Christmas Bells

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old, familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said;

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men.”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Bells are often associated with the Christmas season. More than that, this association is with peals of joy and merriment, or even the resonant melody of church bells early on Christmas morning heralding the joyous day. Take the sound at the end of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, for instance, when the reformed Ebenezer Scrooge is about to celebrate. We will find that even in this context, there is much more, and bells go deeper than that.

We learn that from the literature, and we have previously observed that the best poems that may be called Christmas poems are not about the joyous celebration of the season. The most enduring works tend most often to use the season either from which to engage other weighty matters plaguing humanity, as an ironic backdrop to the dramatisation of situations of contradictory gloom, or as a way to advance Thomas Hobbesian themes of the brutish brevity of mankind in opposition to the customary spirit and utterances of peace and goodwill.

Prominent among the accustomed texts at Christmas time is the song “Jingle Bells” extolling the merriment carried by the sound and “O what fun it is to ride on a one-horse open sleigh”. Alien as that “dashing through the snow” is to Caribbean climes and culture, it is one of the most popular seasonal songs. But well above the superficiality of the snow is the spirit associated with the Christmas bells. Many other songs and poems talk about these chimes as echoes to the celebratory mood.

Prominent among the accustomed texts at Christmas time is the song “Jingle Bells” extolling the merriment carried by the sound and “O what fun it is to ride on a one-horse open sleigh”. Alien as that “dashing through the snow” is to Caribbean climes and culture, it is one of the most popular seasonal songs. But well above the superficiality of the snow is the spirit associated with the Christmas bells. Many other songs and poems talk about these chimes as echoes to the celebratory mood.

Even literature produced by the Caribbean apply here. The oral literature and songs arising from the Parang of Trinidad are celebratory and ring of revelry. The Parang is a Christmas time cultural and musical form that uses up-beat rollicking rhythm and rhyme to glorify the birth of Christ, and it has strong Roman Catholic influence. But Parang is the only West Indian Christmas time folk tradition that actually celebrates Christmas. The masquerade traditions may be seasonal and partake of the Christmas spirit, but they have a distinct tragic side to them. That is definitely so with Jamaican (as opposed to Bahamian) Jonkunnu, while the St Lucian Papa Jab (Djab) the White Devil (now extinct) sadly laments the loss of goodwill and forgiveness.

What happens in the celebrated texts of western literature? There is a very popularly paraded carol called “I Heard The Bells On Christmas Day” which is taken as typical of the mood of the season. Not only is it regaled as reflecting the happiness carried by the sound of the bells, but as a very significant acceptance of the religious belief. It is Christian – re-emphasising the restoration of faith that the season is supposed to bring. The last stanza is a triumph of the religious spirit and the song rings of the Christian significance of the Christmas bells.

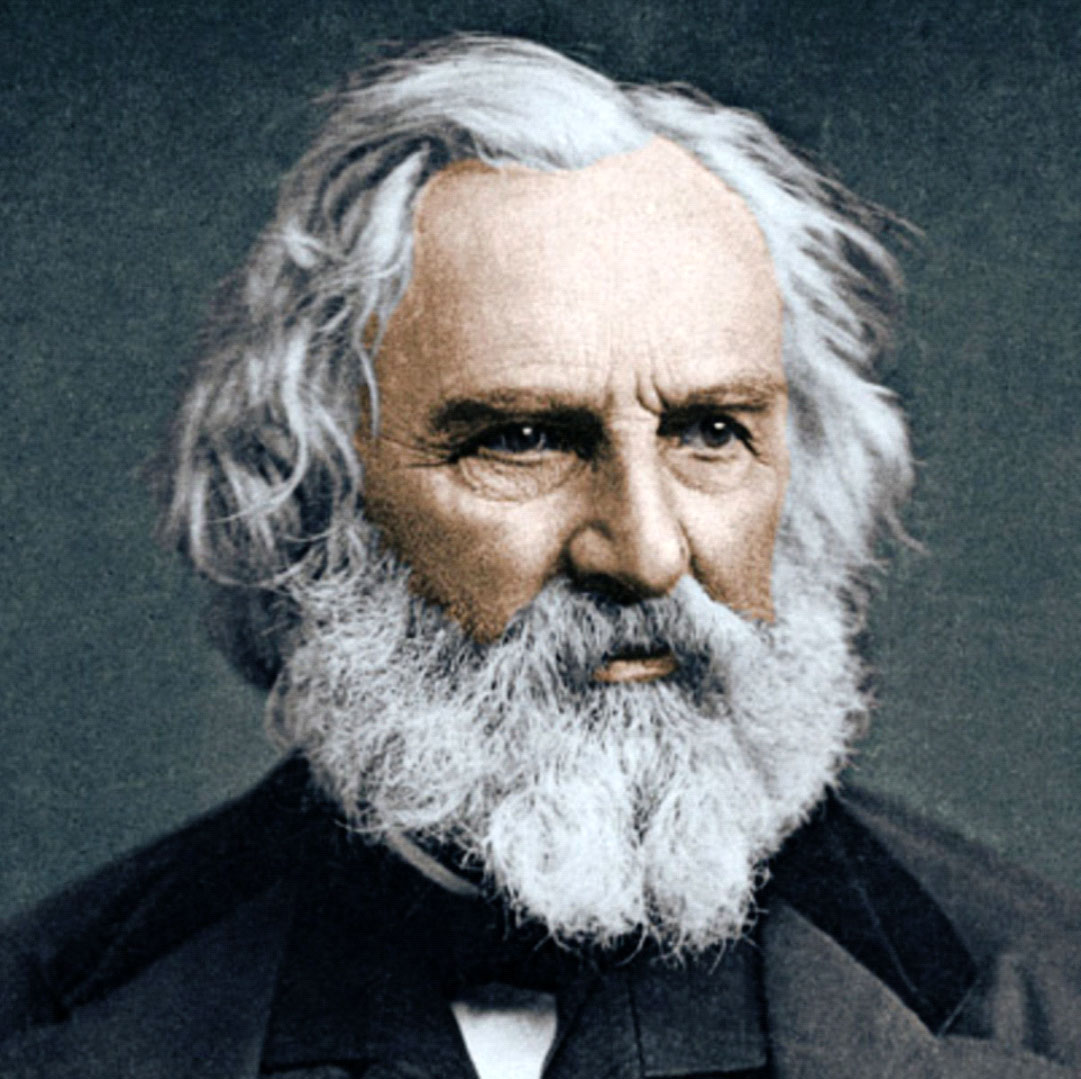

However, that was not the true meaning at the bottom of the poem from which this Christmas carol was made. The carol is really a version of the poem titled “Christmas Bells” (1863) by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807 – 1882) amended and put to music in 1872. The song version removes two of the most important stanzas of the poem that quite speak to what was in the poet’s mind when he wrote it (see stanzas 4 and 5 above).

However, that was not the true meaning at the bottom of the poem from which this Christmas carol was made. The carol is really a version of the poem titled “Christmas Bells” (1863) by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807 – 1882) amended and put to music in 1872. The song version removes two of the most important stanzas of the poem that quite speak to what was in the poet’s mind when he wrote it (see stanzas 4 and 5 above).

Longfellow harboured bitter memories of Christmas and of the American Civil War (1861 – 1865) and wrote the poem on Christmas Day after hearing the church bells. It reflects both personal and national tragedy for him. It refers to the American Civil War, the loss of his wife following a domestic accident and the injury to his son while fighting to defend his nation in the Civil War. The son defied his father to become a Lieutenant in the Union army. Longfellow comments in the poem on the evils of the war and how it contradicts the supposed spirit of peace on earth and goodwill towards men. He took that from the Bible: “Glory to God in the Highest and on earth peace and goodwill towards men” (Luke 2: 14).

Yet listening to the bells he heard the sounds of the cannons “thundering” in the American South as the war told a different message. Although there is some atonement in the final stanza, stanzas 4 and 5 reflect the poet’s bitterness and his strong feelings about the destruction caused by the war. What comes over in the last stanza is a hope that there will be peace in America and real good will can prevail.

Where the use of bells is concerned, Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Bells” (1848/1849) stands out. His first stanza alludes to the types, sound, mood and wintry Christmas atmosphere projected in “Jingle Bells” and its sequel “Jingle Bell Rock”.

Hear the sledges with the bells

Silver bells

What a world of merriment their melody foretells!

How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,

In the icy air of night

But Poe does not remain too long with that theme as bells suggest much more to him that is not quite so happy. While there is great speculation about its meaning, like Longfellow, he hears many other suggestions of deep solemnity in the sound of bells. As the poem continues, the bells get larger, louder and emotionally more complex. They move from “mellow golden bells” of “harmony” and “marriage” to “brazen” and “loud alarum bells” of “terror and “turbulency.”

In the startled ear of night

How they scream out their affright!

Too much horrified to speak

They can only shriek, shriek,

Out of tune.

The “horror” of the bells end in the “tolling” of “iron

bells”.

What a world of solemn thought their monody foretells

How we shiver with affright

At the melancholy menace of their tone!

The sound becomes “a muffled monotone” and what Poe hears is “the moaning and the groaning of the bells”.

Christmas for Dickens conjures up spirits of human suffering, of depravation and of tragic outcomes unless there is a turnaround in the usually stingy mean-spiritedness of mankind. Thomas Hardy looks at the stark, cheerless snow covered landscape and skeletal trees of Christmas and New Year which appear to him as “the century’s corpse outleant”.

Characteristically for writers, humanity is flawed, floundering and out of tune. He is further out of harmony with his usually hostile environment and at war with others and with himself. Christmas is represented as a time of peace, goodwill, forgiveness, great cheer with everyone in harmony. But that state is too seasonal and quite out of sync with what the writers see; so they tend to use Christmas as a forum for dramatising this ironic disparity.