Christmas Bells

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old, familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said;

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men.”

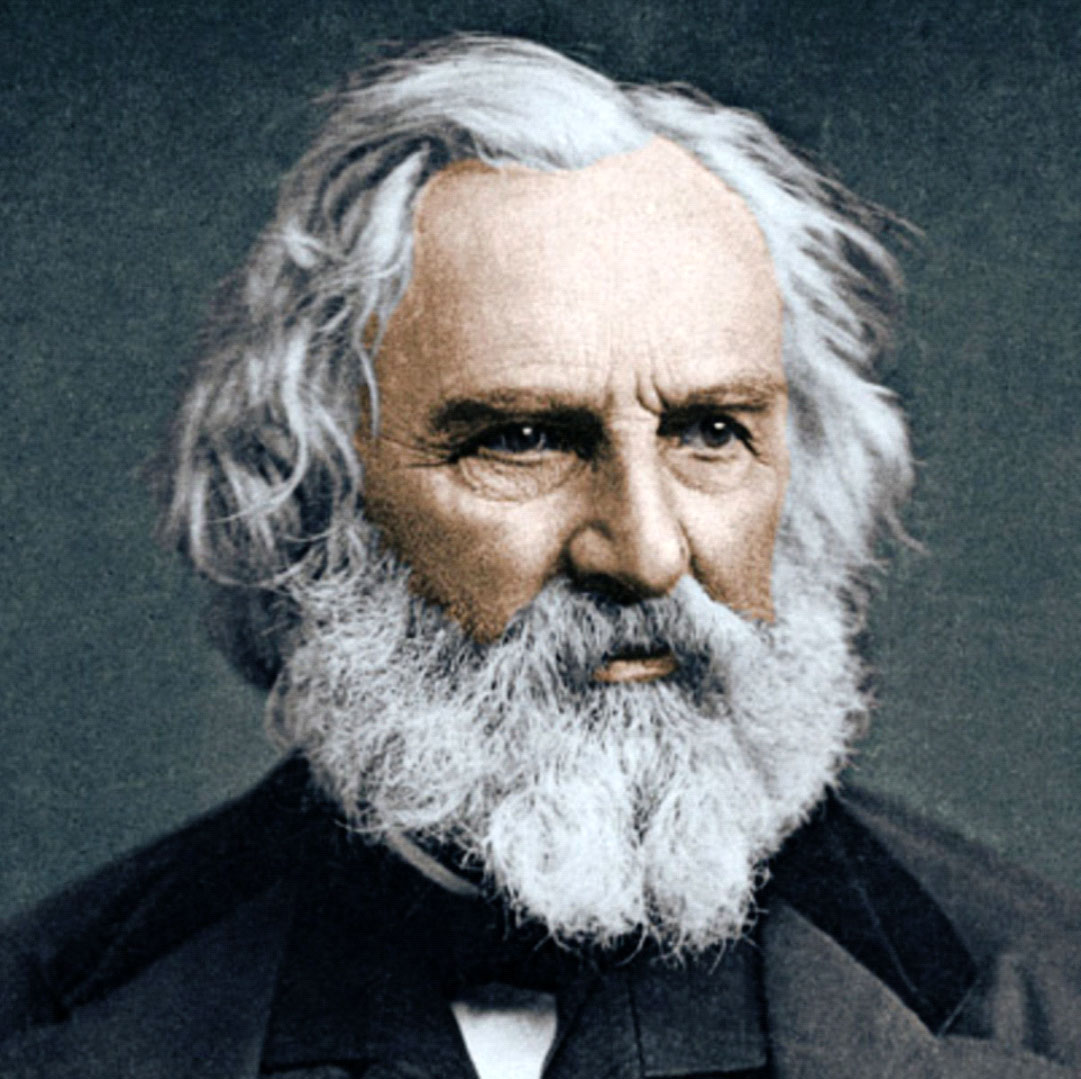

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Bells are often associated with the Christmas season. More than that, this association is with peals of joy and merriment, or even the resonant melody of church bells early on Christmas morning heralding the joyous day. Take the sound at the end of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, for instance, when the reformed Ebenezer Scrooge is about to celebrate. We will find that even in this context, there is much more, and bells go deeper than that.

We learn that from the literature, and we have previously observed that the best poems that may be called Christmas poems are not about the joyous celebration of the season. The most enduring works tend most often to use the season either from which to engage other weighty matters plaguing humanity, as an ironic backdrop to the dramatisation