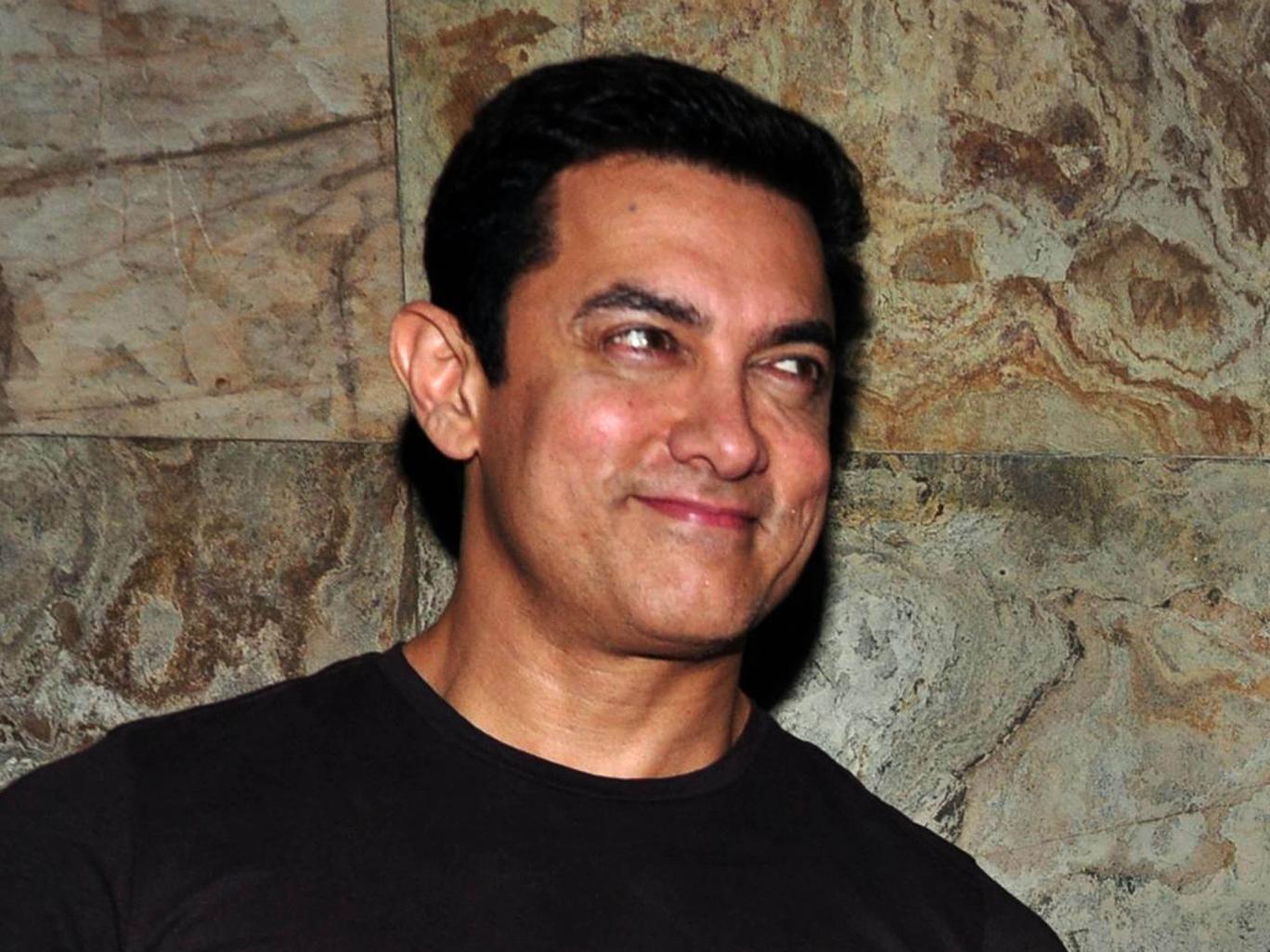

(BBC) The bitter backlash against Bollywood star Amir Khan’s remarks about “growing intolerance” in India tells us a few things about the world’s largest democracy.

At a journalism awards ceremony, Khan said there was a growing sense of fear, insecurity and despondency in the country, and that when he discussed things with his filmmaker wife, Kiran Rao, she wondered whether the family should move out of India.

“It is disastrous and big statement for Kiran to make to me. She fears for her child, what the atmosphere around us will be, she feels scared to open the newspaper every day. There is a growing sense of disquiet, and despondency. You feel depressed, you feel low. Why is this happening?” Khan said.

Many believe Khan was spot on. In drawing-rooms in recent months, friends and acquaintances have told me that they worry about India – the dull economy, shambolic criminal-justice system, unchecked corruption, the fussing about non-issues, and now the acts of intolerance and the coarse and polarised levels of debate – and they would prefer their children to leave. There is a sense that the immense hope that Prime Minister Narendra Modi had offered before sweeping to power last year is fast slipping away.

Many high-profile writers and artists have raised concerns about what they feel is rising religious and cultural intolerance – rationalists have been killed and a Muslim man lynched over suspicions he consumed beef.

Not imploding

To be true, India is certainly not imploding with religious violence. But the protests against intolerance by artists and writers appear not to be so much a reaction to the scale of incidents, but a creeping anxiety over whether the highest levels of the government, including Mr Modi, seriously want to condemn or put their imprimatur behind them.

To make matters worse, Mr Modi and his senior ministers have not been quick enough to speak out against the incidents and hate speech, and when they have eventually done so, they have sounded scripted and remote. Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, for example, famously said that the lynching of the Muslim man would actually hurt India’s image and “amount to policy diversions”.

But the fierce public and social media backlash against Aamir Khan by the ruling BJP and supporters of Mr Modi possibly holds up a mirror to hardened positions in today’s India.

One is the rise of what a commentator calls a “species of hardcore supporters” of Mr Modi, who are derisively called Modi Bhakts – bhakt means worshipper of a deity – by liberal opponents.

They are not the fawning, old-fashioned sycophants that India’s leaders are used to. Their identification with Mr Modi goes beyond mere spirited support, and they defend their leader with a sense of identification and aggressiveness which is unprecedented in India. Some of them behave more like his self-appointed intellectual guardians.

‘Conspiracy’

Many of these supporters also believe that the world is out to get Mr Modi and say people with a history of reservations against him – Khan had condemned the 2002 Gujarat riots – have not been able to reconcile themselves to Mr Modi becoming prime minister.

What accounts for the emergence of the uber supporter? “Maybe, many of us were looking desperately for a strong leader and when we thought we had found one and elected him to power, we lost all perspective,” wonders analyst Pratap Bhanu Mehta.

Secondly, criticising Mr Modi is increasingly being conflated with defaming India.

Junior Home Minister Kiren Rijiju says Khan’s comments on intolerance “only bring down the image of the country and the prime minister”. This, many believe, follows from rising hyper-nationalism and fragile self-esteem.