana.

Everywhere in the Caribbean popular plays tend to dominate in terms of frequency of performances and mass audience appeal. It has been four decades since contemporary comedies (contemporary rather than the classical forms) gained ascendancy across the region, following an explosion in Jamaica, and created a new popular audience for theatre. Many avenues were opened by this, including the local professional theatre. Guyana followed and the trend of popular comic theatre became entrenched.

However, without affecting that trend in any way, another theatrical form gained considerable ground – namely, social realism. While this is by no means a new form, this is how it happened in Guyana. After a lengthy period of comedies and thrillers, many of the leading Guyanese playwrights migrated. At the same time, many new playwrights emerged and many new plays were created largely, but not only, because of training offered by Merundoi, the Theatre Guild, and the National School of Drama. One may add to that, the establishment of the National Drama Festival.

All of these, in combination with individual playwrights acting on their own, resulted in several new plays rising up. Many of them were one-act plays, and many were created for entry into the NDF by amateur groups. But they contributed to a marked tendency for the new plays to focus on social realism. They relentlessly proceeded to tackle burning and problematic social issues. While most were secular, they included church groups entering the NDF dramatising Christian solutions.

Mike Bartlett’s Cock Fight fit neatly into the social realism frame. It was a popular play capitalising on laughter and a drama attempting to address a social theme or issue as well as a psychological condition of individual self-discovery. Yet, its interest in popular appeal overrides everything else about it. It chooses a subject that is a topical social issue, but one that continues to be sensational and to evoke a great deal of laughter – that is, the subject of homosexuality and the fairly new openness and official tolerance of gay couples. Across the world these are serious issues, including the necessity for human rights activism, but on stage in Guyana, they will always be the source of unbridled humour in a society still largely homophobic. Further to that, the play’s interest in popular audience appeal is emphasised in its equally unbridled sexuality, since sex is foregrounded in a way to generate sensational sensual thrills.

Bartlett is a young English playwright, a native of Oxford who now writes for the Finborough Theatre. He has also done radio plays and adaptations. This play Cock Fight, whose original title is Cock, was presented with the “Olivier Award for outstanding achievement in an affiliate theatre” in 2010. It was then brought to Guyana and its title adjusted to satisfy the more conservative public theatre sensitivities in this country.

The plot revolves around a battle between a gay relationship and a heterosexual one in which the hero is fighting to choose between his gay partner with whom he lives and a new-found female girlfriend who seems determined to have him. The hero played by Chris Gopaul, becomes uncertain of his preferences and wavers between his two domineering love interests, threatening the longstanding gay partnership. On the one side is his live-in boyfriend (Michael Ignatius) who dominates and controls him. On the other side is the new girlfriend (Sonia Yarde) who is divorced, a very attractive and sensual individual who attempts equally to dominate what she seems to treat as her new sexual conquest. Ignatius calls in his father (Godfrey Naughton) another strong-willed individual, to strengthen the battle lines on his side.

Gopaul manages quite convincingly to portray the weakness and uncertainty of a man who has not quite found himself. He is constantly inconstant, moving one way and then the other, doing that several times in the play – one may say, a bit too many times. The play works where this tug of war involves a struggling undecided victim in the middle of three strong people all determined to influence him. In the end it is his very lack of will that sees him in the end letting go of the woman and being led by his nose back to his gay partner.

However, as far as acting was concerned, the effect that Gopaul created was fortuitous, since he ap-peared uncertain in places because he was in reality unsure of his lines, his blocking and the dimensions of the stage. He dropped many lines and wandered off into the wrong playing areas of the stage, betraying some lack of concentration or readiness. He was wanting in his limited control of the part.

Sonia Yarde was, on the contrary, strong in what she was required to play. She put in the necessary emphases as she attempted a character who used feminine sexuality as a weapon of war. She used it to overwhelm the new boyfriend she was fighting to keep and to threaten her rival. She even threw it in the face of the father in her attempt to intimidate even him when he intervened on behalf of his son. Yarde put over an extroverted character on a single-minded mission.

The other actors were just as effective. Ignatius showed a cornered man consciously playing a role – he easily assumed victimhood in leading his partner on guilt trips, readily able to switch over to dominance when necessary. Yet he managed subtlety, as there was also a kind of cynicism that he threw at everyone. Naughton did not have as much to do, but convinced in his role as a mediator who was really not impartial.

While Naughton directed the play effectively, in the end it failed to convince. It was really a stretched out, repetitive script with not enough interesting plot or stage business to justify its length. It attempted to load on thrills and sex to entertain its audience with some outrageous dialogue, expletives and explicit terminology. The audience laughed throughout, but it was a play that one could easily get tired of long before its denouement.

The single dramatic situation was prolonged without truly interesting complications. One could even tire of the dialogue, sensational as it tried to be, because of the repetitiousness. If the play wanted to be a serious psychological study it would need development. We needed some convincing explanation of the leading lady’s reasons for her stubborn determination to get this gay man. That gay man’s reason for his sudden change in sexual orientation needed conviction. As was demonstrated in the audience reaction, that the sex was sweet goes for laughter, not serious analysis. Even in the end, making up his mind to stay with his boyfriend was trivial – the boyfriend waved his favourite dish under his nose.

Despite the hilarity, Cock Fight could not stand up to serious scrutiny.