Each year the elected leaders of Britain’s overseas territories (OTs) gather from around the world to meet with British ministers in London. Their objective is to discuss the continuing partnership with the UK, to establish priorities and to try to resolve differences.

For the most part the issues covered at this year’s December 1-2 Joint Ministerial Council (JMC) while significant, were largely functional and unexceptional, but there were four areas in a Caribbean context where important commitments were made by both sides.

The first was in relation to the vexed question of Britain’s insistence on being able to obtain the details of the beneficial owners of offshore trusts and funds registered in its OTs through the establishment a central public registry. Here, progress was made. Both sides were able to agree, after a discussion described by the Cayman Premier, Alden McLaughlin, as being at times “intense and strained”.

The first was in relation to the vexed question of Britain’s insistence on being able to obtain the details of the beneficial owners of offshore trusts and funds registered in its OTs through the establishment a central public registry. Here, progress was made. Both sides were able to agree, after a discussion described by the Cayman Premier, Alden McLaughlin, as being at times “intense and strained”.

Prior to their arrival in London both he and the Premier of the BVI, Orlando Smith, saw Britain’s prescriptive approach as potentially undermining their robust and well-managed financial services economy. At the meeting however, a “shared understanding” emerged which suggests a new more flexible view by the UK on the provision of such information. What was agreed, in the words of the communiqué, was an approach that will enable the UK’s OTs to hold beneficial ownership information in their respective jurisdictions “via central registers or similarly effective systems.” It was also agreed that in order to make this work, technical discussions were required with UK law enforcement agencies to develop processes enabling the safe and secure exchange of information.

What the declaration suggested was that the OTs, and in particular the Cayman Islands and BVI, have for the time being prevailed against London’s wish to have a central public registry with open public access. Instead, the OTs agreed to have national systems that will be accessible to tax and law enforcement agencies when needed. At the meeting the OTs declined to match the UK’s commitment to make such information public.

Despite this, a reading of the relevant carefully worded part of the communiqué, the statement made to the House of Commons by the UK’s popular new Foreign and Commonwealth Minister for the Overseas Territories, James Duddridge, and conversations with some of the OTs leaders participating, makes clear that what was agreed was a step along a road that Britain sees as leading eventually to a global agreement on public registers of beneficial ownership.

It sees this as the way to tackle tax evasion, aspects of jurisdictional arbitrage, and the use of offshore financial centres for corrupt, criminal or terrorist purposes; thinking that could eventually require that all countries, including Britain, regularly verify and make public, information on beneficial ownership, with the unlikely outcome of the US doing the same for the 0.8 million virtually anonymous companies reportedly registered in Delaware.

A second area of significance to the OTs and potentially to the whole Caribbean region that the meeting discussed was the OTs growing concern about the implications for the relationship should the UK people vote to leave the EU in a referendum to be held sometime in the next two years.

This sensitive political matter ‒ about which there is much more to be written in a Caribbean-wide context ‒ as well as the importance of the ‘strong’ relationship that exists between the EU and the OTs, was acknowledged by the UK. “We agreed to continue to consult in order for the views of Overseas Territories Governments on reform to be taken into account”, the communiqué cautiously noted, referring to the intention of Britain’s Prime Minister, David Cameron, to renegotiate some aspects of the UK ‘s membership in return for recommending staying in the EU.

Another important issue that was discussed that has wider implications was the problem that Caribbean OTs (and others) are having in relation to merchant and commercial banking, money transfer, and their previously unremarkable international relationships with correspondent banks. At the meeting the recent withdrawal of some banking facilities in countries like Cayman and the closure of local branches by international banks, concerned about risk and the cost of compliance with new international financial legislation, was highlighted. In response Britain agreed to “support the Overseas Territories in liaising with UK banks” to ensure that the OTs have full access to banking services. The UK also committed to working together with its OTs to maintain viable banking and financial sectors.

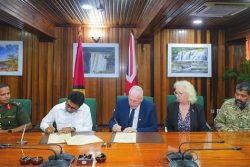

A fourth area of significance was a discussion on the security relationship. Here the communiqué not only made clear the continuing co-operation and commitment the UK has in relation to building capacity and tackling serious organised crime, but also welcomed the commitments in relation to the OTs in the UK’s recent Strategic Defence and Security Review.

This reference to the Defence Review is significant as it is a document that demonstrates the extent to which Overseas Territories form an important part of the UK’s defence posture. While this in part relates to the Falkland Islands, the Review makes clear that “the strategic location of our Overseas Territories” is an aspect of the UK’s special relationship with the United States, described as Britain’s “pre-eminent partner for security, defence, foreign policy and prosperity.” The implication for the rest of the region is that the UK will through its OTs retain a long term role in the Caribbean.

Speaking after the Council to some of the participants, what is apparent is that a higher degree of trust between the UK and its OTs now prevails, despite differences, and much of the dissonance of a few years ago has dissipated. In part this is about issues and personalities, but it also demonstrates that the UK-OTs relationship, as the relatively informal style of the communiqué indicates, is now more about equals, and largely accepts interdependence within advanced constitutions that provide for uniquely local forms of self-government.

Britain’s also seems to have worked out how to encourage the Overseas Territories to endorse its norms, whether they relate to security, financial services or social issues, and has developed a better understanding of the territories unusual, and not well understood mix of god-fearing conservatism, self-confidence, and economic libertarianism.

What was not specifically discussed, despite it being trailed, was where the UK relationship with its OTs will be by 2030 and how this might relate to the rest of the region. According to one OT participant at the working dinner where this was to have been considered, other issues were discussed. It is a pity; this might have been a positive moment to do so.

Previous columns can be found at www.caribbean-council.org