By Clem Seecharran

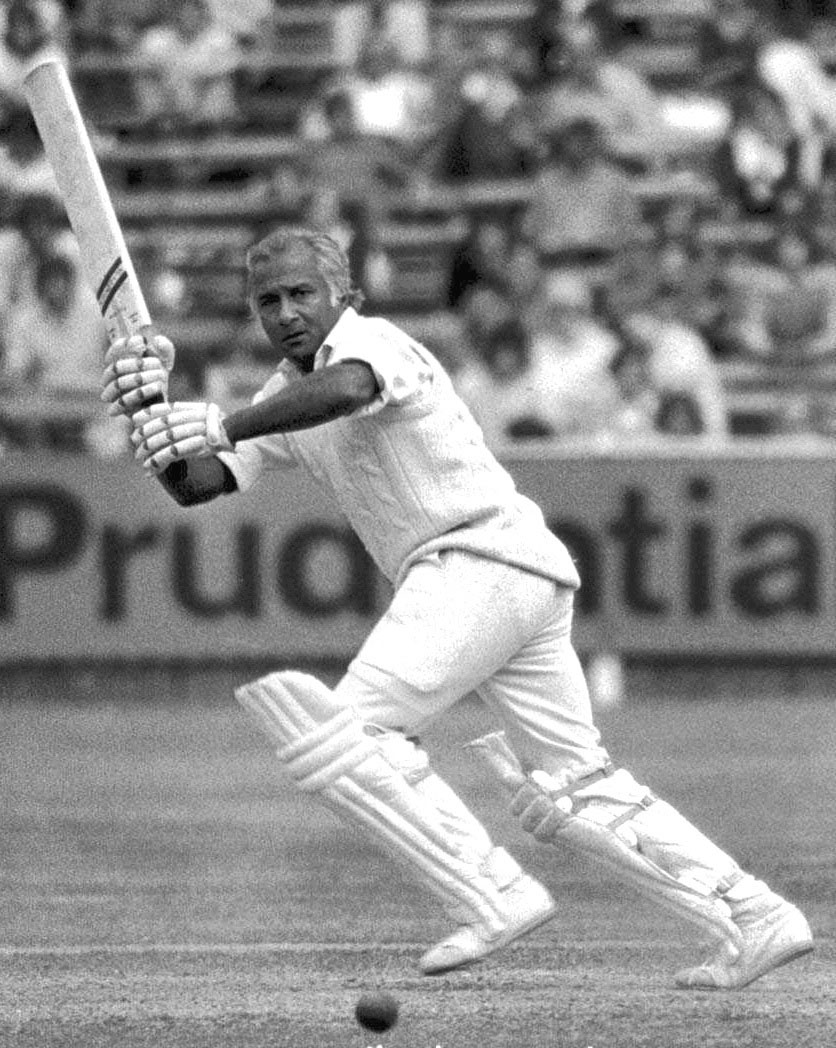

Rohan Bholalall Kanhai will be 80 on 26 December 2015. He was born at Port Mourant, British Guiana (Guyana). He represented the West Indies in 79 Tests between 1957 and 1974, captaining them in his last thirteen. He scored 6,227 runs at an average of 47.53, including 15 centuries and 28 half-centuries. His highest score is 256, at Calcutta in December 1958. He appeared in 61

consecutive Tests between 30 May 1957 and 20 February 1969, when a nagging knee injury forced him to withdraw from the tour of New Zealand. In his first-class career (1955-81), he scored 29,250 runs at an average of 49.40, with 86 centuries and 120 half-centuries. He took 325 catches. But it is the way Rohan scored his runs, the unconquerable flair that has stayed with aging devotees. As he explains in his autobiography of 1966, Blasting for Runs: ‘When I bat my whole make-up urges me to destroy the opposition as quickly as possible and once you are on top to never let up…Once I’ve got the fielders with their tongues hanging out I aim to run them into the ground’.

For Indo-Guyanese, the mastery and international recognition of Rohan Kanhai became central to their identity, fortifying their self-esteem even as their political fortunes slumped from the mid-60s. His perceived genius would be refracted through the political, necessarily an ethnic Guyanese prism. Two men from Plantation Port Mourant – Kanhai and Cheddi Jagan (1918-97), the Marxist Indian political leader – possessed the Indo-Guyanese psyche, pivotal to their self-belief at the end of Empire. Cricket was more than politics by other means for Indo-Guyanese. Kanhai and Jagan were intertwined with Indian religious iconography that bordered on deification. It was Rohan’s bravado that made him the quintessential rebel, an instrument of their resolve as descendants of indentured labourers to erase the ‘coolie’ stain. It paralleled Cheddi Jagan’s radicalism, which sprang from similar promptings, and therefore could also be appropriated in the shaping of Indo-Guyanese identity.

The people of Port Mourant, in a breezy, less malarial district, were healthier and imaginative; this engendered strategies of mobility beyond the plantation. It fed their abiding iconoclasm, as well as their meteoric rise. Reform on the plantation (by the ‘Booker’ leader, Jock Campbell) fed the rebellious spirit with an insatiable appetite for change. And with the suspension of the constitution, six months after Cheddi Jagan’s victory at the 1953 general elections, a